Walking Tour

Triumph of the Automobile

How Cars Conquered Vancouver

Andrew Farris

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Duke of Conn P25

In the 21st Century our lives, our city, and our civilization have been built around our cars. It's easy then, to forget that they are a relatively recent invention. The first car was seen on Vancouver's rutted roads in 1899, and a mere half century later, by 1950, our society was well on its way to transforming into an all-embracing car culture.

Few people alive today can remember much of this transition, so it might be difficult to understand just how fast and dramatic the rise of automobiles was. For us today, the only comparison can be to the rise of computers. They first began appearing in the 1970s, gained popularity in the 1990s, and in the 2010s practically every job, every business, and every person's social life depends utterly on computers. We can scarcely imagine our lives without them. That is what it must have seemed like for people in the 1950s, looking back 50 years before the car reigned supreme.

In this tour we will learn about the fascinating early history of cars: who invented them and why, how people felt about them, and how they came to conquer Vancouver and much of the world.

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

1. The Car "Fad"

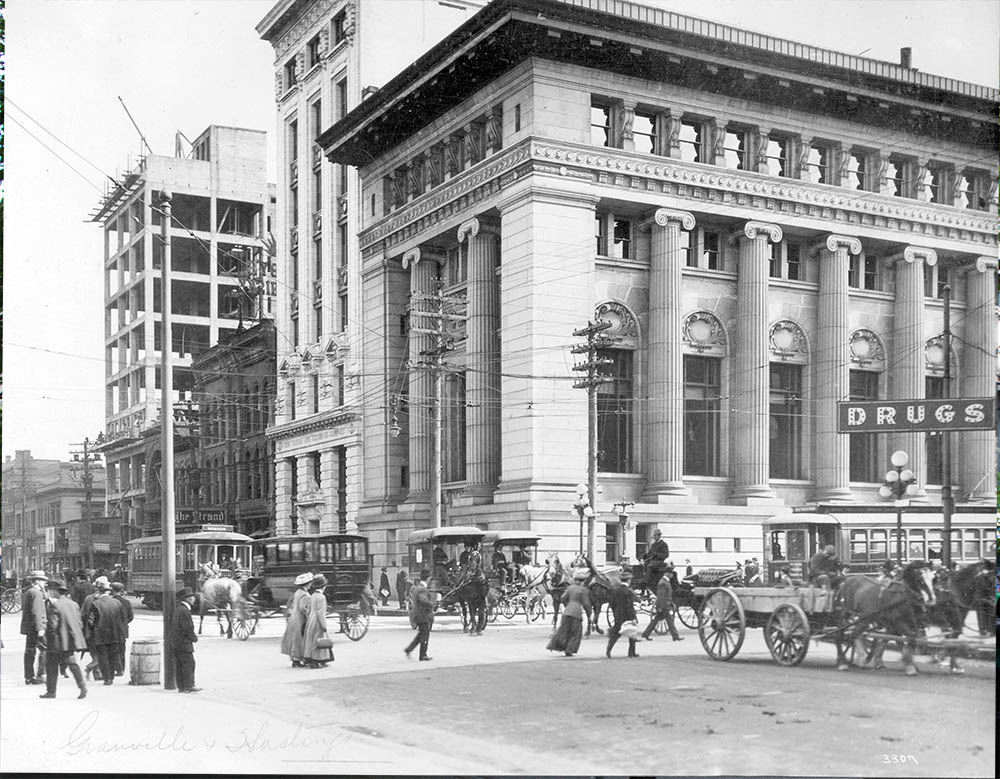

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-1---: M-11-48

1910s

On this busy corner in the commercial heart of Vancouver we can see streetcars, horse-drawn carriages, and wagons. What modern fixture isn't present? There aren't any cars – this would not be the case for long. Cars would conquer the city's roads, transforming the lives of Vancouverites in innumerable ways.

* * *

Given these facts it's hardly surprising that when cars first appeared many people believed they were just a novelty—horses had been the way of doing things forever. The Bookman magazine of New York claimed "Bicycles and automobiles are a fad… [They] will soon disappear, but the love of the horse will never die out of the human heart."2 Many people thought cars were doomed because they needed paved roads. Strange as it may seem to us today, paved roads barely existed a century ago. The acrid exhaust fumes, cacophonous noise, and frequent breakdowns, also counted against cars. Many concluded cars would never replace horses. As you can see, they turned out to be wrong.

2. German Birthplace, French Nursery

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu N419

1899

Commercial wagons are seen here passing in front of the MacKinnon Block, which no longer exists. The modern car was invented in Germany in the 1880s, perfected in France in the 1890s, and first seen on Vancouver's streets only in 1899.

* * *

Benz partnered up with Gottlieb Diamler and started the first car company to try and sell their new-fangled inventions. They later worked with Wilhelm Maybach, the inventor of the motorcycle. They were building on the work of many pioneering Belgian and French engineers, and by 1894 Benz could boast 136 sales of the cutting-edge Model 3.2 Of course at this time nobody had a clear idea of what a car should look like, and the cars the Germans had been developing were more like motorized carriages with bicycle parts—'horseless carriages'.

It is sometimes said that if Germany was the birthplace of the car, France was its nursery. French designers like Rene Panhard and Emile Levassor moved beyond the 'horseless carriage' mentality and laid down a radical new design for their cars. The engine was moved to the front, a water-cooled radiator was introduced, a crankshaft used to drive the pistons, and a clutch and shifter were used to control the transmission. This layout has remained essentially unchanged to this day.

3. Steam, Electricity or Gasoline?

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-3-: CVA 677-659

1900s

Take a look at the carriage on the left of this photo. Though it is horse-drawn it is very similar to the early car designs that tried to put an engine on carriages. At this time of intense innovation nothing about cars set in stone. Nobody knew how a car should look, how it should run, or how it should be used. Many different paths of innovation were followed only to turn be abandoned or turn out to be dead ends.

* * *

Steam actually had the earliest lead, and Vancouver's first car in 1899 was steam-powered.1 Even as late as 1900 many observers thought steam would come out on top. Yet steam cars had drawbacks: they required an enormous amount of fuel, were hard to operate, and on occasion the boilers allegedly blew up with unfortunate consequences for the driver. These explosions were actually extremely rare, but just like how the Hindenburg disaster destroyed the future of zeppelins, a couple of widely circulated and exaggerated tales of exploding boilers destroyed the future of steam cars.

Electric cars were given a go too, promoted by the powerful inventor and businessman Thomas Edison. Electric cars were smooth, silent and easy to operate (unlike their competitors). They were popular in New York and at the turn of the last century hundreds of electric taxis were ferrying people around Manhattan. Their main drawback was that the early batteries ran down very quickly, could weigh as much as 1,600 pounds and would sometimes leak acid. The invention of the electric starter removed the crank that you needed to turn on a gasoline car, making them as easy to use as electric cars. The electric starter, which removed the need for an annoying hand-crank on gas cars, decisively won the battle for the future of the car. By 1914 practically nobody in the world was making steam or electric cars.2

4. Canada's Car Industry

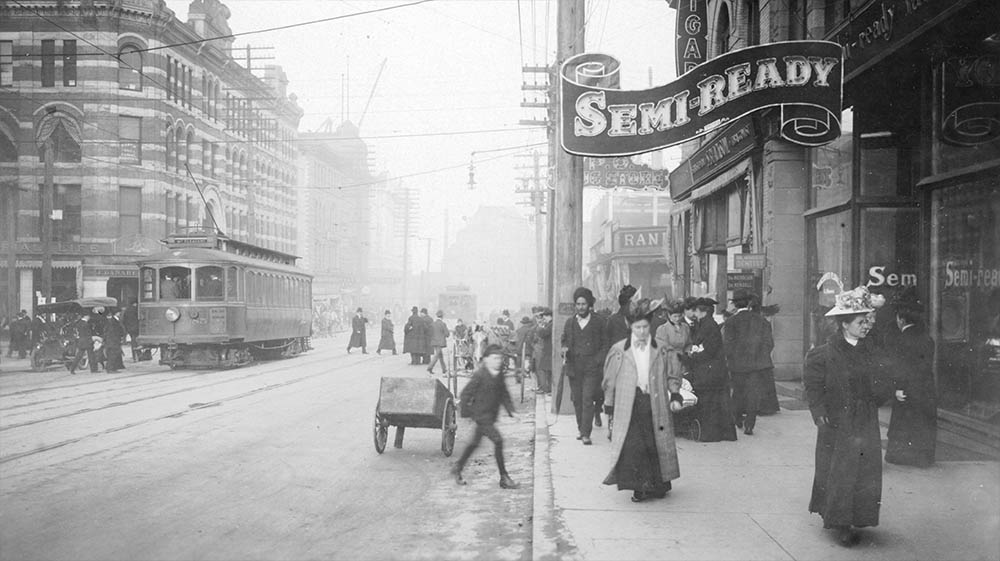

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-3-: CVA 677-529

1906

A busy day on Granville Street. If you zoom in on the photo you can see at the left an early car in Vancouver. After 1900 cars began to appear in Vancouver and across Canada. Canada had many home-grown carmakers who made highly regarded vehicles. Were it not for a few quirks of history, names of Canadian carmakers like McLaughlin and Russell might be household names today just like Ford and Toyota.

* * *

Vancouver's first car was home-made as well, a carriage that was given a steam-engine by the Armstrong and Morrison machine shop. The car, or 'charabanc' as it was called, wasn't a success and later scrapped.

A reporter who took a ride in it certainly liked it enough. He wrote: "The beautiful horseless carriage answered the steering gear to a hair's breadth as with rubber tires it noiselessly rolled along the asphalt with a motor power entirely hidden from view like some graceful animal curving its way in and out of traffic."2

While most Canadian carmakers began in Ontario and Quebec, British Columbia's rugged road conditions sparked some innovations here that were far ahead of their time: Vancouver's Max Goehler re-built his car with his own early version of all wheel drive in 1914.3

5. The Rich Man's Toy

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Duke of Conn P6

1912

Though this photo doesn't show a car, it shows the Duchess of Connaught as part of a royal visit. Early cars were expensive and widely seen as toys of the rich, which caused bitter class controversies. Back in England, a few years before this photo was taken, the Duchess caused a scandal when her chauffeur-driven car ran over and killed a child playing in the street and then drove off without stopping. Nobody was prosecuted, of course.1

* * *

An episode of the Simpsons, where Mr. Burns runs over Bart in his old fashioned car and drives off, seems to be based on an English horror story written over 100 years ago. In it a flamboyant Gatsby-like aristocrat spends his time driving around town and running over children for kicks.2

Suspicion of cars was not helped by the massacre at the 1903 Paris to Madrid race. The French were huge early car enthusiasts (the world's biggest car company in 1900 was French) and the race was advertised as the biggest ever. Hundreds of essentially home-made cars lined up at the starting line, with no safety precautions and no power steering. Practically none of the route was paved, so clouds of dust apparently blinded all the drivers who were reaching speeds of 140 km/hr. It's hard not to imagine an episode of the old TV show Wacky Races.

Unfortunately, hundreds of thousands of curious onlookers turned out to watch, many hoping to catch their first glimpse of an automobile. By the time the authorities shut down the race was before the Spanish border, 12 drivers and spectators had reportedly been killed and over 100 wounded.3

6. Barriers Come Down

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-5033

1912

Crews show off their service cars outside the headquarters of the B.C. Telephone Company (it's since been demolished). It took a little while for cars to gain acceptance, but as they became cheaper more people had access to them, and automobile associations were formed to lobby the governments for laws more favourable to car owners.

* * *

The enthusiasts, who were usually rich, banded together to form car clubs like the Automobile Club of Great Britain, the American Automobile Association, and the Canadian Automobile Association. They didn't only provide roadside assistance and promote car travel, they also lobbied governments to raise speed limits. 1903 was a turning point, at least in Britain, when the speed limit was raised to 20 miles per hour (32 km/hr).1 It took longer in British Columbia: In 1910 a man was stopped in Surrey for speeding and fined $10 – he was going 12 mph (20 km/hr).

Many people had good reason to see cars as dangerous machines; they were certainly far more dangerous than the cars we know today. Vancouver got its first motorized ambulance in 1909. The paramedics were so excited they took it out for a spin right away—and ran over and killed an American tourist.2

7. The Ford Revolution

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-88

1910

Harry Duker, owner of a billboard company, and his friends, pose with a bear they've shot in their Model T. Cars gave people easy access to the woods and the countryside like never before, allowing people to zip in and out of town for day trips. The Model T was revolutionary because it was rugged and sturdy and relatively cheap—an easy to use car that became the symbol of middle class success.

* * *

Henry Ford did take the obsession with streamlining and standardization a little too far. The Model T was the only car the Ford Company built and Henry Ford rather bizarrely refused to update it, saying "We want the man who buys one of our products never to have to buy another. We never make an improvement that renders any previous model obsolete." He adamantly refused to offer the car in different colours either, saying "You can have it in any colour, so long as it's black."2

Today many people look back on the jobs at Henry Ford's factories as representative of a king of golden age in America and Canada, and many politicians clamour to bring back those jobs. While Henry Ford did pay his workers well, their working conditions were anything but enjoyable. The assembly line workers were treated like human robots, punished if they were caught speaking, sitting, or standing still on the assembly line. He hired thugs that patrolled the factory floors, sometimes beating up workers and on occasion killing union activists. Company representatives enforced a mind-bogglingly intrusive morality code, which included unannounced visits to worker's homes to make sure they were clean and met a range of bizarre regulations. They might even ask pointed questions about the types of sex the worker had with his wife (all the workers were men and they were all required to have a wife). If they gave any answer the inspectors didn't like they could be fired on the spot.

Henry Ford was also a war profiteer and avoided paying millions in taxes during World War I. He also hated Jews, and was a rather big fan of Hitler's (the admiration was mutual and Hitler had a giant portrait of Henry Ford in his study).3

8. Rugged Canada

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-2-: CVA 677-420

1912

A Model T can be seen if you zoom in on the right side of the arch erected by the German community to mark the visit of the Duke and Duchess of Connaught. The Model T was especially popular in Canada, where its durability was well suited to Canada's terrible weather, long distances, and rugged terrain.

* * *

As a result early carmakers had a hard-timing pushing their products. William Still, a seller of electric cars in Toronto in the 1890s, complained about Canadians' irritating mixture of "American pushfulness and Scottish caution." Every conversation with a potential customer would end with them asking him if he was "aware of how cheap horses are."1

Henry Ford's Model T could survive on rugged roads, was easy to repair, and worked reasonably well in the cold. It was the most popular car in Canada until its last year of production, 1926.2

9. Before Paved Roads

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-1---: M-14-41

1912

Cars parked in front of the Birks Building while it was under construction. You can see the white Vancouver Block on the right is still standing. The roads here look paved, but paved roads were a rarity around these times, and driving between cities was always a hazardous adventure.

* * *

In British Columbia people drove on the left until 1922.2

As late as 1934 there was only 47 miles of what we would consider paved road in British Columbia. As one academic wrote, “Motoring was still a series of adventures in which the driver pitted his skill and his luck against mechanical imperfections and the hazards of the road.”3

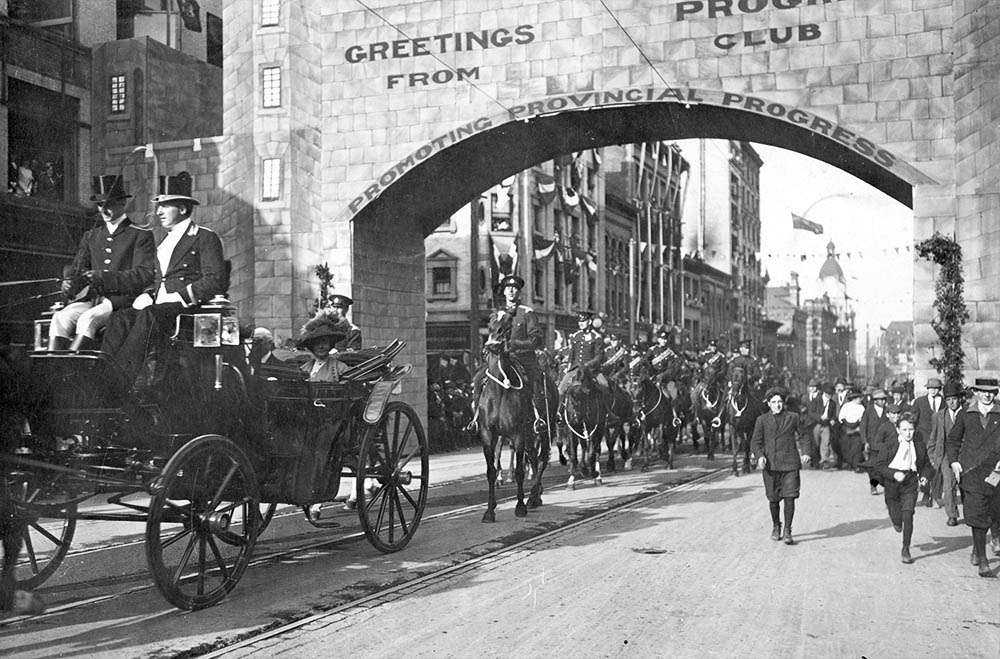

10. The Car Comes of Age

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Duke of Conn P25

1912

Hundreds of people and their cars have turned out to watch a ceremony to welcome the Duke and Duchess of Connaught to Vancouver. There is barely a horse in sight. At the time this photo was taken there were 1,769 cars on Vancouver's increasingly crowded roads. Traffic congestion was reported for the first time that same year.1

* * *

A whole economy began to sprout up around the cars. Something as obvious to us as a gas station had to be invented, and the first one in Vancouver opened in 1907 a few blocks from here at Smithe and Cambie. It was a rustic affair and gas was poured by hand into a funnel and down a garden hose into the fuel tank. Three or four cars was considered a busy morning.3

11. GM Steals the Throne

Vancouver Archives VPK-S625-: CVA 357-2

1925

A variety of cars parked in front of the former Saint Julien Apartment Block on Georgia Street. Going into the 1920s the dominance of Ford and the Canadian carmakers like Russell, gave way to the rising Canadian-American giant, General Motors. General Motors began when it absorbed McLaughlin, Canada's biggest car company, and then began absorbing dozens of new companies all over the world. By the 1930s the combine of companies had pioneered many aspects of the car business we take for granted today.

* * *

Sloan implemented the idea having each of his companies update their car models every year, a practice emulated by practically every car company today. Before GM, cars were simply marketed as tools to get you from point A to point B. Sloan turned that logic on its head, using advertising to make cars symbols of power, wealth, and freedom. Each of the car companies within GM would have a definable brand and look, so that people could tell a Chevrolet apart from a Pontiac at a glance. People were encouraged to climb the brand ladder as they proceeded through life, starting out with a Chevrolet, then moving up to a Oldsmobile, then a Pontiac, then a Buick, and finally the ultimate level of luxury, the Cadillac. They also came in a variety of colours.

After almost 20 years of producing largely unchanged Model T cars, it slowly dawned on Henry Ford that his cars were becoming obsolete. In 1927 he entirely shut down his factories for six months while they retooled to sell new Model A cars, laying off most of his work force in the process. The setback proved to be devastating, and GM vaulted past Ford in market share. Ford would never regain its place as the world's largest car manufacturer. Sloan had created, what one historian called "the world's biggest, most successful, profitable industrial enterprise in history."

GM expanded its global reach, buying up carmakers like Germany's Opel and Britain's Vauxhall. In 1945 however they passed on the chance to buy the little German carmaker Volkswagen. As Volkswagen is now bigger than GM, that proved to be a regrettable decision.1

12. The Car Society

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-1842

1928

Attendants on Georgia Street test people's brakes, part of the "Save a Life" campaign in an era when brakes were far less reliable than they are today. By the end of the 1920s cars were part of the fabric of urban life. They changed the way people worked, ate, holidayed, and socialized. Over the past 90 years those routines have expanded and become set in stone, so that it's increasingly difficult to imagine what life was like before cars. It's worth taking a moment to reflect on just how fundamentally cars have reshaped our lives.

* * *

At the same time our reliance on cars completely altered the way our homes, neighbourhoods and cities look. Suburbs meant people could live in bigger and bigger homes surrounded by paved roads and strip malls. Downtown cores on the other hand were hollowed out or filled with parking garages, gas stations and traffic-filled expressways.

By the 1970s more Canadians were living in suburbs than in urban areas or the countryside. Highways knitted cities and communities together, fostering interconnectedness and allowing people to move to new communities.1

Building and maintaining our cars also became a titanic industrial enterprise, creating many of the biggest companies in the world. The oil that fuels our cars has became a central national interest, its possession and extraction causing wars, pollution, and climate change.

It is so very difficult to imagine a world without cars today. Practically every aspect of our daily lives has become entangled with them and the services they enable. On the grand scale, the politics and economics of our global civilization have been largely designed to enable our continued addiction to cars. That very addiction may one day prove our undoing as the effects of climate change become more obvious every day.

Endnotes

1. The Car "Fad"

1. Berton, 15.

2. Berton, 14.

2. German Birthplace, French Nursery

1. Parissien, 4.

2. Parissien, 25.

3. Steam, Electricity or Gasoline?

1. Durnford.

2. Parissien, 15.

4. Canada's Car Industry

1. Durnford.

2. Davis.

3. Durnford.

5. The Rich Man's Toy

1. Parissien, 59.

2. Parissien, 70.

3. Caotica. Blog.

6. Barriers Come Down

1. Parissien, 55.

2. Davis.

7. The Ford Revolution

1. Siu.

2. Parissien, 32.

3. Parissien, 30.

8. Rugged Canada

1. Durnford.

2. Durnford.

9. Before Paved Roads

1. Durnford, 26.

2. Davis.

3. Glazebrook, 445.

10. The Car Comes of Age

1. Davies.

2. Berton, 15.

3. Glazebrook, 445.

4. Davies.

11. GM Steals the Throne

1. Parissien.

12. The Car Society

1. Soule, 42.

Bibliography

Caotica. The Race of Death! – Paris – Madrid Road Race 1903. Online.

Berton, Pierre. Marching As To War: Canada's Turbulent Years, 1899-1953. Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2002.

Davis, Chuck. The Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Vancouver: Coastal Publishing, 2011.

Durnford, H. & Baechler, G. Cars of Canada. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1973.

Glazebook G.P. de T. A History of Transportation in Canada Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1938.

Parissien, Steven. The Life of the Automobile: The Complete History of the Motor Car. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2013.

Siu, Jason. "Top 10 Best-selling cars of all time." AutoGuide. 9 Feb. 2012. Online.

Soule, David. Urban Sprawl: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. London: Greenwood Press, 2006.