Walking Tour

Outdoor Exhibits of the Toronto Railway Museum

Museum Audio Guide

Welcome to the Toronto Railway Museum’s Roundhouse Park Audio Guide. This Audio Guide will explain the history of many of the artifacts that you see around you.

This project is the result of partnerships with the Little Italy College Street BIA, the Toronto Chinatown BIA, and the Toronto Railway Museum.

1. Welcome to the Outdoor Exhibits

Our mission, represented by the exhibits, is to present the history of Toronto’s railway and to explain their significance to our city, communities, and our nation. As the great poet and playwright William Shakespeare once wrote, “What’s past is prologue.” Please note, some of the cars and locomotives described in this guide may have been moved inside the Roundhouse on the day of your visit. Some of the buildings may be closed. This is for restoration or maintenance. The Audio Guide narration will take about forty-five minutes to an hour. But you are welcome to take as long as you like. Please check out the Interpretive Plaques located across Roundhouse Park for additional information and insights. Feel free to stop at any point, take photos and videos, and if the exhibits are open, to tour inside. Our very knowledgeable guides, known as docents, will be happy to show you around and answer your questions.

2. John St. Roundhouse

The John Street Roundhouse, where the Toronto Railway Museum is located, was built in nineteen twenty-nine by the Canadian Pacific Railway, or CPR for short. It was used to house and repair its large fleet of passenger locomotives travelling through Union Station. It was last used in nineteen eighty-six.

* * *

The John Street Roundhouse was a very active industrial building. It was in use twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week until the end of the nineteen fifties. This was when diesel locomotives completely replaced steam locomotives, a process that began in the nineteen-forties.

The John Street Roundhouse was an eco-innovator for its time. This is due to its use of direct steaming technology. The Roundhouse used steam from steam heating plants for buildings like the Royal York Hotel and Union Station to warm up the locomotives’ boilers.

Steam locomotives and most buildings of that era used coal. Direct steaming cut down on the burning of coal and the harmful emissions that it releases. Yes, greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide or cee-oh-two, and sulfur dioxide or ess-oh-two, that is linked to acid rain, just to name two. Not to mention soot, that can harm the lungs and heart. The introduction of diesel locomotives cut down, but not eliminated pollution.

Today’s diesel locomotives, like you see on trains today, are much cleaner than their predecessors. GO Transit, the Toronto area’s commuter and regional rail and bus network, is looking at electrifying trains from clean energy sources.

Just west of the John Street Roundhouse was another roundhouse, the Spadina Roundhouse, which was built for the Canadian National Railways, or CNR, or CN for short. It was demolished in nineteen eighty-six to make way for the construction of the Rogers Centre and several condominium buildings.

In nineteen ninety the John Street Roundhouse was declared a National Historic Site. It is described as a quote “architecturally and historically important surviving reminder of steam technology and role of rail transportation in the city of Toronto.” End quote.

Where are the locomotive maintenance facilities today? You will find out shortly.

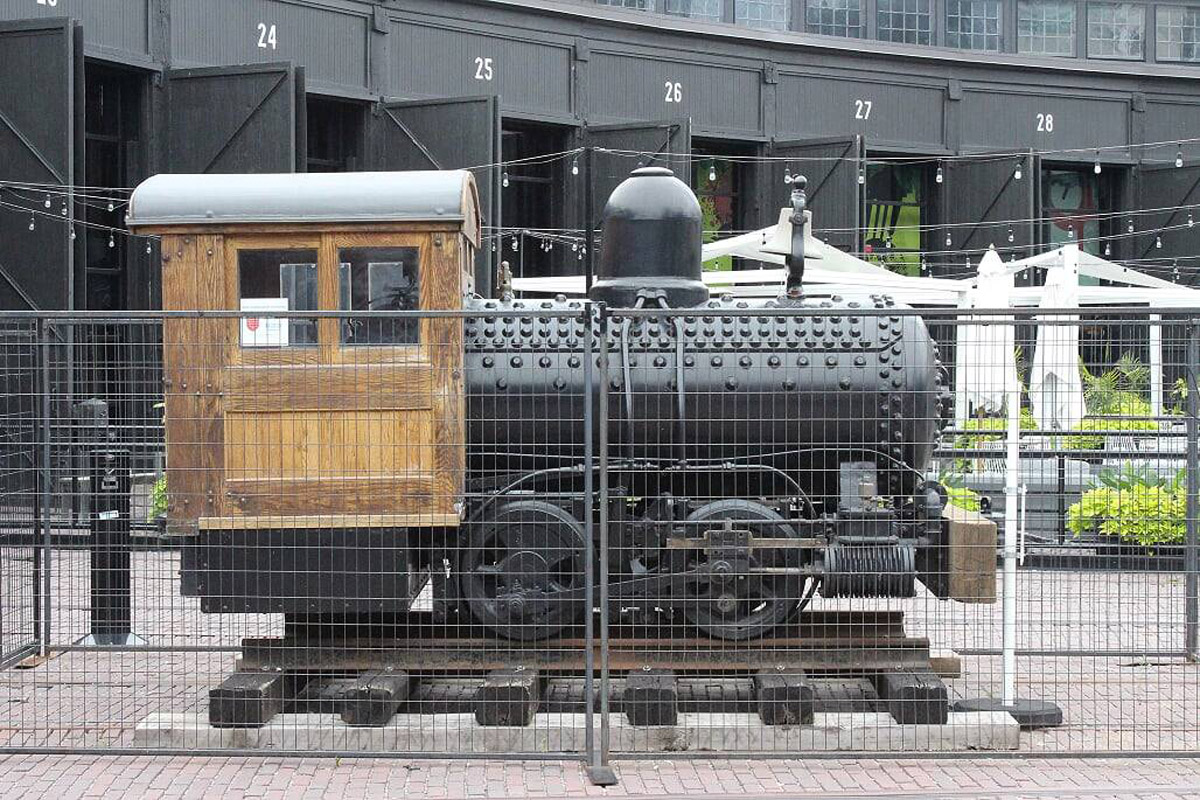

3. HK Porter Compressed Air Locomotive

The Porter Locomotive is the ultimate “green machine”. Instead of fossil fuels, it used compressed air for power, making it useful for specific industries, such as rope making. Because fuel is flammable, and could easily set things like rope on fire, an engine like the Porter here would prevent that.

* * *

4. CPR #7020

Seventy twenty is a diesel-electric switcher. It was built by the American Locomotive Company, in partnership with General Electric, in the USA, in nineteen forty-four. It is called diesel-electric because it has a diesel engine that turns a generator which creates electricity. The electric power is then supplied to the motors on the axles. Nearly all diesel locomotives in North America are the diesel-electric type.

* * *

It is hard to believe, but much of downtown Toronto was made up of factories, warehouses, and yes, rail yards. Where Roy Thomson Hall is today the CPR had a big freight terminal that Seventy twenty and locomotives like it switched. Items from freight cars would be loaded onto trucks and delivery vans, and vice-versa. The trucks would serve customers that did not have railway tracks to their premises, like department stores and clothing manufacturers.

So, what happened? Factories and warehouses began moving to the suburbs, where land was cheaper. There they could build large, efficient single-story buildings that avoided moving items up and down elevators. At the same time governments began investing large sums of money into highways. Consequently, businesses switched most of their freight directly to trucks, especially for short and medium distances. The same new highways also prompted people to buy cars and drive more, instead of taking the train or buses or streetcars.

Cheap land and the need to consolidate facilities led the CPR and CN to move their freight yards, and their locomotive maintenance facilities, to the suburbs. Both railways also have large intermodal terminals, where containers are lifted from railcars to trucks, and vice-versa.

CN had a huge freight yard in Mimico, which is about eight kilometres or five miles west of Union Station. When CN moved most of its operations out, GO Transit and later VIA Rail, located their maintenance facilities on that site.

All of these changes left vacant—and valuable--land in the downtown. Even so, for efficient operations GO has two small yards on each side of Union Station.

5. Locomotive Turntable

In front of the Roundhouse is its Turntable, which is officially the longest turntable in Canada at over thirty-six point five metres, or one-hundred twenty feet long. Turntables were used to spin steam locomotives around to get them out of the workshops and onto the tracks. Steam locomotives generally operate with the crews looking straight over the wheels to the front.

* * *

At the Toronto Railway Museum restorations of our historic equipment are always taking place. Our volunteer staff work throughout the year to preserve them. Be sure to Like Us on Facebook and check frequently for updates, like when we are moving our locomotives and rolling stock.

To continue our work, we welcome your donations. To donate online, please visit the TRHA website. And if you are interested in volunteering, please email us at [email protected]. Or you can ask at the Museum or at the Gift Shop at Don Station when they are open.

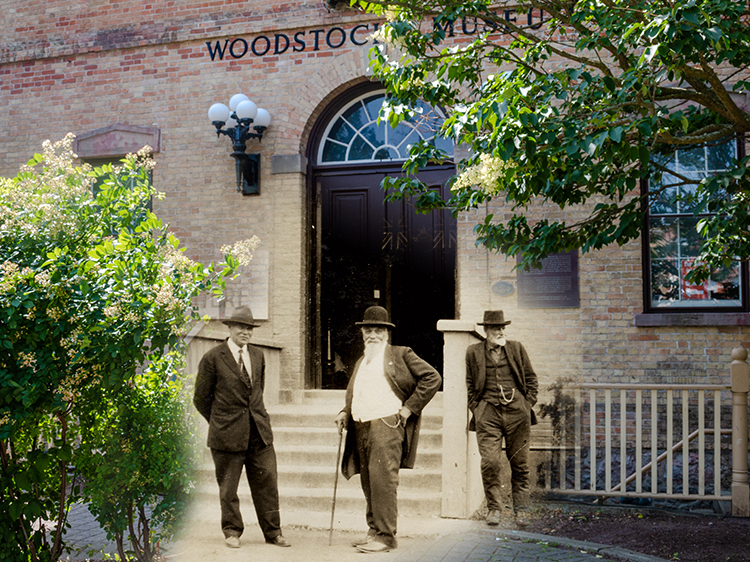

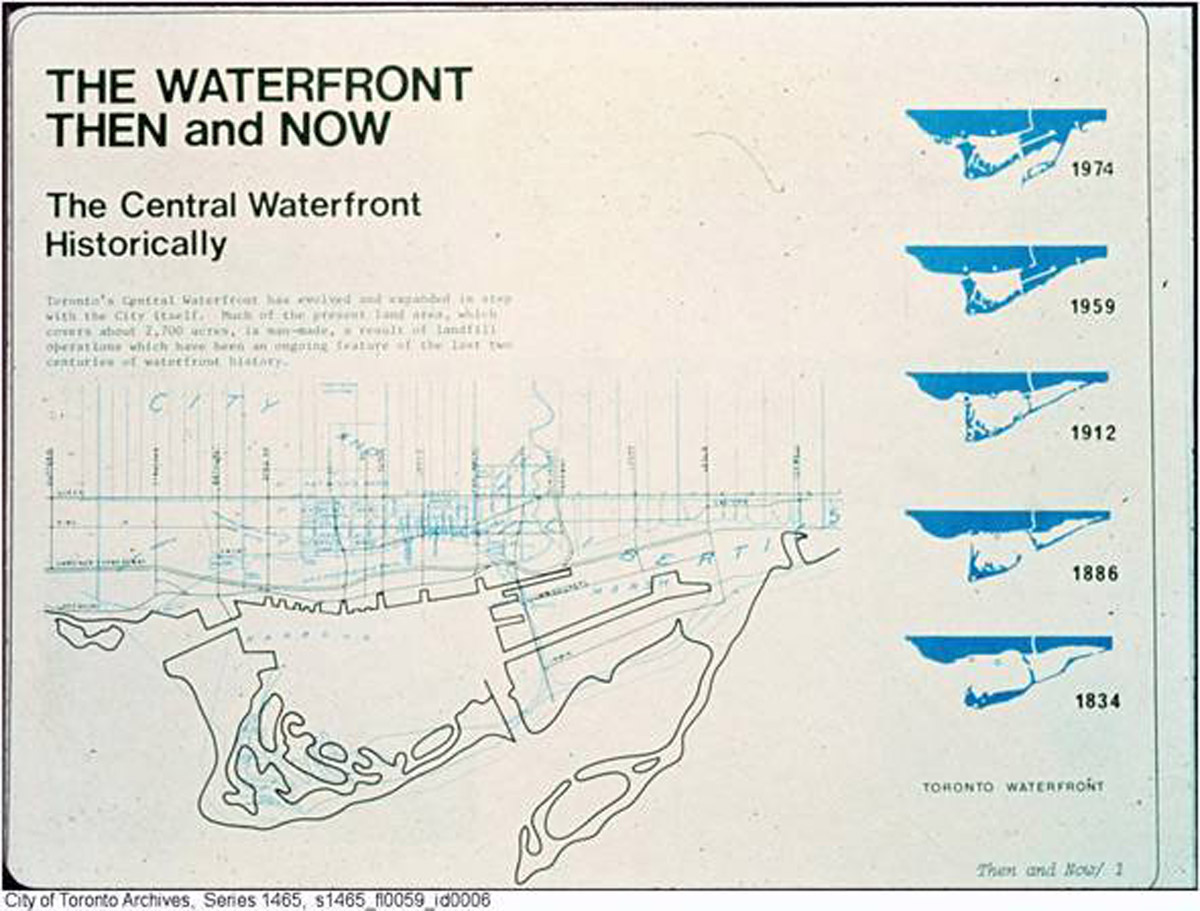

6. Toronto Railway Lands

Some 200 years ago the land around you did not exist, but the need for railways to access Toronto prompted civil engineers to fill in the shoreline and create artificial land. They used landfill that was dredged up from the bottom of Lake Ontario. This is why Front Street was so named, because it was originally on the waterfront.

* * *

In 1990 the John Street Roundhouse was declared a National Historic Site. It is described as an "architecturally and historically important surviving reminder of steam technology and the role of rail transportation in the City of Toronto."

7. CNR #6213

Here is our CNR steam locomotive, Sixty-two thirteen. But first, a little history of the CN is in order. Today CN is a private company, like the CPR. But the CN was formed in nineteen eighteen by the Government of Canada to fund and absorb financially defunct railway companies, such as the Canadian Northern Railway, and later, the Grand Trunk Railway. The government privatized CN in nineteen ninety-five.

* * *

The four-eight-four tells us the configuration of the wheels. The four wheels in the front and back are for steering the locomotive on curved tracks and to help support its weight. The eight wheels in the middle propels it. That is done through those big side rods that extend from the cylinders in the housings in the front.

The two sets of four wheels have other critical functions. Those in back support the cab, where the crew sits. It also carries the firebox, which turns fuel, in sixty-two-thirteen’s case coal. But steam locomotives sometimes used heavy oil, into hot gases. These travel through a boiler, heating up the water inside, thus creating steam. The steam then travels through pipes into the cylinders, which pushes the pistons and turns the wheels. This makes the distinctive chugga-chugga noise. The cylinders are supported by the set of four wheels in the front. Some of the steam was also used to heat passenger cars.

Trailing behind Sixty-two thirteen is a railcar that is called a tender. It carries both the fuel and water. Now if you are familiar with Thomas the Tank Engine it has tanks on each side, which carry the water and there is a hopper behind the cab to carry the coal. But the tanks and hopper are small, which meant that these locomotives cannot travel far without refueling. As a result, most steam locomotives have tenders. But tank engines were used for limited purposes, like at roundhouses, at industries such as mines and for logging, and for commuter trains.

8. GO Transit Cab Car

If you live or visit Toronto chances are you will have seen, heard of, and ridden on the GO train. The GO Transit commuter trains operate on the tracks below the overhead walkways and bridges between Union Station and Front Street and the CN Tower. The GO trains are typically made up of cab cars that have full operator controls, coaches, and one, but sometimes two locomotives.

* * *

This car was retired in nineteen ninety-four from GO Transit, replaced by the multilevel cars we see today. It was then used on Montreal area commuter trains. In twenty seventeen it was reacquired by Metrolinx, which is the Crown corporation which operates GO Transit. Metrolinx restored the cab car to its original appearance to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of GO Transit. The corporation then donated it for permanent display here at the Toronto Railway Museum.

This GO car symbolizes a revolution in transportation. GO was the first purpose-built commuter rail system in North America. It replaced a handful of commuter trains that had older equipment on limited schedules. The GO logo is appropriately green because planners and governments, even back in the nineteen-sixties, began realizing that we can’t keep building expensive urban highways congested with polluting cars.

GO Transit proved that people would get out of the cars and ride trains. It inspired cities like Vancouver and Los Angeles to introduce commuter rail and for other cities that still had it to modernize their systems. In fact, many of these new systems bought copies of the GO multilevel cars. They too were designed here in Canada and first built in Thunder Bay. The GO multilevels were the first true multi-deck commuter railcars. Other multideck railcars generally have their upper seats in galleries above the first level seats.

9. TH&B #70

Here is our Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway Caboose Number Seventy which was built in Berwick, Pennsylvania in nineteen thirteen. The TH and B, now owned by the CPR, links Toronto with the American railways at Buffalo and serves the steel mills.

* * *

Inside our caboose you would see many things that would be necessary for a train crew to be comfortable and productive. You have bunks for sleeping, desks for paperwork, a stove for cooking, and a closet for the toilet. Most importantly, there are two brake wheels on each end for the brakemen, and yes in those days it was men who did that job. There is a cupola for the conductor to see above or alongside the train. He could then ensure that the train cars hadn’t derailed or had caught fire.

The amenities on a caboose were a necessity. That is because crews aboard cabooses lived in times where labour laws didn’t govern how much they could legally work before having time off. So, as a result, they often spent long periods travelling.

Cabooses were gradually phased out as new technology called Flashing Rear End Devices were introduced. There were far fewer fires when railcar axles switched to roller bearings from friction bearings. Meanwhile labour laws reduced the time crew spent on the rails. Ultimately the railway companies wanted to lower their staffing expenses. This would help keep them competitive with the trucking companies and with the St. Lawrence Seaway.

This caboose is especially significant for the Toronto Railway Museum. It was recently restored completely by our skilled volunteers to its operational appearance in the mid-nineteen fifties. We have other similar restoration projects underway and planned.

10. CNR #79144

CN Caboose #79144 has a rather interesting origin story. It started life as a wooden box car built by the Eastern Car Company in 1920. Wooden boxcars were discontinued in favour of all-steel boxcars later that same decade, and by the 1950s wooden boxcars were being phased out.

* * *

A developer acquired Picketts Nurseries and donated the caboose to the museum in 2014. On its arrival a team of volunteers began restoring the caboose inside and out. As we already have our Toronto, Hamilton, & Buffalo caboose on display for the public, we are currently using this caboose as an extension of our museum's operational space.

11. CNR #4803

Here is our CNR GP seven diesel locomotive numbered Forty-eight zero three. It was built by General Motors in nineteen fifty-three. The GP seven is our example of the technological shift from steam locomotion to diesel that was completed in the 1950s.

* * *

But what really gives diesel locomotives like the GP seven their superiority over steam locomotives is their greater versatility. They can be coupled together to pull longer and faster trains. And operated with the same number of crew members. That made them more powerful and efficient than the CNR sixty-two thirteen. This is done with what is known as multiple unit or MU controls. But the diesel locomotives can also be operated in single units for shorter trains. Whereas railways had to have many different types of steam locomotives for specific purposes.

Today quite a few GP series of locomotives are still in service as switchers. They have the shorter of the two hoods from the cab cut down for crew visibility. This really goes to show how good the concept was and how well built these locomotives are.

At each end of the locomotive there is a big hose in the centre. It is for the air braking system. And above the hose is the automatic coupler. It is used to connect the locomotive with other locomotives and with freight and passenger cars.

The air brakes and automatic couplers are why we have safe trains today. Air brakes stop trains when the train operator, commonly known as an engineer, opens a valve. Or if the trains uncouple accidentally. In both cases the air is released from the system, forcing the brake shoes against the wheels.

Before there were air brakes crewmembers had to climb onto each car to turn hand brakes, leading to many accidents and injuries, and yes, deaths. While steam locomotives and cabooses, like we will see later, also had brakes, they were inadequate for longer trains.

And before automatic couplers were introduced coupling was done by hand. It was also extremely dangerous, often resulting in severe injuries and deaths.

12. CPR Cape Race

Cape Race is our luxury solarium passenger car. It was built in nineteen twenty-nine for the CPR as a lounge car for the Trans-Canada Limited series of trains that ran from Montreal and Toronto to Vancouver. Sleeping rooms were added in the nineteen-forties to provide revenue. This car, and others like it, were originally named after famous Canadian rivers. Cape Race was first known as River Liard, after the river that runs off of the Mackenzie River in the Yukon and British Columbia.

* * *

Following weight-reducing renovations, the River Liard was renamed to Cape Race. Cape Race was named after a cape in southeast Newfoundland and Labrador. It is famous for receiving the distress signal of the sinking Titanic and relaying the message to the rest of the world.

When big steel heavyweight cars were phased out in favour of streamlined cars, Cape Race served as a business car until nineteen sixty-nine. Then it was sold to the Upper Canada Railway Society for railway excursions. The car was donated to the Toronto Railway Museum in two-thousand eight.

Inside Cape Race there are buzzers between each window. Passengers would use them to call for porters. They were almost exclusively black Canadians, and their service aboard sleeping cars is crucial to telling the story of minority communities in Canadian history.

Unfortunately, black porters were often treated very poorly by passengers and by their supervisors. They were derogatorily referred to as “George” (the name of a famous American railway magnate whose company made and operated sleeping cars). But their employment afforded them a stable income, which most black Canadians did not have in the early twentieth century. There is a great book written by a Canadian historian and former sleeping car porter named Stanley G. Grizzle called My Name’s Not George.

This stable income gave black porters a platform for political prominence and to become leaders in their communities. In nineteen forty-six black Canadian porters were organized by an American union called the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters as a Canadian chapter. It became the first trade union in Canada organized by and for black Canadians. The union pioneered the civil rights movement in Canada in the process. Canada’s new ten-dollar bill also honours a black civil rights pioneer, Viola Desmond.

13. CPR Jackman

Our Jackman passenger car was a 14 section sleeping car built by Canadian Car and Foundry in 1931. It's an example of standard overnight accommodations that can be found in Canada prior to the 1960s. Accommodations consisted of 14 upper and lower bunks, seven on each side of the car. During the day the lower bunks could be folded into a pair of coach seats. At each end of the car there was a large washroom: One for men with a smoking lounge, and another for women without a smoking lounge but with additional sinks, mirrors and other amenities.

* * *

Beds were prepared, curtains arranged, and ladders provided by sleeping car porters, a profession traditionally reserved for black Canadians. Unfortunately, black porters were often treated poorly by passengers and their supervisors. They were often derogatorily referred to as "George", the name of a famous railway magnate whose company made and operated sleeping cars. Their employment afforded them a stable income, a benefit not afforded to many black Canadians in the early 20th Century. This gave black porters a platform for political prominence and the ability to become leaders in their communities.

In 1946 black Canadian porters were organized by an American union called the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters as a Canadian chapter. It became the first trade union in Canada organized by and for black Canadians, pioneering the civil rights movement in Canada in the process.

In the late 1960s or early 1970s this car along with several others like it from the first half of the century were put into maintenance of way service. Maintenance of way crews who worked to maintain the track across the Canadian Pacific system would live out of this car while going to work on sections of track in rural areas that are inaccessible except by rail, such as parts of northern Ontario.

It ended up in the collection of the Upper Canada Railway Society, who generously donated it to the City of Toronto. We plan to restore this car and make it a keynote exhibit on the history of immigration, railways, and the history of Toronto.

14. Don Station

Don Station is an original train station that was situated on the west bank of the Don River just south of the Queen Street Bridge, which is east of here along King Street. It was built in eighteen ninety-six to serve CPR passengers who lived in the east end of Toronto. In nineteen sixty-seven it was closed and moved to Todmorden, north of the downtown, before being moved to Roundhouse Park in two thousand eight.

* * *

At one time Toronto had many such local stations that were later abandoned. Metrolinx is bringing them back in several locations, with new stations planned, such as at Liberty Village and St. Clair West. Many people now live in these areas, which have also attracted businesses. Toronto has become a leading global technology hub as well as Canada’s financial centre.

Inside of Don Station the largest room was a passenger waiting area which is now our Gift Shop. It has adjacent rooms including a baggage room, a station operator/ticket office, and also a washroom. The Gift Shop at Don Station is where you can buy tickets for the Roundhouse Park Miniature Railway when it is in operation.

And that concludes our audio guide. We hoped you found the guide fun and informative. And we welcome your feedback. Please click the stars at the top of the app screen to provide your comments.

Thank you very much for joining us and helping support the preservation of Toronto’s railway heritage!

15. Cabin D

At the east end of Roundhouse Park is the two-story building labeled Cabin D and an adjoining toolshed. It is called Cabin D because there were once several lettered and also named switching stations located along the tracks stemming from Union Station. These switching stations are being phased out by more advanced technologies.

* * *

All switching towers were elevated to give operators a clear view of the tracks, including signals. Looking at the shingle skirting and the upturned roof design of Cabin D, you can see elements of Asian pagoda design. It was quite popular in North American architectural designs in the late Nineteenth Century.

In towers like Cabin D switch operators would pull or release levers that were connected to long metal rods that would open or close track switches. They have locking mechanisms that prevented someone causing one train to collide with another train.

Interlockings are still used today, but they are electrically and electronically operated. And their towers are now out of sight of the tracks. Tower operators no longer need to see where trains are to route them safely. Track circuits, which are tripped when a train rolls over them, and in the near future GPS systems, tell the personnel where the trains are.