Walking Tour

Beyond Chinatown

Toronto's Chinese Community

Alexa Dagan & Natalie Dunsmuir

City of Toronto Archives Series 1465, File 344, Item 11

In the heart of modern-day Toronto sits the sprawling block of civic governance at the northeast corner of Queen Street East and University Avenue. This block contains Toronto's current city hall and law courts as well as the "Old City Hall" located on the other side of Yonge Street. While anyone can walk through the square and admire the stately buildings, not every visitor is aware of what was lost when the square was developed into its current incarnation. Before city hall, this block was home to Toronto's first "Chinatown", which stretched along the section of Elizabeth Street that was blocked off and demolished to make way for the new civic centre.

While most of the buildings were lost in the construction, many of Chinatown's residents and businesses moved several blocks west, and today, Chinatown is centred on the intersection of Dundas and Spadina.

This tour tells the story of downtown Toronto's Chinese community, exploring the lives of the people who made their homes on Elizabeth Street, their fight to save it from development, and the renewal of Chinatown in more recent decades.

The tour begins in the square fronting city hall, where we will start our story with Chinese immigration to Canada. As we walk north up Elizabeth Street, we will learn more about the neighbourhood known as "The Ward" and about some of the businesses that were common in early Chinatown. Next, we will head west along Dundas for a few blocks. As we take in the sights along this street, we will discuss the importance of restaurants in Chinatown and learn about the transition from the "Old" Chinatown to the "New" and about the community activists who fought to preserve Elizabeth Street. As we resume our northward journey by turning right onto Spadina, we will reflect on Chinatown's connections to Toronto's other immigrant communities and on the journey the community has taken into today.

This project is the result of partnerships with the Little Italy College Street BIA, the Toronto Chinatown BIA, and the Toronto Railway Museum.

1. "Journey of a Thousand Miles"

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 32, Item 187

May 15, 1913

Before the construction of city hall and the large, open square that fronts it, this block was Elizabeth Street, home to Toronto's first Chinese neighbourhood. In this photo, a young child stands at the rear of the building at 92 Elizabeth. Many of the first Chinese settlers in this neighbourhood were impoverished workers who came to Canada in search of opportunity. For many, settling in the growing community centred on Elizabeth Street marked the end of a long and arduous journey.

* * *

In 1859, the Qing or Manchu Dynasty lifted an edict against emigration from China that it had imposed in 1672. For many, this change was a chance to seek opportunities elsewhere. For the struggling peasant class, namely from the Guangdong province in southern China, life had become almost unbearable. A burgeoning population had stretched the Empire's ability to feed its people to a breaking point, a situation which was further exacerbated by a series of floods, typhoons, droughts, and other disasters in the most densely populated area of the province. The labourers and farmers of the peasant class felt the weight of these disasters most keenly.

When the Qing government imposed taxes on the poorest portion of the population to cover the indemnities imposed by the British after the Opium Wars, it was a financial burden few could afford. However, a rumour began to spread throughout Guangdong that promised a small measure of hope. In 1858, gold was discovered in the Fraser River in British Columbia, Canada. The news of this find, and of the lucrative opportunity it presented, spread across the world. In China, the news sparked stories of a place that became known as Gum Shan, or Gold Mountain. And while the elusive rumours of gold were enough to persuade some to make the arduous journey to North America, it was the far more tangible promise of paid labour that prompted many more to follow.

In the 1880s, Canada began construction on one of the most intensive and expensive infrastructure projects it had ever undertaken. The transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway was meant to connect the country and open new lands to settlement. The biggest obstacle to its completion was crossing the Rocky Mountains to reach the Pacific Ocean. To complete this portion of the railway, Prime Minister John A. MacDonald approved the CPR's decision to hire thousands of Chinese labourers. Not only could the CPR get away with paying these labourers far less than white workers, but the Chinese workers also had little bargaining power to protest the outrageously poor working conditions on the railway.

When the railway was completed, not only had many Chinese workers died in the process, but very few left the project with any financial gains to show for their ordeal. A scant few were able to afford passage back to China. Thousands more were stranded in a province that was at best unwelcoming and at worst, actively hostile. Finding little opportunity in BC, many began to travel east. In 1878, the first Chinese settler was recorded in Toronto's city directory.3 Many more would follow. Thus began the establishment of Toronto's first "Chinatown" on Elizabeth Street.

2. The Ward

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 33, Item 257

Dec. 2 1937

Joe's Cafe, pictured here, stood on the corner of Elizabeth Street and what was likely Albert Street. Both streets ran through this block before it was closed off for the construction of the new city hall. Cafes such as this were once among the most common businesses one would find in Chinatown. They offered affordable, filling meals suited to both western and Chinese palettes.

* * *

This neighbourhood had a reputation as a landing site for new immigrants. Before the Chinese settlers moved in, The Ward had been home to immigrants from Eastern Europe and Italy. From 1905 to 1912, a large Jewish population lived there, but rising rents, increased demand for housing, and neglectful landlords eventually prompted them to move on. The Jewish businesses moved westward to Kensington Market, and the Italians moved to "Little Italy" at College and Grace Streets.

The Ward was known as a low income area and was composed of small, crowded cottages that landlords refused to maintain or upgrade, and narrow, unpaved alleyways. However, with the European immigrants moving on to new areas and after the Chinese settlers had been repeatedly forced out of their previous residences by development, Elizabeth Street offered shelter and, more importantly, space for a community to take root.

While the Chinese immigrants had settled into a neighbourhood few others wanted, not everyone welcomed their presence in the city. One article published in the newspaper Jack Canuck makes it clear that anti-Asian racism was prevalent in Toronto: "There are not less than 25 Chinese stores, laundries and restaurants in the blocks bounded by King, Queen, Yonge, and York Streets. How many of them are 'dens' in the police court parlance? One need only stroll through the above mentioned blocks and notice the throngs of Chinese lounging in the streets and doorways to realise the 'Yellow peril' is more than a mere word in this city."2

However, despite the hostility from much of Toronto's white community and despite other factors that prevented them from entering the workforce such as limited English and skill barriers, Toronto's Chinese settlers were able to find their niche. For many, previous experience in other parts of Canada and the United States had made clear that laundries and restaurants were two areas in which Chinese immigrants could make a living. Both of these businesses were some of the first Chinese-owned operations in Toronto, and in the early 20th century, restaurants and laundries composed a large number of the businesses that were owned and operated by Chinese immigrants.

Chinese laundries and restaurants in Canada had a history which went back to the gold rush. In frontier gold rush communities, anti-Asian sentiments were often very strong. As Chinese men were driven from the gold fields and prevented from finding other means to support themselves, they began exploring other options. Laundry would not have been the first choice for many. Chinese men viewed laundry as women's work, perhaps to an even greater degree than white men did. However, they had few options, and not only were laundries a necessary service, but they had the added benefit of low start-up costs and operating overhead, and they required little English or specialised skills. Restaurants and cafes were similar, although they required a larger upfront investment and a slightly higher overhead.

In 1881, when there were only 10 Chinese settlers in Toronto, there were already four Chinese-owned laundries. By 1905, this number had grown to 228.3

3. Soap

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 33, Item 255

Dec. 2 1937

In this photo, a laundry truck is parked on the street outside of 111 Elizabeth Street. For the men who opened laundries in Canada, it was an exercise in opportunity rather than preference. In China, laundry was women's work, and some Chinese men who came to North America following a gold rush would wear clothes until they fell apart or else send them home to China to be washed and returned months later. When earliest Chinese laundries began to appear during the gold rush period, they were often among the first businesses in town.

* * *

Laundries were small, practical spaces usually composed of a reception area and a workroom. In the reception area, wall-to-wall counters were lined with stacks of laundry parcelled in brown paper and labelled in Chinese. The workroom was full of kettles, wash tubs, scrubbing boards, and wringers. What little space was left was taken up by the stove or by washed clothes hanging to dry. The workroom also doubled as a living space.

Tom Lock, who worked in his father's laundry, described the process: "to make the linens white, we used to put the soiled linen in a big square steele tank 4'x4'x'6' deep on top of the coal stove. We would feed the tank using a hose and add bleach, stirring the washing with a big stick. After, Ma would stand on a stool, reach into the boiling water and drag out the clothes with the stick. She would then drop them in a pail and transfer them to the washing machine."1

However, even the modest living that Chinese settlers earned from laundries was often threatened. While laundries were a common occupation for Chinese men, they were not the only ones in the business, and white laundry owners soon began to resent the competition. Chinese laundries were initially tolerated, but after a few years, their competitors realised that the Chinese businesses were doing well and charging less—only 12 cents a shirt instead of the 15-18 cents typically charged by white laundries.2

White laundry owners and labour union leaders began fighting against the Chinese businesses, claiming that these establishments were edging them out of the business. The white Laundry Association, aided by local newspapers, launched a smear campaign to pressure public health authorities to close the "dirty" Chinese laundries. As a result, the Toronto Star published an article that read, "alleged by those who claim to know, that in most of these places their working boards are used for bedsteads, and the soiled linen which comes from the houses of Toronto citizens are utilised for bed clothes."3

When Ah Cong tried to open a laundry at 1061 Bathurst Street in 1906, property owners opposed his application at City Hall. The city then turned down his application because its Board of Control had visited the area and determined that it already had enough Chinese laundries.4

Even before Cong's struggle with City Hall, officials had attempted to limit the number of Chinese laundries. In 1902, the city passed a bylaw that attempted to regulate laundry businesses by forcing them to pay a licensing fee of $50. The bylaw, while not inherently discriminatory, was implemented in such a way as to disproportionately affect Chinese laundries. Their businesses were often smaller operations with limited employees and rudimentary machines. They could not afford the same fee that the larger, white-owned laundries could. Fortunately, a municipal alderman advocated on their behalf, and the fee was changed to a sliding-scale based on the number of staff that the establishments employed. The bylaw backfired on the white laundry owners. The smaller Chinese laundries paid as little as $5, while larger, white-owned laundries paid up to $20.5 (2.5)

4. A Watering Hole

City of Toronto Archive Fonds 2032, Series 841, File 46, Item 35

1972

The Continental Hotel stood on the northwest corner of Dundas and Elizabeth from the 1950s to the 1960s. Several marginalised groups found a tolerant space away from the public eye at The Continental. Chinese men, who were unable to bring their wives to Canada due to blatantly discriminatory immigration laws, found companionship here. Queer women also frequented the hotel, as the bar manager, Johnny, was known to both accept and protect his queer clientele. At the Continental, Chinese men, queer women, and sex workers had interconnected, social relationships with each other as groups that were discriminated against elsewhere.

* * *

In Arlene Chan's book on Toronto's Chinatown, Gim Won describes his memory of the head tax's effects: "villages did everything they could to send one person over, in hopes he would do what he could to help the village… Even when I was in high school I remember my parents still fighting every New Year's about whose village they were going to send $20 back to, my father's or my mother's. Our rent at the time was $5 a month, so $20 was a lot of money."1

The Canadian government made a total of approximately $23 million from the thousands of Chinese immigrants who scraped together the cash to pay the head tax. Coincidentally, the Canadian government spent about the same amount on building the BC portion of the CPR—the same railway that so many Chinese workers died to build.2

When the head tax was ended, it was only to make way for another discriminatory law, the Chinese Exclusion Act, which effectively banned any and all Chinese immigration. The effect these laws had on Chinese families was incalculable. The men who had travelled to Canada found it virtually impossible to bring their families over to join them. One man, who had himself arrived in Canada without his family, recalled, "I remember looking out over the big dining room of our restaurant on a busy day in 1946. I counted one hundred old Chinese men sitting out there and just six women, four Chinese and two Canadian. And I thought to myself, if Canadian culture has a Christian spirit, how could they deny Chinese their families? The whole city of Toronto didn't have a dozen Chinese women in 1946."2

For some of these men, the Continental Hotel offered something different from the bachelor society found in Chinatown. Queer women and sex workers also frequented the hotel. According to Professor El Chenier, who has done extensive research on LGBTQ+ communities in Toronto, "Up until the end of the 1950s, the police did not raid the Continental, and there are no records to suggest that any effort was made to force the owner or management to ban their lesbian customers, even though liquor licensing laws contained provisions that allowed them to do so,".3

Chenier also explains that some Chinese men and queer women lived together in arranged relationships. In these situations, the men would usually pay the bills while the women offered physical companionship.

While each of the disparate groups that spent time at the Continental endured discrimination for different reasons, the hotel provided a space where an unorthodox community could form away from the disapproving gaze of Canadian society.

5. A Labourer's Lunch

City of Toronto Archives Series 1465, File 519, Item 17

ca. 1980 - 1990s

This photo looks west down Dundas towards Huron. Today, if you look north up Huron Street from this intersection, you can view the statues in this public plaza, which are part of an initiative by the Chinatown Business Improvement Association to create a vibrant public space for casual use and community events.

Despite only being about 30 to 40 years old, the majority of the buildings shown in this photo have been renovated over the decades. While many types of businesses are visible in this shot, the most numerous are the restaurants. Chop suey, a dish that is commonly found in many Chinese-Western style restaurants today, is one menu item that has historic ties to the Chinese-owned restaurants that were prevalent in Toronto in the early 20th century.

* * *

On Elizabeth Street, two restaurants in particular gained notoriety: Hung Fah Low and Jung Wah at 121/2 Elizabeth. Their clientele were mostly Chinese, with some Jewish patrons, but the proximity of two vaudeville theatres meant that actors were frequent guests as well. Actor Edward G. Robinson, who was in over 100 films, claimed that "121/2 [Elizabeth Street] was the best place to eat."1

Chinese restaurant operators outside of Chinatown mostly ran small cafes and hamburger joints. They catered to Canadian customers and served dishes such as roast beef, steak, apple pie, and ice cream. Lithuanian men were known to pick up boxed lunches from these businesses on their way from the boarding houses where they slept to the factories where they worked. Chinese-owned restaurants were very affordable for a labourer and charged around 20 cents for soup, sandwich, and dessert.2

George Heron remembers that these restaurants were a "bonanza for the many unemployed men who crowded the city during the Depression years," and that, "On Queen Street near Sherbourne there were a couple of these restaurants which offered full course meals for 15 cents. By full course is meant soup, a Salisbury steak or fish main course with vegetables, a piece of pie and a drink of tea, coffee or milk. Not only that, each had plates piled high with white and brown bread."3.

In The Chinese in Toronto 1878, author Arlene Chan includes a quote from her father, Doyle Lumb, who worked at the Rex Cafe on Yonge Street in 1929. He recalled, "the Rex Cafe was considered one of the best restaurants. Got paid $3 a week. I worked every day, including Sunday, seven days a week, from ten in the morning to ten at night."4

6. Save Chinatown

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 200, Series 1465, File 519, Item 18

ca. 1980 - 1994

This photo shows the view looking east at the intersection of Dundas and Huron. In 1947, the city approved funding for a new city hall development which would cut through the heart of Elizabeth Street's Chinatown. The community's residents and businesses were not consulted, and the property owners were vastly undercompensated for the value of their expropriated properties. Much of the physical presence of Elizabeth Street's Chinatown was lost in the development, despite the efforts of dedicated activists. Its people moved several blocks to the west and set down deep roots around Dundas and Spadina. Today, this "New" Chinatown continues to commemorate the Save Chinatown Committee and their commitment to protecting their homes and businesses from urban development.

* * *

7. Chinatown(s)

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 2032, Series 841, File 74, Item 14

1972

This photo shows the Buck Gat Store on the corner of Dundas Street and Larch Street. Larch used to run here, but now it is blocked off by an entry to an underground parking garage. The New Ho King restaurant at 410 Spadina had their first location here, and today, it is the home of Biwon, a Korean restaurant. While this area is known as "Chinatown", there are three distinct and sizable Chinese-Canadian communities in downtown Toronto, and many more in the surrounding suburbs.

* * *

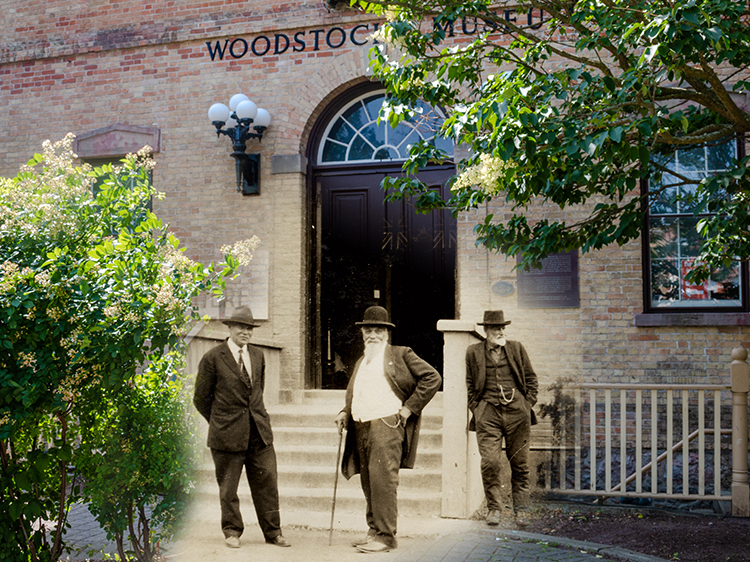

8. Commerce

City of Toronto Archives Series 1465, File 344, Item 11

ca. 1980 - 1990s

This photo shows a view of some businesses on Dundas Street in the 1980s or 1990s. The white building on the right of the photo with its distinctive triangular window is noticeably newer in this photo, while the brick building on the left appears to have been drastically remodelled. A sign advertises the services of a Chinese Astrologer. Scholars estimate that this cultural tradition has roots that date back around 3,000 years. As the face of Chinatown changed over the decades, small businesses such as restaurants and grocers blended in alongside modern shopping complexes, retail outlets, and gift shops.

* * *

9. Connections

Toronto Public Library 970-20-1 Cab

1910s

Today, the building on this corner is home to a popular chain donut shop, but in 1915 it was the Cut Rate Drug Store. In this photo, two men, a boy, and a lounging dog stand for a photo outside the business. The sign above their heads features the words "Cut Rate Drug Store", followed by a rendering of the English title in Yiddish script. Before Toronto's Chinese community moved into the Dundas and Spadina area, the neighbourhood was largely Jewish and Eastern European, much like "The Ward" had been in the late 1880s.

* * *

10. A Journey's End?

Toronto Public Library JRR 535 Cab

1863

This 1863 painting features the green lawn of Spadina Commons, which was once located on this spot. On the lawn, the Royal Regiment of Canada (later the Royal Grenadiers) parades during a ceremony where the women of Toronto presented the colours. The landscape of Toronto has changed significantly since the painter took up a brush. In the modern photo, a mix of trendy and old fashioned signs decorate brick buildings as steel and glass buildings and the CN Tower overlook the city. As the city changes, so do the attitudes held by those who call Toronto home, and the majority of people welcome the city's multicultural character. Yet the work is not finished, and Chinese-Canadians across the country still face outdated and racist mindsets from others in Canadian society. Despite this, Chinese culture, languages, cuisines, arts, and media thrive in Toronto more than any other city in Canada.

* * *

Endnotes

1. "Journey of a Thousand Miles"

1. City of Toronto, "T.O. Health Check," 2019, online.

2. Arlene Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle (Toronto, ON: Dundurn Natural Heritage Toronto, 2011), 17.

3. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 36.

2. The Ward

1. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 36.

2. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 37.

3. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 37.

3. Soap

1. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 46.

2. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 42

3. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 45.

4. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 44.

5. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 45.

4. A Watering Hole

1. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 32.

2. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 69.

3. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 83.

5. A Labourer's Lunch

1. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 49

2. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 50.

3. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 50.

4. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 51.

6. Save Chinatown

1. City of Toronto Archives, " Chinese History in Toronto," online.

2. City of Toronto Archives, online.

3. City of Toronto Archives, online.

4. Myseum of Toronto, "Jean Lumb: Toronto Stories," online.

7. Chinatown(s)

1. Arlene Chan, "Toronto Chinatown," The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 17, 2021, online.

2. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 155.

8. Commerce

1. Camille Bégin & Erica Allen-Kim. "History of the Dragon Centre," Dragon Centre Stories, online.

2. Brian McAndrew, "Chinese are moving to the suburban 'Asiancourt'", Toronto Star, May 14, 1984.

3. Bégin & Allen-Kim, online.

4. McAndrew, online.

5. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 159.

6. Chan, The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle, 178.

9. Connections

1. Jewish Virtual Library, "Toronto," online.

2. Jewish Virtual Library, online.

3. Ontario Jewish Archives, "Immigration," online.

10. A Journey's End?

1. Stephen Harper, "Harper Government Issues Full Apology For Chinese Head Tax and Chinese Exclusion Act," (Government of Canada, June 22, 2006, Ottawa), online.

2. Chan, 152.

3. "Another Year: Anti-Asian Racism Across Canada Two Years Into The Covid-19 Pandemic." Fight Covid Racism, Chinese Canadian National Council, Toronto Chapter. Online.

4. Chan, 177.

5. Clarrie Feinstein, "Can a 'cultural district' designation save Toronto's Chinatown," Toronto Star, Feb. 22, 2022, online.

6. Feinstein, online.

Bibliography

Bégin, Camille & Allen-Kim, Erica. "History of the Dragon Centre." Dragon Centre Stories. https://dragoncentrestories.ca/history-of-the-dragon-centre/

City of Toronto, "T.O. Health Check," 2019. https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/99b4-TOHealthCheck_2019Chapter1.pdf

City of Toronto Archives. " Chinese History in Toronto." https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/accountability-operations-customer-service/access-city-information-or-records/city-of-toronto-archives/using-the-archives/research-by-topic/chinese-history-in-toronto/

Chan, Arlene. "Toronto Chinatown," The Canadian Encyclopedia. March 17, 2021. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/toronto-chinatown

Chan, Arlene. The Chinese In Toronto from 1878 - From Outside to Inside the Circle. Toronto, ON: Dundurn Natural Heritage Toronto, 2011.

Chinese Canadian National Chapter, Toronto Chapter. "Another Year: Anti-Asian Racism Across Canada Two Years Into The Covid-19 Pandemic." https://ccncsj.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Anti-Asian-Racism-Across-Canada-Two-Years-Into-The-Pandemic_March-2022.pdf

Feinstein, Clarrie. "Can a 'cultural district' designation save Toronto's Chinatown," Toronto Star, Feb. 22, 2022. https://www.thestar.com/business/2022/02/22/can-a-cultural-district-designation-save-torontos-chinatown.html

Harper, Stephen. "Harper Government Issues Full Apology For Chinese Head Tax and Chinese Exclusion Act," Government of Canada. June 22, 2006. https://www.canada.ca/en/news/archive/2006/06/prime-minister-harper-offers-full-apology-chinese-head-tax.html

Jewish Virtual Library. "Toronto." https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/toronto

McAndrew, Brian. "Chinese are moving to the suburban 'Asiancourt'," Toronto Star, May 14, 1984. https://tc2.ca/sourcedocs/uploads/images/HD%20Sources%20(text%20thumbs)/Chinese%20Canadian%20History/Attitudes%20toward%20Chinese%20immigration/Attitudes-toward-chinese-immigration%206.pdf

Myseum of Toronto, "Jean Lumb: Toronto Stories." http://www.myseumoftoronto.com/programming/jeanlumb/?gclid=Cj0KCQjw1a6EBhC0ARIsAOiTkrFX9PGhMU6I_Pf6izvlHP7Y_wm180wZsqmJDZI-nCwQiOofUoWLqhMaAiMzEALw_wcB

Ontario Jewish Archives. "Immigration." https://www.ontariojewisharchives.org/Explore/Themed-Topics/Immigration