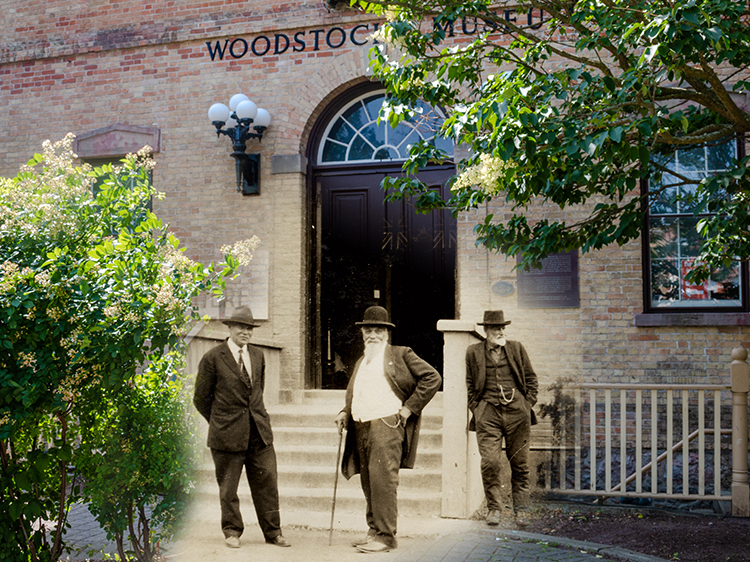

Walking Tour

View from the Hill

Tower Hill

Joshua Edmunds

If you were to wind the clock back several decades, you'd find rural Ontario a place dotted by towers reaching into the sky. These structures were fire towers, and served as lookouts constructed by local forest rangers. In the time before airplanes, these towers were useful for spotting the telltale smoke trails that accompanied a raging wildfire.

On this tour, we will take a trip through Parry Sound history. As we stand atop the Fire Tower, try and reflect on the landscape before you -- and how it has changed and been changed by the people of Parry Sound.

This project is a partnership with the Parry Sound Business Association and the West Parry Sound District Museum.

1. The Fire Towers

West Parry Sound District Museum 1999.126.005

"I think it especially fitting that some memorials such as this should be erected in honor of those forestry pioneers who, long ago, conceived, built and maintained the fire tower network. I refer, of course, to the forest rangers -- that breed of man long since gone, who gave Ontario its first fire protection."

Leo Bernier, Ontario's Minister of Natural Resources, 1975.

The government of Ontario first assumed responsibility for protecting the province's forests in 1917. Integral to this effort was the ability to pinpoint fires in the early stages, before they had the opportunity to grow out of control. Thus, the fire towers were born -- huge structures capable of observing kilometers of land from their vantage point. The old tower has been replaced by the more modern one to facilitate more tourists.

* * *

The old fire tower pictured was erected in 1925. It's thought to have been a one of a kind structure, deliberately built to double as public observatory, and fire tower. As a result it's made of sturdier steel than other examples, and includes a network of stairs and landings inside the structural framework. Previous towers typically just had a ladder--no doubt a precarious way of ascending the tower. Parry Sound's is also distinctive in that it is freestanding. Other towers rely on guidewires for their structural integrity. This makes it much more aesthetically pleasing, and the view from the top is wholly unobstructed. Naturally, such an effort was far more expensive than your standard run-of-the-mill fire tower. It cost a whopping $1,175.3

The detection system the forest rangers used was very simple. Armed with binoculars, a ranger would scan the horizon for any fire sign. If sighted, a coordinate would be marked on a map through use of an azimuth ring and alidade, which enabled compass bearings to be taken from something as simple as a column of smoke on the horizon. On Fire Tower maps, the fire tower occupied the central point, and the alidade pivoted to whichever direction the ranger looked in.

2. Boosting Tourism

Begin climbing the tower and reach this stop on the third landing

Peter McEwen had his own designs for Tower Hill. When McEwen was appointed District Forester of the Ontario Forestry Branch in Parry Sound in 1922, the town was struggling economically. The golden years of the lumber boom had passed as the white pine forests were exhausted. Yet the wildfire threat remained, as the "Great Fire of 1916" had shown: That fire had ravaged half a million acres of forest and killed 223 people.1 It was that fire that prompted the formation of the Parry Sound District McEwen thought with this particular fire tower he could help the community by having it both prevent fires and boost a growing industry.

* * *

"Being a tourist town, we naturally want to attract tourists to this tower in order to get them interested in Forest Protection, and to do this, we have built a stairway within the tower which they are allowed to climb."2

McEwen also convinced the town council to split the cost of a water line to the tower, under the guise that it might be used in firefighting. In 1930, he spent $600 to build the bungalow you see now, which measures 16 by 30 feet. Within the bungalow was a kitchen and living room--luxuries as far as forest ranger bungalows go. His personal touch is everywhere: the cabin is in perfect harmony with the grounds, increasing the natural beauty of the hill.

The tower you are climbing now replaced the early fire tower in 1975.

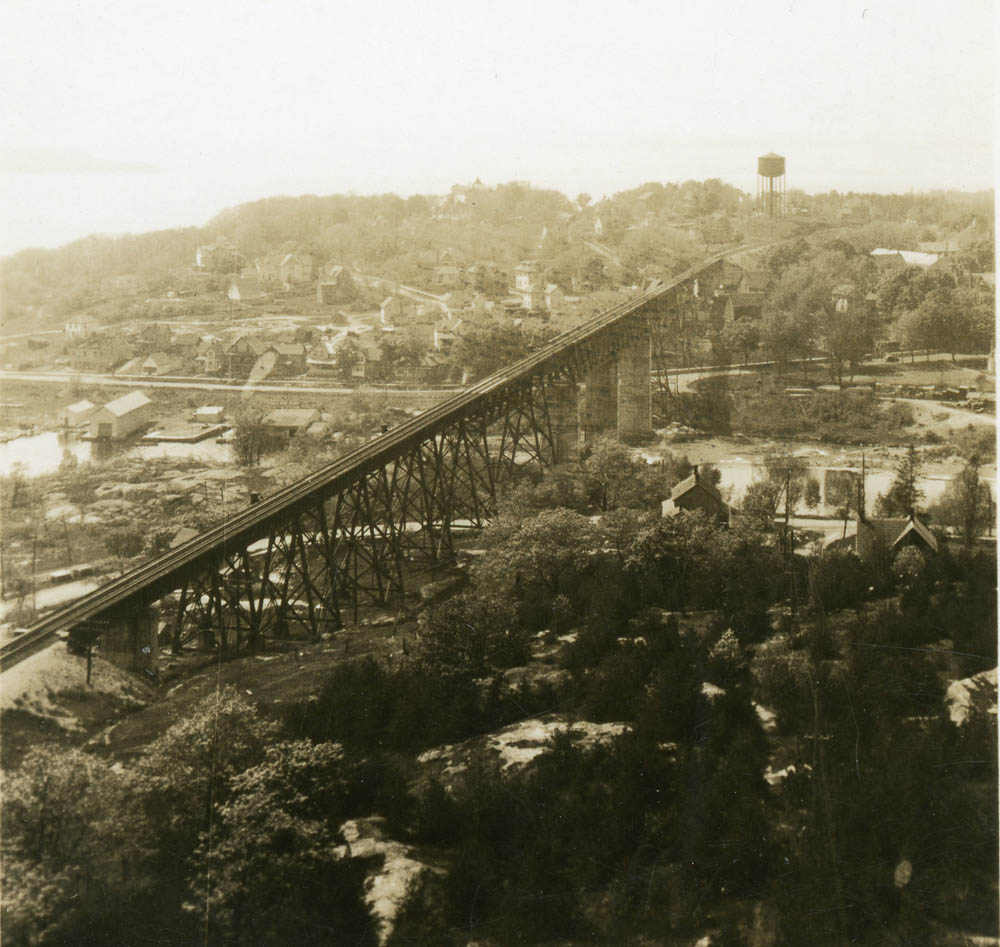

3. Working at a Mill

1936

Climb to the top of the tower to reach this stop

The pioneering lumbermen of Parry Sound relied on the Seguin River. Once trees were felled they were stripped and tossed in the river, then driven downstream towards the mill that once stood at the river's mouth in front of you. for processing into planks. This was dangerous work requiring careful balance and extreme agility. A careless lumberman could easily lose his footing on the bobbing, spinning logs and be carried away with the raging currents, or crushed between the massive trunks.

* * *

"There is usually in a camp plenty of men ready to volunteer; for a man who cuts a key log is looked upon by the rest of the loggers just as a soldier is by his regiment when he has done an act of bravery.

"The man I saw who cut away a log which brought down the whole jam was quite a young fellow, some twenty years of age. He stripped everything save his drawers; a strong rope was placed under his arms and a gang of smart young fellows held the end. The man shook hands with his comrades and quietly walked out on the logs, axe in hand… At any moment, the jam might break of its own accord, and if he cut the key log, unless he instantly got out of the way, he would be crushed by the falling timber.

"There was a dead silence while the keen axe was dropped with force and skill upon the pine log, one or two more blows, and a crack was heard. The men got in all the slack of rope that held the axe-man. Like many others, I rushed to help haul away the poor fellow, but to my great joy I saw him safe on the bank, certainly sadly bruised and bleeding from sundry wounds, but safe."1

4. The Dam Bursts

1936

A short distance up the Seguin River to the north is the Mill Lake Dam. Rebuilt in 1920, it failed catastrophically and burst in April 1921.

* * *

Mayor Hall was confident in Mitchell and Mitchell, and defended their reputation in the North Star. Their lead partner was Charles Hamilton Mitchell, dean of the Faculty of Applied Sciences and Engineering at the University of Toronto. He had had an illustrious reputation, having completed projects in Niagara Falls. His offer was $139,450 to complete the project, which envisioned using an old power generator, in addition to a new one, to churn out the desired 1,400 horsepower.

Early in the construction, there were complaints that work completed was substandard. The North Star was set to putting rumours at rest, pushing out an article with comments from a representative of Mitchell:

"He described the complaints as 'Foolish talk… regarding bad gavel or bad cement.' and furthers that We don't want every Tom, Dick and Harry hanging around, but if any intelligent ratepayer cares to call on us or the engineer we have no doubt he will find the latter gentleman ready to show him all the tests on material that will satisfy anyone that we know our business and are paying attention to it.'"1

Meanwhile, for his successes, Mayor Hall won a second election. By December 1920, Mitchell and Mitchell had still not issued a final certificate on the quality of the concrete work at the dam. Rumours still circulated that it was substandard. Unrelated incidents didn't do much to instill public confidence in the structure's integrity. A month prior, two planks had slipped past the trash gates at the dam's entrance and damaged a turbine's blades. Inspections of the concrete flume had revealed that twenty wheelbarrows of gravel and sand had been worn away from the floor of conduit since commencing operation some five months earlier.

On March 21, 1921, these glaring lapses in quality spelled disaster. A fresh build-up of flood waters, created by snowmelt and an unseasonal heavy rain, caused a 30-foot section of the west-wing wall of the power dam to give way on Cascade Street. Three men at work in the dam made miraculous escapes as water crashed through the concrete structure's doors and windows and swamped the power generators. The consequences, thankfully, were limited: a ruined powerhouse, and a residential home swept away. No deaths occurred.

5. Belvedere Hill

1936

Pictured here is Belvedere Hill, which prominently featured the Belvedere Hotel, built in the late 19th century. From then until 1961, the sumptuous 110 room hotel presided over the "Big Sound" from its commanding vantage point. It was a favourite summer resort for the well-to-do patrons coming from southern Ontario and the United States. The hill also became a popular residential area and the homes there were built with architecturally distinct stone. Yet archaeological finds in the 20th Century raise interesting questions about a dark period in this region's history.

* * *

Jesuit Missionaries were under the protection of the Huron, who were then allied with France. The Iroquois despised Europeans, and particularly loathed the French -- whose missionaries they correctly believed had wrought plagues of influenza and smallpox upon their communities.

Their attacks on Huron and Jesuit settlements were an attempt to force the Europeans from the region. The frequency of these raids, and their ferocity, were hugely successful, and forced the Jesuit Missionaries to abandon the fort of St. Marie in 1649. The surviving missionaries met up with several hundred Huron, who themselves had been forced to flee by Iroquois raids on their lands between Orilla and Midland. This small band of Huron and French created second, more formidable Fort Sainte-Marie on Christian Island.

This was not to last. A cycle of pestilence and famine ravaged the new community at Sainte-Marie. Worse yet, the Iroquois raiders had tracked them to Christian Island. Their attack was carefully timed, striking at the moment when their enemy was weakest. The weakened and dilapidated Huron, unable to resist, succumbed in 1650. At the urging of the Jesuit leader, Father Paul Raguenay, the survivors abandoned Sainte-Marie for Québec.

With the Huron defeated, the Iroquois turned to the Ojibwa, who were also allies of the French. These they punished, stealing their furs which they would later turn to the English for profit. The Ojibwa suffered so much they were themselves forced to leave, with the Iroquois in close pursuit.

The Ojibwa have long since returned, but the echoes of past conflicts still call out from the Hill.

Endnotes

1. The Fire Towers

1. Parry Sound North Star, "Parry Sound fire tower model at the museum", online.

2. Adrian Hayes, Parry Sound Gateway to Northern Ontario, (Natural Heritage Books, 2005).

3. Hayes.

2. Boosting Tourism

1. Hayes.

2. Hayes.

3. Working at a Mill

1. John Macfie, Parry Sound Old Times, (Hay Press, 1996).

4. The Dam Bursts

1. Macfie.

Bibliography

"Parry Sound fire tower model at the museum", Parry Sound North Star. July 4, 2017. Online. https://www.parrysound.com/community-story/7405211-parry-sound-fire-tower-model-at-the-museums/.

Hayes, Adrian. Parry Sound Gateway to Northern Ontario. Natural Heritage Books, 2005.

Macfie, John. Parry Sound Old Times. Hay Press, 1996.