Walking Tour

Parry Sound's Industrial Past

Logging, Mining, and Shipping

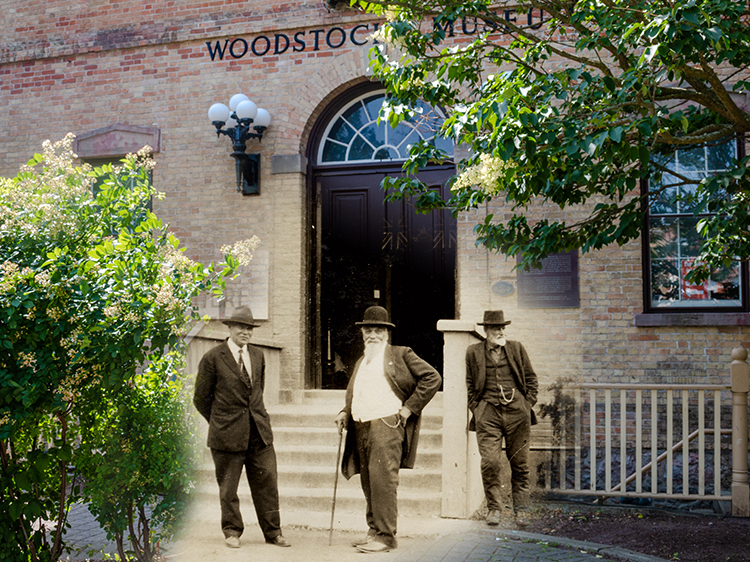

Joshua Edmunds

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1647

On this tour we'll take a walk along Parry Sound's waterfront and learn about the industries that profoundly shaped the town's development.

Parry Sound is located in a protected harbour on Lake Huron's north shore, making it a natural staging area for resource extraction and industrial development in northern Ontario. From the 1850s, lumber mills and mining camps grew up along the coast here, from whence goods were exported by ship.

Georgian Bay was locked in ice for much of the year, effectively cutting Parry Sound off from the outside world over the long winter months. Eventually roads and railways were hacked through the rugged Canadian Shield, ending Parry Sound's seasonal isolation, and further fuelling the growth of a town where the loggers and miners could live.

This tour will examine Parry Sound's fascinating industrial era, when hardy pioneers carved out a living on--what to them--must have seemed the far edge of the world. We'll start at the mouth of the Seguin and see the lumber mills that grew up around this harbour. We'll learn about the terrifying and often deadly risks ships ran in navigating the treacherous waters around Parry Sound. We'll walk along the route of an old railway cut through hard granite, that helped to open this town up to the outside world. Finally at the old Salt Dock we'll see the huge smelter that once stood there.

This project is a partnership with the Parry Sound Business Association and the West Parry Sound District Museum.

1. Navigating the Great Lakes

We're standing now on the Town Dock, which has been first point of arrival for visitors to Parry Sound for much of the town's history. You can see Croswell's Boat Livery on the left, which rented boats for short pleasure cruises (liveries were rental places). Northern Ontario was rugged and impassable in many places, and so the Great Lakes became the highways of Ontario. The vessels that docked here were Parry Sound's lifeline to the outside world.

* * *

As more Europeans settled in the region they set up their own shipbuilding industry and copied techniques they used on their ocean-going vessels, building brigs, sloops or schooners. After 1763 and the conclusion of the Seven Years War, schooners emerged as the preferred type of Great Lake ship for their ability to easily navigate the confined waters and shallow river mouths that characterized the region. In a world of tight river bends and sudden hidden reefs that could appear seemingly out of nowhere, maneuverability was paramount.

It was during the war of 1812 that schooners demonstrated their true value. The Royal Navy and the fledgling American Navy built up small fleets of armed schooners who fought for supremacy over the lakes. There was a shipbuilding rush, and dockyards were expanded to meet the demand. With the end of the war, these dockyards began churning up commercial vessels to explore further west into the lakes.

The age of steam on the Great Lakes began in 1817 with the side-wheelers Ontario and Frontenac. Despite their considerable technological improvements, the adoption of steamboats was slow. Steamers were expensive, and the levels of trade were small. Sidewheelers also had enormous engines, which occupied too much potential cargo space.

The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 created new routes for trade, and allowed ocean-going ships to enter the lakes. The effect was that by 1840 there were more than 100 steamers criss-crossing the lakes. The steamer business had just entered into a golden age of innovation and creativity in steam navigation technology. Vessels grew larger and fulfilled a growing variety of roles. Luxurious sidewheel steamers, such as the beautiful Palace Steamers of the early 1850s emerged, foremost amongst them the 2,000 tonne City of Buffalo. The Buffalo Morning Express said of the ship "The fairy palaces of the imagination were never so gorgeously furnished, nor could the famous barge of Cleopatra, with its silken sails, rival this noblest of steamers."2

Georgian Bay was no longer just the preserve of First Nations bands, European fur traders, and hardy adventurers.

2. The Lumber Mill

West Parry Sound District Museum 1998.166.001

This photo shows the Conger Mill. The mill was owned and operated by the Conger Lumber Company, who had themselves bought it from the Parry Sound Lumber Company, which was Parry Sound's first major industrial enterprise. Working conditions in the mills were arduous and dangerous. Henry Hatherley, a British immigrant who arrived in Parry Sound in 1881, worked in these mills. Writing home to England, he spoke of the tough work conditions:

"As to working in the mill, it is rotten, especially when keeping batch. I am not fond of being amongst the scum of the town and the blackguards of the country, but as things are now there is nothing else for it but being a mill hand."1

The lumber complex pictured here was destroyed by fire on September 21, 1921, which spread rapidly along the shoreline, consuming millions of board feet of piled lumber and many of the buildings you see.

* * *

For cities in Ontario in this period, close proximity to a river was an absolute necessity. A swift-flowing stream was the source of most energy, powering mills that didn't just saw lumber, but ground flour in farming communities.

An abundance of hydropower meant that Parry Sound could process huge amounts of lumber per year. Great swathes of white pine could be felled and floated safely down the riverways towards Parry Harbour, whereupon it could either be processed or tugged to other cities along the Great Lakes. So long as the resource remained, the prosperity of the community was assured. In later years, these rivers would provide integral sources of power in the form of hydroelectricity.

3. The Treacherous Waters

This picture captures a steamer departing Parry Sound. Parry Sound was a major hub for logging exports to southern Ontario, and steamers filled with people and cargo were a common sight during the ice-free months. The lakes were treacherous waterways for sailors, but northern Lake Huron especially so. The region's name--30,000 Islands--could inspire feelings of dread in the most experienced ship's pilots. Adding to sailors' miseries were the storms: Arctic fronts from the north and Warm fronts from the south often collided over Lake Huron, causing sudden catastrophic storms. A single storm in 1913 sank eight ships and sent over 200 sailors to a watery grave at the bottom of Lake Huron.1

* * *

On October 7th, 1895, the Africa, the Severn, and three other vessels set out for Parry Sound to pick up lumber for the Conger Lumber Company. Conditions were optimal until the vessels reached the passage where Lake Huron joined Georgian Bay. What had been southwesterly breeze suddenly veered to the northeast and quickened to a gale. One of the ships, the Severn was buffeted by the tempestuous winds: her masts were torn down one by one, until the ship sat almost helpless in the towering swells. A steam-powered pump was the last hope the ailing Severn had of staying afloat.

At dusk, the Africa took the Severn under tow and the little convoy sought shelter in Boat Cove on Bruce Peninsula. The Severn's steam pump hammered away, and, for a time, seemed to keep the towering waves at bay.

The crew believed the Severn would make it. The Severn, however, missed the entrance to Boat Cove -- instead swinging wide and onto a hidden reef. Exposed, she was quickly overwhelmed by the waves. Her crew could do little more than cling to the rigging and pray for a hasty rescue while the howling winds cut through them like a knife. Fortunately for them, the survivors would be picked up later.

The final fate of the Africa remains a mystery to this day. For a time, she was in sight of the crew of the sunken Severn, but after a half hour had passed she disappeared out of sight. All that remained were empty lifeboats bobbing in the water, and the life-jacketed bodies of two of her crew members -- grim evidence of an abrupt sinking. To the survivors of the Severn, it was clear: the Africa had been lost with all hands.2

4. The Coast Guard Base

Here we see the Parry Sound Coast Guard base, one of the oldest and largest coast guard installations on the Great Lakes. The sprawling islands and hidden reefs of the Georgian Bay posed serious danger to naval traffic. Ships ran aground on a regular basis, prompting the Department of Marine and Fisheries to begin constructing an array of lighthouses throughout the area to help guide ships into Parry Sound. Coast Guard bases serviced these lighthouses, routinely resupplying lighthouse operators, in addition to their usual rescue duties. Built in 1905, this base’s original purpose was logistics for the lighthouse array. However, with the incorporation of the Canadian Coast Guard in 1962, the base’s responsibilities changed from one of simple logistics towards rescue..1

* * *

The vast system of logistics created by the Coast Guard allowed for the maintenance of the lighthouse array. The weekly supply runs undertaken by the Guard ensured that the lighthouse keepers wanted for nothing, which meant that the lighthouses could fulfill their purpose as beacons.2

A century ago the port of Parry Sound was brimming with activity. Ships and steamers of all sizes arrived in Parry Harbour to pick from the lumber stocks that lined the shorefront. Their destinations were as far afield as Duluth, Chicago and Buffalo, and people in the town often eagerly awaited the arrival of these ships and the news they brought.3

The steamer in the foreground was one of the common passenger freights that sailed these waters. Notice the lifeboats that line the upper rails. In the event of a sinking, these boats were the only protection offered to passengers and crew. Should the lifeboats fail to deploy, the unfortunate passengers or crew stood little chance in the frigid waters, as it would often take hours or even days for rescuers to arrive.

The Coast Guard at Parry Sound consisted of the bravest individuals. It takes a rare calibre of person to forgo the comfort and safety of the harbour, and leap into danger. This the Coast Guard did on a regular basis -- placing themselves in the thick of the most dangerous and awe-inspiring storms, so as to rescue the trapped and the stranded.

The ability to operate under extreme pressure, and great risk to life and limb, are job requirements for only a handful of professions. Of these is the Coast Guard. At the Parry Sound Coast Guard base, the bravest kept watch -- prepared to act on a moment's notice.

5. Tragedy of the Waubuno

West Parry Sound District Museum 1999.101.086

This anchor was scavenged from the wreck of the PS Waubuno. Around Parry Sound, the Waubuno holds a legendary status. A wooden sidewheel steamship, she was built in Port Robinson in 1865 and made frequent stops at Parry Sound. Flourishing of trade on Lake Huron in the latter years of the 19th century kept the Waubuno busy bringing a steady stream of people and freight to Parry Sound. Commanded by Captain J. Burkett, the Waubuno sailed from Collingwood on November 22nd 1879, bound for Parry Sound. Along the way, the Waubuno encountered a violent gale and vanished in Georgian Bay with all hands.

* * *

The Waubuno failed to reach Parry Sound. Concerned, on November 24, the tug Millie Grew was dispatched from here in an attempt to locate her. Soon she came across the Waubuno's destroyed hull off of the "The Haystacks", a point five miles northeast of Moose's Point, about halfway from her destination. The wreckage hung in the water in splintered pieces, and her cargo filled the banks of the nearby shoreline.

An investigation followed, and the fate of the vessel was slowly pieced together. The Waubuno's hull lay bottom up in the bay in eleven feet of water, and her entire starboard section was completely destroyed. However, the port side and keel had not a scratch. None of the bodies of the 24 passengers and crew were ever found. Contemporary accounts noted that the engines and boilers were nowhere to be seen -- likely due to the fact that they had broken away from the Waubuno at an earlier point, while the remainder of the wreckage had drifted to its current resting point.

There is no clear evidence as to what caused to sinking of the Waubuno, but this has not stopped a healthy degree of speculation from contemporary accounts. A Captain of the Mary Ann believed that severe winds forced the Waubuno to run broadside of tempestuous waves, whose force pried her apart and caused her to go under. Captain Campbell of the Northern Queen argued that the Waubuno struck one of the rocks off of a group of islands known as the Western Isles. Some posit from the extent of the damage was from nothing nothing less than a hurricane, whose force swept through the Waubuno, claiming her and her crew.

The account of the Captain of the Magnettawan is most compelling. The Magnettawan had left the port of Collingwood shortly after the Waubuno. Her destination was also Parry Sound. While in transit, the Captain was forced to halt at Christian Island due to the sudden onset of the storm. There, he hunkered down while the waves and shrieking gales rocked the vessel. Having experienced the storm, he argued that the Waubuno had probably become trapped out on open water. The captain had probably dropped anchor and tried to wait it out. Instead the ship was torn in half by the storm.

Today, the wreck of the Waubuno lies at its final resting point, submerged in fifteen feet of water.1

6. Industrial Railways

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1567

Pictured here is the Parry Sound Pump House. Built in 1892, the former Parry Sound pump house is the last remaining 19th century building on the shoreline. The building provided not only clean water to the Parry Sound community, but powered the hoses that firemen used to battle fires.

Lying on the Great Lakes, the onset of winter in Parry Sound signalled the start of a period of isolation. No new steamers would be spotted on the horizon until the coming of spring. What this entailed was a period of profound solitude for many inhabitants of the Sound. Without any steamships visiting, the community would be without many newcomers for months. This would only change with the construction of the railways, which would allow for year-round travel.

* * *

The Key Valley Railway line was one particular instance where the challenging terrain of the Canadian Shield could be turned to one's advantage. The Key Valley Railway designed for a railway to cut across their land claim to unlock a vast reserve of white pine. The unique topography of the riverbank along the Key River formed a natural roadway, one which could equally be converted for rail use. To not do so would be to rely upon the alternative of carriage by sleigh to the Canadian National Railway at Mowat.

Building a railway, however, is a hugely expensive endeavour. The tremendous costs and unexpected expenditures involved in building their railway line ended up bankrupting the KVR. Another company by the name of Schroeder Mills and Timber purchased the former KVR assets and completed the line in 1919, which was operated until the exhaustion of white pine resources in 1927.1

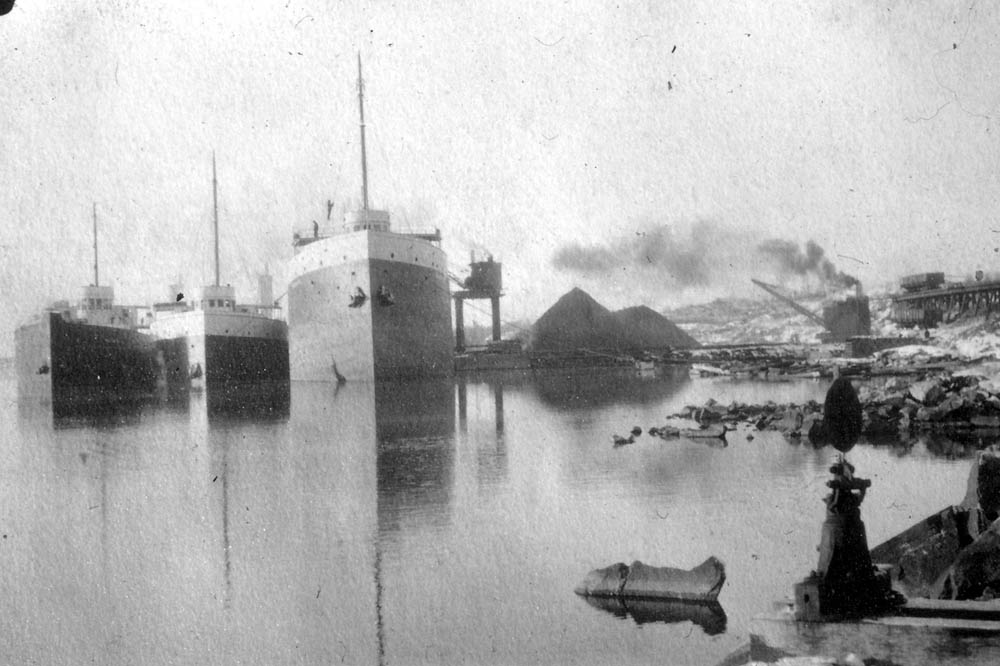

7. Depot Harbour

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1647

1910s

As the industrial yield of Parry Sound diversified, so too did its imports and exports. Pictured here is the Parry Sound dockyard, which exported grain, iron, and coal. The Parry Sound dockyard, and its robust industrial capacity, almost did not come into being. This was due to a spectacular drama which ensued in the late 19th century between the town and a railway tycoon.

* * *

The legislation which governed Canada's First Nations, the Indian Act, at the time allowed for indigenous lands to be taken over by settlers if they wanted to build a railway.

Booth cynically used this legislation to compel the Anishinaabe living on a reserve on Parry Island, just opposite the Town of Parry Sound, to sell their land to him for far less than it was worth. In the end his scheme was nothing short of trespassing and expropriation, lent a thin veneer of legal cover by the Indian Act.

Booth took the land and established a new town: Depot Harbour. Depot Harbour quickly became one of the most prominent ports on the Great Lakes. It served as the shortest route for transporting grain from Northern farms to the Atlantic and beyond.

The surrounding town of Depot Harbour had one hundred and ten homes for workers and residents, as well as two large grain elevators to facilitate the grain exports. Although primarily industrial in nature, the town also had a number of shops and even a hotel for any tourists who might visit. At its height, 1.600 residents called Depot Harbour home, with the number growing to as many as 3,000 during the summer months.

Naturally, the residents of Parry Sound had sold the Parry Sound Colonization Railway with the understanding that Parry Sound was to be its terminus. Booth's actions amounted to nothing less than treachery. Depot Harbour's existence presented a grave threat to their community's future. Efforts to acquire a rail connection were redoubled, and ultimately succeeded with the completion of the Parry Sound Rail Line in 1896. As for Depot Harbour, a combination of the Great Depression and the Parry Sound rail line contributed to its decline and eventual demise. The majority of the community departed during these years, exacerbating its state of disrepair. Without the daily influx of cargo, the end of Depot Harbour's glory days was inevitable. It came during the twilight months of the Second World War, when the partially dismantled grain elevators at Depot Harbour caught fire during preparations for V-J Day. Wafting embers spread to the nearby storage sheds, where a large supply cache of war supplies remained. The ensuing bonfire consumed much of the port. Today if you visit the site of the town, you'll find little evidence that it was ever there.

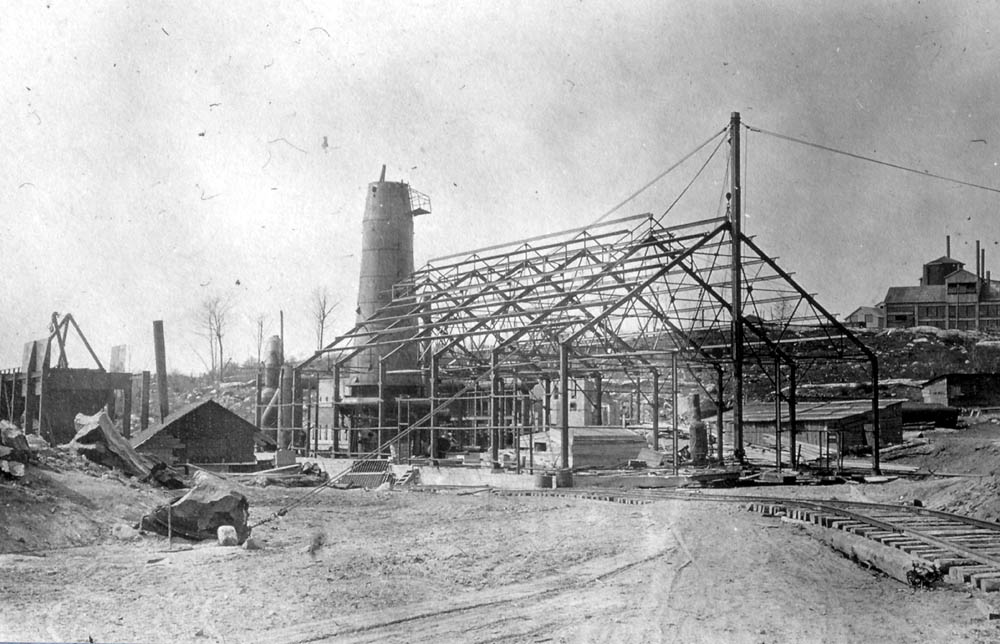

8. Diversifying Industry

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1641

Parry Sound's owes its origins to the logging industry, and was reliant upon its revenues for the first several decades of its history. But residents were always fully aware of their dwindling timber resource. Many wanted to diversify the village's industrial output to ensure long-term prosperity. These smelters processed Northern Ontario iron mines for southern Ontarian use -- serving as vital production centres for the emerging Canadian nation.

* * *

"Instead of waiting to see what will turn up to take the place of the sawmill, steps should be taken toward the establishment of industries that are best suited to a successful growth here. Foremost among the industries which may be said to be indigenous of the soil may be ranked a tannery because the supply of tanbark available is almost inexhaustible and the means of bringing in hides is easy and cheap. A furniture factory would also find an abundance of the finest raw material from which to draw its supplies. No better point could be found for a blast furnace when the railway opens up the iron mines between here and Ottawa. There will also be a good opening for a woolen factory and carding mill, sash, door and planning mill, foundry, cheese factory and a number of minor industries."1

Smelters, factories, and manufacturers were integral for a modern production centre. They offered dependable jobs, and provided a chance for men to break out of the logging-farming cycle that was so characteristic of Northern Ontario employment. Iron was of particular importance. Ontario iron mines found buyers across Canada. Centres like Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal had an insatiable demand for the resource.

But prosperity founded on industrial output was a fickle creature. The industrial output of Parry Sound fluctuated with demand, and reached its apex during the World Wars. For all the community’s enthusiasm about industrial prosperity, such wealth and riches remained surprisingly elusive. What was striking was that although it had been a battle to attract industry and investment in Parry Sound, it was a veritable war to retain it.

Even more surprising, was that the answer to their concerns for long-term prosperity had been staring them in the face the entire time. Tourism. The natural beauty of the Georgian Bay, and the magnificence of the 30,000 Islands region, proved an irresistible lure -- one which Parry Sounders could readily base their economy on.

This transition marked the final shift for the Parry Sound economy, as it outgrew its logging and smelting origins and came into being as a premier tourist destination.

Endnotes

1. Navigating the Great Lakes

1. P. Labadie, B. Agranat & S. Anfinson. Minnesota's Lake Superior Shipwrecks A.D. 1650-1945. (Minnesota Historical Press, 1997), online.

2. Kathryn Monk, The Development of Aboriginal Watercraft in the Great Lakes Region. The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology. (Vol. 7, Issue 1, June 2011), 4 .

2. The Lumber Mill

1. John Macfie. "Some Lofty Views of Parry Sound are lodged in the National Archives." Parry Sound North Star, March 18, 2015. Online.

3. The Treacherous Waters

1. NOAA, "Centennial Anniversary of the Storm of 1913," Online.

2. Adrian Hayes, Parry Sound: Gateway to Northern Ontario, (Natural Heritage Books, 2005), 44.

4. The Coast Guard Base

1. "Canada's Coast Guard Turns 50", Huntsville Forester. Feb. 3, 2012, online.

2. Thomas Appleton, Usque Ad Mare: A History of the Canadian Coast Guard and Marine Services. (Canadian Department of Transport, 1968), 271.

3. Hayes, Parry Sound.

5. Tragedy of the Waubuno

1. Various Authors, "Waubuno (Steamboat) sunk, 21 November 1879." Maritime History of the Great Lakes, Online.

6. Industrial Railways

1. John Macfie. Now and Then. (Georgian Bay Beacon Publishing Company Ltd, 1983).

7. Depot Harbour

1. John Macfie, Parry Sound Old Times, (Hay Press, 1996).

Bibliography

"Canada's Coast Guard Turns 50," Huntsville Forester. Feb. 3, 2012. Online. https://www.muskokaregion.com/news-story/3572403-canada-s-coast-guard-turns-50/

"Centennial Anniversary of the Storm of 1913," NOAA. Online.

Hayes, Adrian. Parry Sound Gateway to Northern Ontario. Natural Heritage Books, 2005.

Labadie, P., Agranat, B., & Anfinson, S. Minnesota's Lake Superior Shipwrecks A.D. 1650-1945. Minnesota Historical Press, 1997. http://www.mnhs.org/places/nationalregister/shipwrecks/mpdf/mpdf2.php.

Macfie, John. Parry Sound: Now and Then. Georgian Bay Beacon Publishing Company Ltd, 1983.

Macfie, John. Parry Sound Old Times. Hay Press, 1996.

Macfie, John. "Some Lofty Views of Parry Sound are lodged in the National Archives." Parry Sound North Star, March 18, 2015. Online.

Monk, Kathryn, The Development of Aboriginal Watercraft in the Great Lakes Region. The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology. Vol. 7, Issue 1, June 2011 .

Various Authors, "Waubuno (Steamboat) sunk, 21 November 1879." Maritime History of the Great Lakes, Online. http://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/56303/data.