Walking Tour

Departure Bay

From Sea to Sky

By Annabel Howard

Nanaimo Community Archives 2005 033 A-P1

This walking tour will cover the fascinating history of Departure Bay, the broad sweep of coast north of Nanaimo.

Important Tour Route Notes

The tour starts at the BC Ferries terminal and involves a walk along the beach of rock and sand, so we recommend you wear appropriate footwear. It includes several historic photos taken from wharves of which only the piers still exist. Be aware that today they can only be reached at low tide. It also ends with a small hike up Sugar Mountain where you will be rewarded with a stunning view of the bay and a remarkable glimpse into the past by seeing the bay through the eyes of photographers who stood atop the mountain over a century ago.

The Village of St’litlup

Departure Bay was for thousands of years the site of the local Snuneymuxw people's winter village. The village was known as St’litlup, or 'The Base of the Mountain.' The Snuneymuxw, whose name translates as 'The Great People', have inhabited these lands since time immemorial. Their territories extend from here to far down the coast of Vancouver Island, and to many islands across the Salish Sea.1

The village itself was inhabited principally by four families, who lived in three rows of cedar longhouses on the beach. There was another set of longhouses near the modern-day Pacific Biological Station.2 As well as a place for rest and ceremony during the cold season, the Snuneymuxw used St’litlup as an ancestral burial ground.

There was ample fish and game to ensure the village's inhabitants had access to a varied diet: In 1992 archaeological excavations of the village identified 30 bird species and 14 types of mammals in their middens.3 St’litlup was also the place where spring food gathering began with the March herring run. The herring were so abundant that schools of the fish chased ashore by whales would pile a foot high on the beaches. This abundance of natural resources gave the bay its nickname: 'The Food Cupboard'.

The Nanaimo coastline was surveyed by the Spanish in the late 1700s, and they named Departure Bay ‘Bocas de Winthuysen' after a Spanish admiral. In the 1850s English representatives of the Hudson's Bay Company who were surveying the area started calling the place Departure Bay.

Around the same time Governor James Douglas signed one of the 14 eponymous Douglas Treaties with the Snuneymuxw. In the negotiations the Snuneymuxw promised to share their land with the settlers, and would retain their village sites, like St’litlup. They also preserved the “liberty to hunt over unoccupied lands” and the right to “carry on their fisheries as formerly.”4 They received 668 blankets in exchange.5

The rights granted by this treaty were ignored by the settlers, who claimed the treaty actually gave them all the land forever. Most of the Douglas Treaties were actually agreed orally, with the First Nations peoples agreeing just to sharing the land. Once this was agreed they were asked to sign blank pieces of paper. When Douglas returned to Victoria he wrote the treaty text himself, and used language to "suggest that the signatories sold their land to the Crown completely and forever."

This was all news to the Indigenous, but when they found out they'd been deceived, they found they had little legal recourse. According to the Te'mexw Treaty Association, even today, 175 years later, "the courts have continued to describe the Douglas Treaties as surrendering part of the territories of the signatories."

Curiously, the Saalequun Treaty that covered the Snuneymuxw, the text was never written in and it has remained blank ever since.

Settler History

The first British settlers arrived in 1861, and they lived alongside the Snuneymuxw in Departure Bay. By the late 1860s, with the discovery of coal, the bay was already becoming industrialized: a railway was built to the coast from the mine at Wellington, and the first wharves and coal docks were constructed. In 1882 Departure Bay was described as a fine and bustling harbour: "adjacent to Nanaimo with accommodation for a whole fleet, and it often contains many vessels some loading coal and others waiting for cargoes."5

Despite the early boom, Departure Bay's population diminished as coal was discovered further south as well as further inland at Wellington. By the late 1800s the area was described as "virtually uninhabited" and remained so until after the Second World War.6

Like Nanaimo itself, Departure Bay began to flourish again in the postwar era. In the 1970s the municipality of Departure Bay was amalgamated into Nanaimo itself. Despite this a distinctive local character and sense of community has been maintained.

In recent years there have been moves to expand the Snuneymuxw territories, which by the start of the 21st Century had been reduced to 266 hectares spread over four small, separate reserves. In 2013 a reconciliation agreement was signed, guaranteeing the Snuneymuxw 877 hectares, including the restoration of an ancestral burial site at Departure Bay.7

This project is possible with the generous support of the Nanaimo Hospitality Association and the Petroglyph Development Group of the Snuneymuxw First Nation. We would also like to thank the Nanaimo Archives and Nanaimo Museum for use of their historic photo collections and providing research assistance.

1. The Ferry Terminal

Nanaimo Community Archives 2013 003 A-P29

1960

This photograph gives a clear idea of how rapidly this coast has been developed since the Second World War. A simple wooden pier sixty years ago, Departure Bay now hosts a sophisticated ferry terminal through which thousands of passengers and cars pass every day.

* * *

It wasn't until 1951 that a ferry terminal in Departure Bay was built by the Black Ball Ferry Company. It ran two ships, the Kahloke and Chinook, across to Horseshoe Bay in West Vancouver. They faced fierce competition from the long established Canadian Pacific Ferries, who had their own terminal on Cameron Island near downtown Nanaimo.

In the late 1950s, when labour disputes disrupted ferry services and largely cut Vancouver Island off from the mainland, the province's premier, WAC Bennett, intervened and established the crown corporation BC Ferries. The new company quickly bought Black Ball's ships and ferry terminals and ran the ferries themselves. They continue to manage it to this day. As you can see by comparing the then and now photos, they've expanded and upgraded the terminal a number of times.

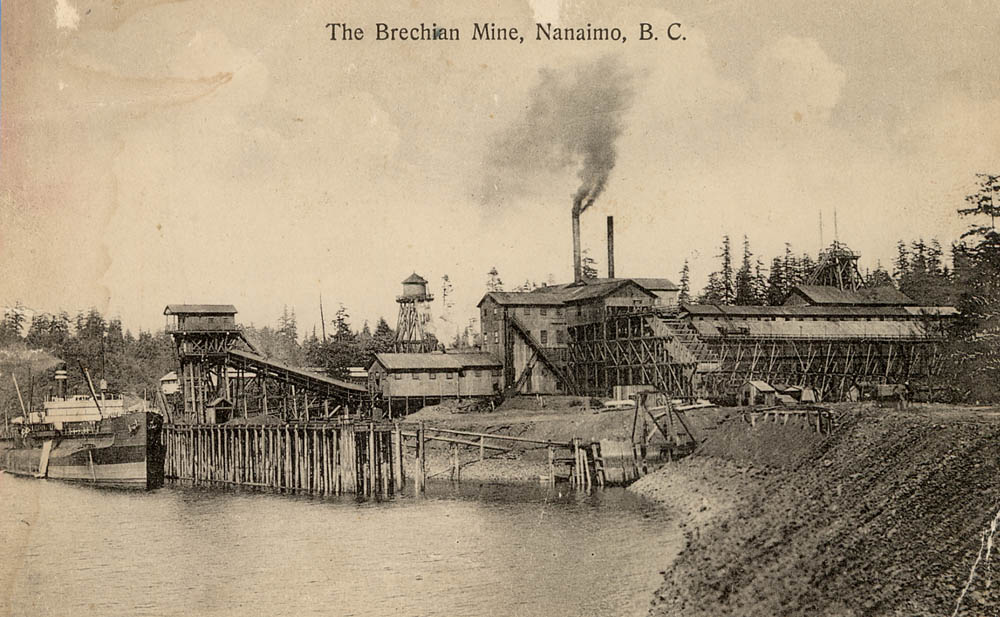

2. The Brechin Mine

1900s

This photograph shows the Brechin Mine, otherwise known as the No. 4 Northfield Mine. The shafts here extracted coal from a seam that ran all the way across the water to the island of Saysutshun. Brechin was one of a number of coal mines in this area that quickly grew to rival the first coal mines around Nanaimo.

* * *

For the next few years the VCC's mining continued to focus on downtown Nanaimo. In 1864 one company brochure boasted about Nanaimo's port: "the harbour has been carefully buoyed, and is available at all tides; and a commodious wharf is nearly completed, giving greater facilities for the loading of ships of deep draught."1 Coal mining there was highly successful, and exports to San Francisco soared from from 5,204 tons in 1861 to 21,345 tons in 1863.2

From the 1870s however, the VCC's dominance of the coal business was tested by competition from the famous industrialist, Robert Dunsmuir. He had made stunning coal discoveries at Wellington, about three kilometres inland from here, and kickstarted a scramble for coal leases around the harbour. We will return to Dunsmuir's pivotal role in the development of Departure Bay later on in this tour.

Brechin, like so many of BC's early mines, derived its name from Scotland, from whence most of the early miners came. The name can likely be traced to the small town of Brechin, on Scotland's stormy east coast. Others claim that the mine was named simply for the bracken that grew so abundantly in the bay. A third theory was that iit was named after 'Brychan'--a Celtic hero--although the Scots would probably have something to say about this, Brychan being Welsh, not Scottish.

Although the Brechin Mine was closed in 1913, its name lives on in the east-west road that connects the No. 1 to the Island Highway.

3. Enjoying the Beach

1920

The men, women and children in this 1920s scene are leisure-seekers enjoying the bay's shallow, warm waters, and sandy beaches. In the distance it is possible to see the local hotel, the old Bay Saloon.

* * *

Families would come from the surrounding areas to take advantage of Departure Bay's long sandy beach. Happy photos like this one can be found in many a Nanaimo family's photo album.

An economic double wallop was just around the corner. In the late 1920s coal demand began to plunge as it was supplanted by oil as the primary fuel of Western civilization. Then came the Great Depression of the 1930s and a devastating collapse in economic activity. Unemployment, poverty and misery ran rampant to an extent almost beyond the imagination of the contemporary reader.

Communities banded together to combat the hard times, and some evidence of that is near where you now stand. The Kinsmen Club sought to soften the blow and held fundraisers to build park amenities and provide free swimming lessons. One of their successes was Kin Park just above the beach here. It wasn't until the 1950s, when the economy began to recover, that a new hut, containing proper changing facilities and bathrooms, was installed.

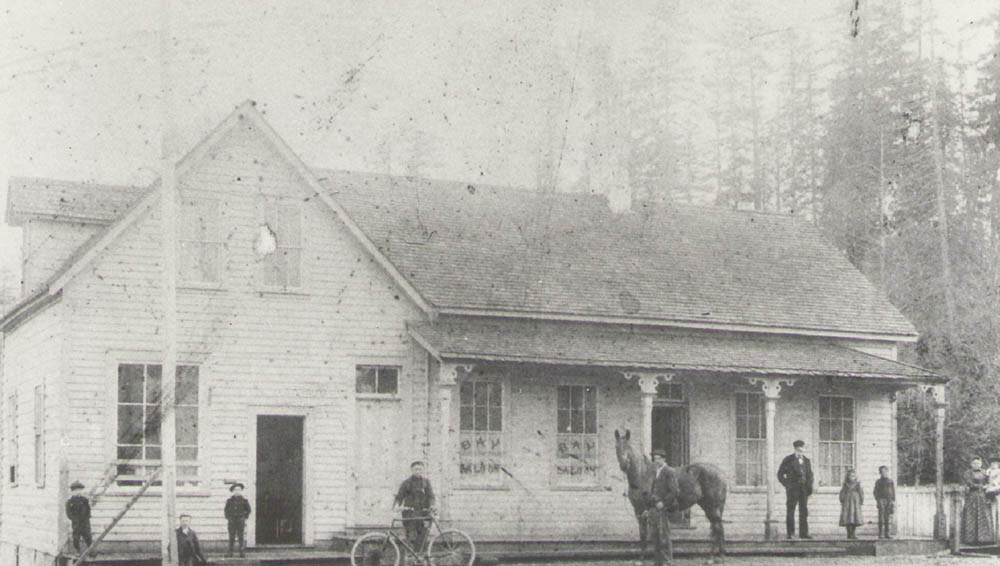

4. Harper's Hotel

Nanaimo Community Archives 1993 028 A-P42

1896

The Harper's Hotel, otherwise known as The Bay Saloon, or simply 'Harper's,' was one of the earliest settler establishments in Nanaimo. It had a rather infamous reputation that was "known by ships all the way to San Francisco."1

* * *

Given the clientele of miners and sailors, it's little surprise Harper's Hotel was a rowdy place. The liquor flowed freely—with or without a liquor license, depending on the changing laws of the day. The patrons enjoyed brawling, firing guns in the air, and stampeding horses down the street. The partying frequently got out of hard, historian Lynne Bowen writes, and "sunrise would often reveal a body lying dead on the beach."2

Harper was a savvy businessman, and quickly realized the value of his real estate. He lived with his family in three rooms in the hotel, but rented out parts of the first floor to serve as a post office, a store, and a bar-dining room. He cut quite a figure in the local community, and the hotel was a focus point for the Departure Bay community until it was demolished in 1941.

5. Hamilton Powder Co.

1903

This 1903 photograph shows the first explosive plant built on the West Coast. It belonged to the Hamilton Powder Company and was the site of Nanaimo's most spectacular explosion.

* * *

Local historian Carole Davidson writes:

"The concussion then set off the gelignite building 400 feet away, where a large quantity of high explosives was stored. Both buildings were wrecked and twelve men were killed. Their bodies were unidentifiable... [The] explosion at the Departure Bay powder works launched a piece of railway track 80 metres through the air with such force that it wrapped itself around a tree... like a corkscrew."1

The blast was so powerful that it shook the windows of houses 60 kilometres away in Vancouver.2

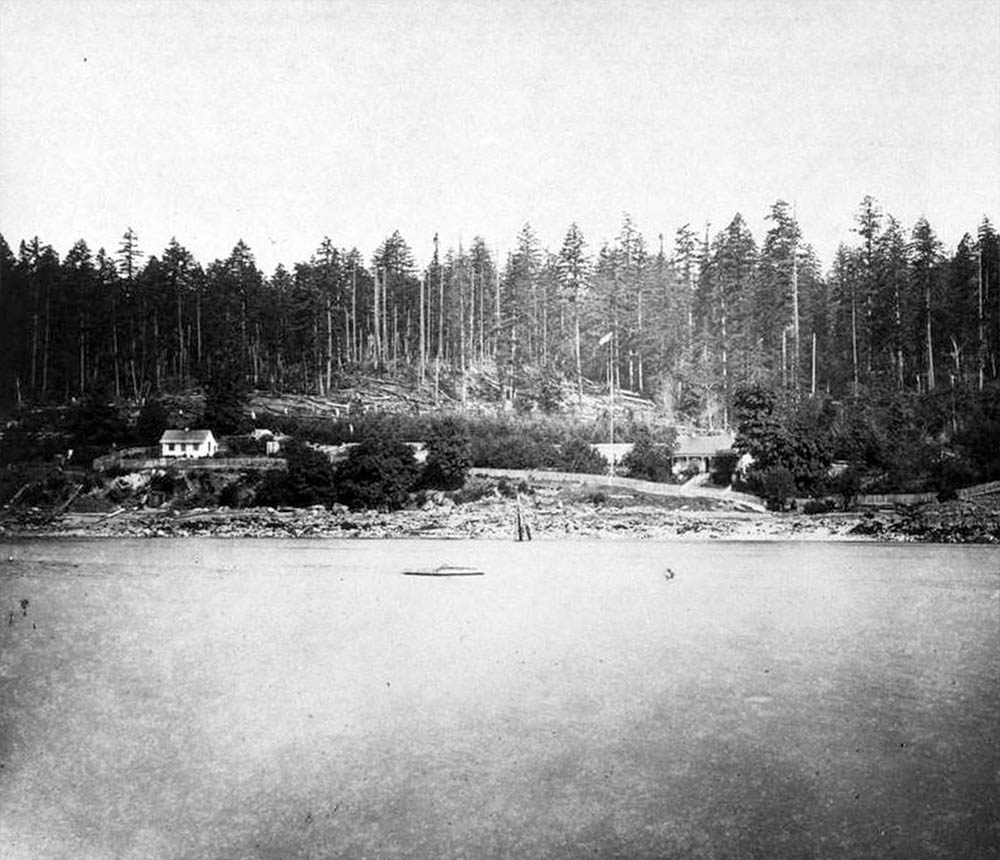

6. The First Homes

1870s

This photograph from the 1870s shows some of the very earliest Departure Bay settler homes. They are nestled between a wild shoreline and the long-departed forest.

* * *

Early settler life was made easier by the abundance of food in Departure Bay, and the generosity of the local First Nations. As noted by Jan Peterson in her book A Place in Time, settlers traded goods like tobacco, beads, shot and biscuits for salmon, herring, deer, clams, and ducks from the Snuneymuxw, and potatoes from the Cowichan and Chemainus peoples.1

7. HMS Boxer

1870s

In the early days of coal mining and export in Departure Bay, a wagon filled with coal can be seen riding along the tracks to the HMS Boxer. This ship played a crucial role in the development of Wellington and Departure Bay's coal industry.

* * *

Dunsmuir set about founding a company through which he could claim the land and begin extraction. In order to do this he had to convince wealthy settlers to invest in his business, and this required him to prove the quality of the coal. He managed to persuade Lieutenant Diggle of the HMS Boxer, first to take a shipment of Wellington coal to Victoria for testing, and then to invest $10,000 in the firm that became Dunsmuir, Diggle, and Company.2 We cover the life of the remarkable Robert Dunsmuir in greater detail in the Robber Baron or Captain of Industry walking tour.

To this day tensions exist around the land that the British Crown granted to Dunsmuir, and which he consequently (and very effectively) exploited for coal. In 2016 a settlement was ratified granting the Snuneymuxw nearly $50 million in compensation for land illegally obtained by the crown in the 1880s.3

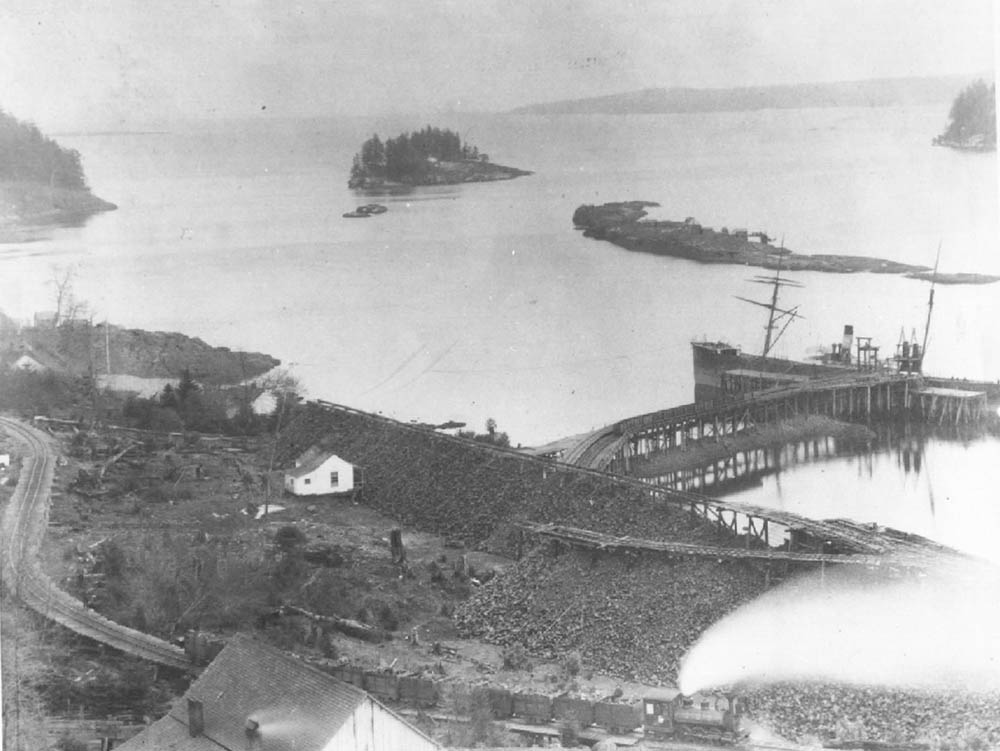

8. The Coal Wharves

1890s

Infrastructure developed very quickly around the coal industry, as can be seen in this photograph of the bay in the 1890s.

* * *

A marker of quite how significant Dunsmuir's business enterprises had become, not only for Nanaimo, but for the whole of British Columbia, is indicated by the fact that the first telephone in British Columbia was installed in his offices in 1875. The phone line ran between the mining operations at Wellington and the loading docks at Departure Bay, pictured here.

Dunsmuir admired the industriousness of Chinese workers and sought many to work in his mines. He could also get away with paying them a lot less than white workers, and their perilous immigration status meant they were far less likely to do things like unionize or demand better or safer working conditions.

In 1885 a Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration reported that while there were only 67 Chinese labourers in Nanaimo, there were 727 living and working at the mines in Wellington.2

9. The Fate of St’litlup

Nanaimo Community Archives 1997 013 A-P1

1939

We can see here that Departure Bay is recovering from the Great Depression. A beach full of bathers. Telegraph poles lining the new roads which, in turn, are lined with new cars. It is sobering to think that only forty years before this the Snuneymuxw were still living in longhouses on this very beach.

* * *

This was a clear violation of the Douglas Treaties, but the new leaders of British Columbia felt little responsibility to honour Douglas's agreements. Although the Snuneymuxw persisted in returning to their traditional territory, they were finally overwhelmed when, at the beginning of the 20th Century, various industrial structures were erected along the shore. These included the Dunsmuir Colliery wharves, the dynamite plant, the Ikeda cannery, and the houses and roads that are so clear in this photograph from 1939.

10. The Peak of Coal

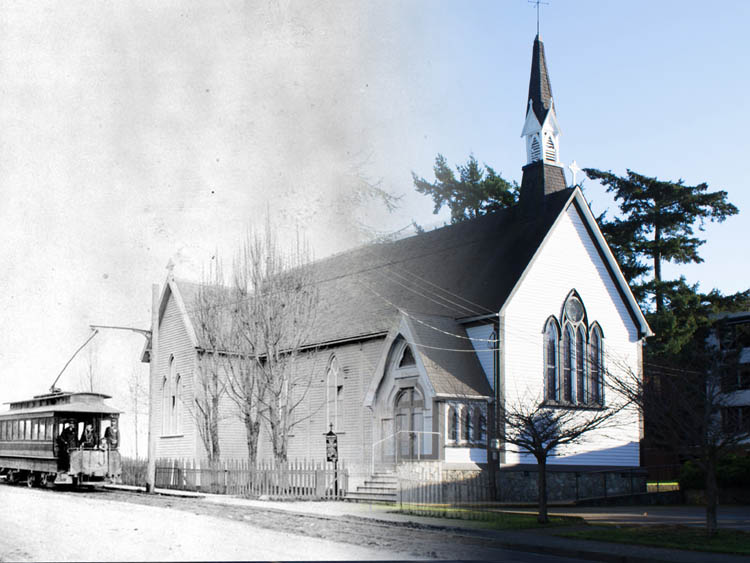

Nanaimo Community Archives 2005 033 A-P1

1890

The many ships we can see docked at the coal wharves in this photo are proof of the productivity of the Wellington mines. However, in the decades after this photo was taken fishing would also come to play an important role in Departure Bay.

* * *

A few years after this photograph was taken, a new industry sprang up when settlers began to exploit one of the natural resources that had originally drawn the Snuneymuxw to Departure Bay: the herring run. In 1896 James Brown started a fishing operation and caught 100 tonnes of fish: the settler's herring fishery was born.

Japanese fishermen with expertise in catching and preserving fish, began to immigrate to Vancouver Island in the late 1800s. By 1896, 452 fishing licenses had been issued to the Nikkei, as the Japanese Canadians were known, they quickly came to dominate the industry, primarily operating out of Saysutshun at what is known as Saltery Beach.

The biggest of all the firms, however, Ikeda & Co., operated out of Departure Bay. Ikeda, which employed exclusively Japanese workers, preserved and exported a sixth of the entire herring catch. In the 1908-9 season, 43,300,000 pounds of herring were caught.2

11. Preserving the Past

Nanaimo Community Archives 1993 028 A-P17

1890

This bird's eye view of Departure Bay shows coal heaped up alongside the wharves. In the foreground a train steams along the newly completed E&N railway. Since the industrialization seen here in the late 19th century, Departure Bay has undergone massive change and is now looking forward to the future.

* * *

It is easier to see the industrial heritage of Departure Bay. By 1900 coal mining here had ceased and moved to nearby Wellington. Over time those mines were exhausted too, and the wharves fell into disrepair. At low tide it is still possible to see the remains of the wharves at the north end of the bay. Remnants of that industrial era are also still visible at the south of the bay, in the explosive plant docks.

Transport remains Departure Bay's main economic focus, and the ferry terminal is the most heavily used of any on Vancouver Island north of Victoria's Swartz Bay.

Perhaps most famously, since 1997 the bay has been the finishing line for Nanaimo's "International World Championship Bathtub Race." It's a 58 km boat race extravaganza conceived by the legendary Nanaimo Mayor Frank Ney, who led the first race (in 1967) dressed in his pirate outfit, and brandishing a sword.

Endnotes

- 1. Jan Peterson, Black Diamond City: Nanaimo - The Victorian Era (Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 202), 9.

- 2. "Snuneymuxw Settlement at Departure Bay," City of Nanaimo, (Online, accessed July 13, 2017), https://www.nanaimo.ca/assets/Departments/Community~Planning/Heritage~Planning/Heritage~News~and~Initiatives/SnuneySettlementSign.pdf.

- 3. Jan Peterson, Black Diamond City: Nanaimo - The Victorian Era. (Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2002), 16.

- 4. "Douglas Treaties," Te'mexw Treaty Association, (online, accessed Nov 26, 2022) https://temexw.org/moderntreaties/douglas-treaties/.

- 5. "Resurrected treaty made history." Snuneymuxw First Nation, January 5, 2015 (Online, accessed July 2017), http://www.snuneymuxw.ca/press-coverage/resurrected-treaty-made-history.

- 6. Jan Peterson, A Place in Time: Nanaimo Chronicles, (Nanaimo, 2008), 92.

- 7. Carol Davidson, Historic Departure Bay: Looking Back, (Victoria: Rendezvous Historical Press, 2006), 25.

- 8. "Resurrected treaty made history." Snuneymuxw First Nation, January 5, 2015 (Online, accessed July 2017), http://www.snuneymuxw.ca/press-coverage/resurrected-treaty-made-history.

2. The Brechin Mine

1. Peterson, A Place in Time, 196.

2. Peterson, A Place in Time, 195.

4. Harper's Hotel

1. "Hotels and Pubs of Nanaimo," transcribed by Dalys Barney, (Vancouver Island University, September 2015, online, accessed July 9, 2017), https://viurrspace.ca/bitstream/handle/10613/197/NanaimoHistoryMcGirr12.pdf?sequence=3.

2. Lynne Bowen, Robert Dunsmuir: Laird of the Mines. (Montreal: XYZ Publishing, 1999), 108.

5. Hamilton Powder Co.

1. Carole Davidson, Historic Departure Bay: Looking Back, (Victoria: Rendezvous Historical Press).

2. "Interview with J.S.Matthews, Dec. 25Th 1957", Vancouver Archives, (Online, accessed July 9, 2017), https://mountpleasantcommunityheritageproject.wordpress.com/2015/06/28/henry-wilfred-maynard/.

6. The First Homes

1. Peterson, A Place in Time, 196.

7. HMS Boxer

1. T.W. Paterson and G. Basque, Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of Vancouver Island, (Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2006), 38.

2. T.W. Paterson and G. Basque, 38.

3. “Snuneymuxw First Nation accepts nearly $50-million settlement over Nanaimo land,” Nanaimo News Now, November 13, 2016 (online, accessed October, 2017).

8. The Coal Wharves

1. "A brief history of Nanaimo Coal," Mid Island News Blog, (Online, accessed July 13, 2017), http://midislandnews.com/early-nanaimo-history/brief-history-nanaimo-coal

2. "Nanaimo Chronicles 1774-2000," City of Nanaimo, (Online, accessed July 28, 2017), http://www.nanaimo.ca/assets/Departments/Community~Planning/Heritage~Planning/Local~History~and~Historic~Resources/NanaimoTimeline.pdf.

10. The Peak of Coal

1. Norman Giney, “From Coal to Forest Products: The Changing Resource Base of Nanaimo,B.C.,” Urban History Review, Numéro 1-78, June 1978, 21.

2. Jan Peterson, Nanaimo: Hub City 1886-1920, (Surrey: Heritage House Publishing Company, 2003), 168.

Bibliography

"A brief history of Nanaimo Coal," Mid Island News Blog. Online, accessed July 13, 2017. http://midislandnews.com/early-nanaimo-history/brief-history-nanaimo-coal

Basque, G. & Paterson, T.W. Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of Vancouver Island. Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2006.

Bowen, Lynne. Robert Dunsmuir: Laird of the Mines.Montreal: XYZ Publishing, 1999.

Bowen, Lynne. Three Dollar Dreams. Lantzville, BC: Oolichan Books, 1987.

Davidson, Carole. Historic Departure Bay: Looking Bay. Victoria, BC: Rendezvous Historic Press, 2006.

Gidney, Norman. "From Coal to Forest Products: The Changing resource base of Nanaimo BC," Urban History Review, Numéro 1-78, June 1978.

"Hotels and Pubs of Nanaimo," transcribed by Dalys Barney. Vancouver Island University, September 2015. Online, accessed July 9, 2017, https://viurrspace.ca/bitstream/handle/10613/197/NanaimoHistoryMcGirr12.pdf?sequence=3.

"Interview with J.S.Matthews, Dec. 25Th 1957", Vancouver Archives. Online, accessed July 9, 2017, https://mountpleasantcommunityheritageproject.wordpress.com/2015/06/28/henry-wilfred-maynard/.

"Nanaimo Chronicles 1774-2000," City of Nanaimo. Online. accessed July 28, 2017, http://www.nanaimo.ca/assets/Departments/Community~Planning/Heritage~Planning/Local~History~and~Historic~Resources/NanaimoTimeline.pdf.

Peterson, Jan. A Place in Time: Nanaimo Chronicles. Nanaimo, 2008.

Peterson, Jan. Black Diamond City: Nanaimo in the Victorian Era. Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2002.

Peterson, Jan. Harbour City: Nanaimo 1920-1967. Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2005.

Peterson, Jan. Hub City: Nanaimo 1886-1920.Surrey: Heritage House Publishing, 2003.

"Snuneymuxw Settlement at Departure Bay," City of Nanaimo. Online. Accessed July 13, 2017, https://www.nanaimo.ca/assets/Departments/Community~Planning/Heritage~Planning/Heritage~News~and~Initiatives/SnuneySettlementSign.pdf.