Walking Tour

Locked in the Citadel

Halifax's Internment Camp

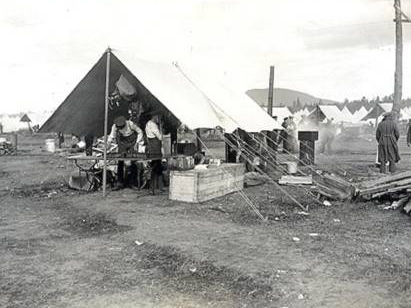

Andrew Farris

Notman Studio Nova Scotia Archives 1983-310 number 6981 / negative: N-9923

The Citadel that overlooks Halifax's harbour was the site of an internment camp during the First World War. Of the 24 such camps that were established across Canada during this time, this was the one that was most like a traditional prisoner of war (POW) camp. Most of those interned here were German and Austrian sailors who had been apprehended at sea by the Royal Navy and brought to Halifax. There were also a number of internees who were immigrants to Canada but had been born in an enemy country and now found themselves designated as enemy aliens and interned for alleged disloyalty or treachery. In the two years of the camp's operation, the isolation of the prisoners was near total, and some were driven to the point of madness by it.

This tour will begin with Halifax's military history and an exploration of why this citadel and this city are here in the first place. We will then jump forward to the First World War, to examine the role that this port and citadel played in the war effort, and the factors that led to the internment of men here. We will then finally look at the stultifying and claustrophobic conditions experienced by the 253 internees in the Citadel.

Route

We will start walking the grounds outside of the Citadel and then move through the gate into the courtyard to see the Cavalier Block where the prisoners were housed (and which today is home to an excellent military museum). Finally, we'll walk the rampart and enjoy views that were long denied to the internees.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. Halifax's Raison d'être

Notman Studio Nova Scotia Archives 1983-310 number 71433 / negative: N-4434

ca. 1892

This wonderful early photo of Halifax was taken from the grounds of the Citadel looking north towards the naval yards. Those naval yards are still there today, and Halifax is the homeport of Canada's Atlantic fleet. There is a good chance that if you are standing on this spot today, you can see some of the Halifax-class frigates or Kingston-class coastal defence vessels, which form the backbone of Canada's navy. The ship whose superstructure appears in the above "now" photo is the MV Asterix, a Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) supply vessel.

These naval yards furnish an explanation for why Halifax exists today. In 1749, the British founded this settlement as a naval base and supply centre that could contest French control of Canada's eastern seaboard. As soon as they arrived, they built the Citadel to dominate the harbour from a great height and protect Halifax from assault on the landward side.

The history of Halifax is relatively unique in Canada in that the city was founded primarily upon military-strategic grounds. The site was well chosen. In the last 250 years, the port's strategic location has helped it play a critical—some would argue occasionally decisive—role in the Seven Years' War, the American Revolution, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, and the two world wars.

* * *

These naval yards furnish an explanation for why Halifax exists today. In 1749, the British founded this settlement as a naval base and supply centre that could contest French control of Canada's eastern seaboard. As soon as they arrived, they built the Citadel to dominate the harbour from a great height and protect Halifax from assault on the landward side.

The history of Halifax is relatively unique in Canada in that the city was founded primarily upon military-strategic grounds. The site was well chosen. In the last 250 years, the port's strategic location has helped it play a critical—some would argue occasionally decisive—role in the Seven Years' War, the American Revolution, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, and the two world wars.

2. The Citadel(s)

Notman Studio Nova Scotia Archives 1983-310 number 6981 / negative: N-9923

ca. 1890s

This photo from the end of the 19th century shows British artillerymen in front of the Citadel loading their field guns to fire a salute. The fort visible behind them is the same fort that exists today and the fourth to be built on this spot. The first was little more than a wooden palisade, part of a network of five forts and city walls built around Halifax in the 1750s to protect from Mi'kmaq raids.

The second and third citadels were built shortly thereafter, as Britain sought to rapidly scale up Halifax's defences during the American Revolution and then again during the French Revolutionary Wars. Construction of the fourth citadel, which still stands today, was prompted by fears of American invasion. If Americans were to seize Halifax, they could cut Canada off from British support and make its defence impossible.

The fourth citadel was built over a 28-year period starting in 1828, and it was far larger than its predecessors. It represented the peak of star fort design, an art and science that had been evolving since the introduction of gunpowder and cannons in Europe in the 15th century, and which culminated in the mid-19th century.

The concept behind star forts is not difficult to grasp. Cannons had rendered the walled castles of the Middle Ages obsolete. In response, castles were sunk into the ground and surrounded by gently sloping walls of earth that could easily absorb the blows from cannon balls. They were shaped like stars so that attacking troops could be raked by fire from multiple directions.

* * *

Cornwallis described the first citadel in a letter:

"The Square at the top of the Hill is finished. These squares are done with double picquets, each picquet ten foot long and six inches thick. They likewise clear a Space of 30 feet without the Line and throw up the Trees by way of Barricade. When this work is completed I shall think the Town as secure against Indians as if it was regularly fortify'd."1

The Mi'kmaq and Acadian threat to Halifax was serious. In one raid, Cornwallis' own son was killed and scalped. Nevertheless, the British won a series of victories over the Acadians and the Mi'kmaq across the region, and the threat to Halifax gradually subsided.

It wasn't until 1776, when Britain's Thirteen Colonies to the south were in open rebellion, that the British felt the need to establish a more permanent and imposing citadel here that would be capable of withstanding American invasion. They mounted 72 guns behind earthen redans and in a central blockhouse, making the fort impervious to all but the most determined and overwhelming assault. The British maintained a massive military presence in Halifax as they fought to crush the nearby American Revolution. Some historians argue that this military presence was a big part of the reason that Nova Scotia—the Fourteenth Colony—didn't rebel and join the other Thirteen.

After the British lost that war, they were quickly confronted by another war with France, and with the loss of the Thirteen Colonies, Halifax became deeply important to the British Empire. The second citadel was dismantled and a third one was built in its stead. It was larger, roughly the size and shape of the current citadel, although it was made of earth rather than stone. At this time, the Town Clock (located just behind where you are now standing) was also built.

The British won that series of wars with France and fought off a number of American attempts to seize Canada during the War of 1812. Afterwards, they turned their attention to building a new and even more impregnable and expensive citadel.

The fourth citadel was made of stone and surrounded by ditches. It was designed in the shape of a star to allow defenders to trap assaulting troops with fire from multiple directions. Anyone trying to cross the ditches could be caught by devastating enfilade fire (fire from the side). T-shaped tunnels radiated out from the fort and could be filled with dynamite and detonated under waves of attackers. The new citadel's artillery complement was greatly enhanced, and new, heavier, and more accurate long-range guns could sink ships far out in the harbour while remaining impervious to return fire.

At the centre of the fort, a barracks was built to house the garrison, which was drawn from the 78th Highland Regiment. It was called the Cavalier Block, and during the First World War, it was where the internees were housed.

3. The First Battle of the Atlantic

W.R. MacAskill Nova Scotia Archives 1987-453 no. 2630

ca. 1932

This image shows the Town Clock, which was built at the start of the 1800s. Beyond it is the harbour, today obscured by proliferating high-rise buildings.

Halifax's harbour remained critical in the British Empire's next major war: the First World War. In the decades leading up to this global conflict, the British gradually ceded control of Halifax's military facilities to the Canadian government, although when war broke out, British warships were rebased in this port. Those ships then ranged out into the Atlantic and down south to the Caribbean to hunt for German merchantmen, commerce raiders, and U-boats. If they captured German ships, the crews were often interned here. As Roger Marsters writes in his study of the internment camp at the Citadel, "Internment operations in Halifax were part of a broader effort to dismantle German naval power and overseas empire in the Atlantic basin."1

* * *

When war broke out in 1914, Canada's navy base in Halifax consisted of one ship: the HMCS Niobe, an older Diadem-class cruiser bought from the British. The Niobe, it goes without saying, was unable to control the northwest Atlantic on its own. The Royal Navy quickly returned to Halifax, where it could project power and protect the merchantmen bringing vital troops and supplies to Britain.

As a naval power, Britain's strategy was to dominate the seas and strangle Germany's global trade. In the leadup to the war, the two powers were engaged in a frantic naval arms race. The Second Reich was a rapidly rising industrial power and sought to challenge Britain's hegemony over the world's oceans. Germany also needed to protect its rapidly growing merchant fleet, which connected the German Empire to the highly globalised world economy of 1914. The German merchant fleet was over 5 million gross tonnes, the second largest in the world. Yet it paled in comparison to the British Empire's merchant marine, which weighed in at over 20 million gross tonnes—itself accounting for almost half of the commercial shipping on earth.2

For both powers, these merchant trade networks represented a huge weakness. If one side could interdict the other's, it would have disastrous consequences for that power's ability to prosecute a war.

By 1914, Germany's naval building programs had not even come close to furnishing a navy that could contest the Atlantic. Germany's High Seas Fleet remained bottled up in the Baltic Sea for the duration of the war. This gave the British free rein to blockade Germany and seize her merchant vessels wherever they could be found. Eventually, the blockade would have catastrophic results for Germany, which by 1916 was already facing famine. It is thought that by the end of the war, as many as 800,000 Germans died of starvation or illnesses brought on by malnutrition.3

In addition to denying Germany its ships and the supplies that they carried, the British also wanted to deny Germany trained sailors. German sailors on merchant ships were usually reservists in the Kaiser's navy, and when war broke out, they were called home to take stations on warships. Many of those ships immediately raced for home, and the British Royal Navy moved to stop them, seizing every German sailor (including those on neutral vessels) that they could lay their hands on.

What was done with these sailors once they had been captured? Many of them were brought to the Citadel.

4. Seized at Sea

Nova Scotia Archives MG 23 vol. 22 no. 14A: Halifax Rifles Book no. 13

1940

In this photo, a unit of the Halifax Rifles marches out of the Citadel during the Second World War. During the First World War, most of the internees housed at the Citadel were German sailors who had been seized overseas. They were prisoners of war according to the legal definition, unlike those in other camps in Canada where the Canadian government struggled to find a passable legal justification for classifying interned civilian immigrants as prisoners of war.

Many of these sailors were seized on German merchant vessels, but the Royal Navy also had a habit of stopping and searching neutral vessels and arresting any German (or sometimes Austrian) reservists that they found aboard. Another group of internees came from the crew of the German auxiliary cruiser Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse.

As Marsters writes about the prisoners taken at sea, the "biographies of internees detained at Halifax… offer a remarkable snapshot of a highly mobile, interconnected world suddenly disrupted by the outbreak of war."1

* * *

In the leadup to war, the outgunned German navy devised creative solutions for getting to grips with British merchant shipping. One of these schemes, the U-boat, almost succeeded in bringing the Allies to their knees in 1917. Another more quixotic scheme was the auxiliary cruiser. A regular merchant or passenger ship would be secretly equipped with guns. They would then sail alongside unsuspecting Allied merchantmen, reveal their weapons, and demand the crew abandon their ship so it could be blown up.

In 1914, expecting that war was imminent, Germany sent a number of these auxiliary cruisers to sea, including the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. When the state of war became official, the cruisers received orders by radio and began sinking Allied ships. The Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse managed to sink two freighters before it was caught by the cruiser HMS Highflyer in Spanish waters. The former passenger liner was slower than the Highflyer, totally outgunned, and completely unarmoured. Yet she managed to exchange fire until she ran out of ammunition, at which point she tried to make a break for it. This proved futile, and the order was given to scuttle the ship. Her crew were picked up and brought to Halifax.

Another group of internees came from a shore party sent to Mexico by the German light cruiser SMS Dresden. As the Mexican Revolution embroiled the country, the shore party had the duty of reaching the German embassy in Mexico City and securing secret German assets. They succeeded and were returning to Europe on a neutral ship when they were stopped and arrested by a British warship.

Also seized at sea in this manner were "large numbers of German businessmen, migrants, and settlers resident in Central and South America [who] were captured and carried to Halifax in consequence of their former military service or reserve status."2

One example of this was internee Andreas Fahr, who had been born in Hamburg and had lived in the US and then Guatemala for 10 years while working in business. Another, Wilhelm Carnap, was a salesman for a silk manufacturer and had spent a decade travelling widely across the Asia-Pacific and the United States. Wally Velte was the 1914 equivalent of a backpacker taking a gap year, and is someone who would be familiar to many young people today. He had completed his studies in music in Germany and had joined a merchant crew so that he could see the world. Instead, he was to spend the war behind Canadian barbed wire.3

5. Enemy Aliens in the Maritimes

Notman Studio Nova Scotia Archives 1983-310 number 12662

ca. 1890s

In this photo, guards stand before the gate of the imposing stone Citadel. When Canada entered the war, there were hundreds of thousands of German- and Austro-Hungarian-born immigrants living in the country. A number of them had been trained as reservists in the armed forces of their homelands. Thus, any who were caught trying to return to their Fatherlands to fight in the war were arrested and interned—and many were sent to the Citadel.

Simultaneously, Canada was swept up in a wave of mass hysteria about potential spies and saboteurs amongst the immigrant population. The War Measures Act reclassified anyone born in an enemy nation as an "enemy alien" and severely curtailed their civil rights. Any whose loyalties were deemed suspect were interned too, even if they weren't reservists and were following regulations.

The legal boundaries around who could be interned were continually expanded throughout the war, sweeping up more and more people on increasingly arbitrary and cruel grounds. In the end, most of the victims of Canada's internment operations were Ukrainians who had been born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Their stories are covered in great detail in tours at other camps across the rest of Canada. In Halifax, however, most of the internees who were Canadian-resident "enemy aliens" were either reservists in enemy armies or accused of disloyalty to Canada.

* * *

The headquarters of Military District No. 6, which covered the maritimes, was located at the Citadel, and from the outset it was inundated with reports of suspicious behaviour by "enemy aliens". At Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, the chief of police reported that the people of the town had convinced themselves that three German residents were planning to attack the merchant ships there. He requested that these immigrants be interned with the reasoning that they'd be safer in an internment camp than at risk of mob violence.2

A paranoid letter came from someone in Falmouth who claimed that a man named Lunstrum owned a small island off the coast. Presumably because of his German sounding name, the letter writer thought that Lunstrum was conspiring to use his island to set up "an enemy wireless station or an advance base for invasion." They concluded "we do not know who to trust."3

There were also reports of miners in Stellarton, Sydney, and Inverness, Nova Scotia, refusing to work alongside enemy alien miners and demanding their dismissal and internment. These people may have been inspired by the miners in Fernie, British Columbia, whose threat to strike resulted in the illegal mass internment of the enemy alien miners there.

The prevailing notions of nationality and subjecthood put the enemy aliens in an impossible position. Essentially, under this model of thought, birth was the prime determinant of one's identity, and that could not be renounced or changed. If one was born in Germany, they were a subject of the Kaiser forever, even if they had moved to Canada as a child and felt no personal or cultural connection to Germany whatsoever. Similarly, Britain would not recognize them as a loyal subject of the empire, often even if they received naturalized Canadian citizenship. National citizenship was a subordinate category to being the subject of a monarch, which was permanent.

Thus, Canadian citizenship and decades of life in Canada were no protection from classification as an enemy alien. The German government also felt entitled to the service of all of the Kaiser's subjects, and demanded that they return to Germany and fight whether or not they wanted to.

Eithel Fritz Vidal of Denmark, Nova Scotia, a German-born naturalized Canadian citizen, discovered all of this the hard way. He wrote to the German consul asking for clarification on that government's position. Merely asking this question, however, was considered grounds enough by the Canadian government for him to be arrested and interned.4

6. The Camp in the Citadel

Nova Scotia Archives MG 23 vol. 22 no. 14A: Halifax Rifles Book no. 13

1940

As one of the few active military facilities in Canada in 1914, the Citadel was an obvious choice to hold internees. The Citadel's internment camp went on to operate for two years starting that October.

In addition, Melville Island (a misnomer for a small, rocky peninsula south of Halifax) also served as an internment camp from September 1914 until January 1915, a role it had previously fulfilled in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. In 1916, the Citadel's remaining internees were transferred to a purpose-built camp established at Amherst, which would remain in operation for almost a year after the end of the war.

In total, 253 internees passed through the Citadel, including 195 Germans, 25 Austrians, 4 Turks, and 29 classified as "Other". Of those, 161 were sailors captured at sea, and a further 51 were enemy aliens living in Canada before the war. There were also 26 internees who were captured in transit.1

* * *

The camp constituted only part of the Citadel, which was itself an active military facility. It was a key part of Halifax's defences in case of naval attack, and it housed a crucial signalling station. As a result, the internees were hemmed into a cramped section of the facility and slept 11 to a room. They were surrounded by barbed wire fences and bright illumination. Guards with loaded rifles patrolled the perimeter. The guards were provided by a Composite Battalion of the militia that drew from all three maritime provinces.3

There were two things that made the Halifax Citadel camp distinctive from the 24 or so other internment camps and receiving stations set up during the war.

The first was the composition of the inmates. As Marsters writes:

"Overall, internees in Canada were most often migrants or naturalized settlers born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire or in Germany, who were Canadian residents at the outbreak of the war, and who were subsequently interned as enemy aliens. In Military District 6 [Maritimes] internees were statistically more likely to be ethnic Germans resident in Germany itself, in Central or South America, or they were working at sea at the outbreak of the war. Most were captured outside of Canada itself, often in the course of military operations, and interned as members of Germany's armed forces reserve."4

The second distinctive aspect was the Citadel's military importance and resulting high security. Halifax and its port were one of the most important military bases in Canada, and the closest to the actual war—in 1918 U-156 managed to sink 23 ships in Nova Scotia waters from the Bay of Fundy to Cape Breton, including the tanker Luz Blanca just 55 kilometres south of where you now stand.5 This combined with the Citadel's status as an important military facility where highly sensitive operations took place meant that security precautions were necessarily intense.

As we will see, these precautions had serious ramifications for the lives of the internees.

7. Denounced as Spies

Nova Scotia Archives MG 23 vol. 22 no. 14A: Halifax Rifles Book no. 13

1940

This photo shows a military band at attention in front of the Cavalier Block (right), which housed the internees. One particularly tragic group of internees kept at the Citadel were those "enemy aliens" who had dared to enlist in Canada's armed forces. Some were able to get past initial screenings and got as far as training camps in England before they were denounced as enemy aliens. These Canadian soldiers were then arrested and returned to Canada in chains. Twenty-three of them were interned at the Citadel.1

* * *

These men's stories illustrate the unfairness of their circumstances.

Some, like Charles Korthaus, enlisted out of genuine patriotic enthusiasm. He had been born in Hamburg, but his parents were English, and they soon returned with the young Charles to England, where he was schooled. The family then immigrated to London, Ontario. Korthaus couldn't even speak German and was a genuine British patriot (the concept of Canadian patriotism had yet to develop at that point). It seemed perfectly natural for him to join up with his friends to fight for King and Empire, and he enlisted with the 9th Mississauga Horse. Yet he had relatives in the German Army and had been born in Germany, making him a subject of the Kaiser rather than King George V. The other soldiers in his unit reported him for being an enemy alien.2

Another absurd episode concerned Therkild Therkildsen. In 1914, men like him were desperately needed by the Canadian Army, as he was one of very few men in the country who had military experience—he had served in the Danish Army as a non-commissioned officer (NCO). He was Danish, not German. Nevertheless, someone noticed that he could read German, and that was enough for him to be denounced as a spy.3

In other cases, people like H. Czaajowski, a Ukrainian man, enlisted because there were no jobs in the west. Yet these men were then ruthlessly teased and hazed by their comrades before being denounced, arrested, and interned. The intelligence officer who interviewed Czaajowski said that he wanted "to return to Canada, as he feels quite miserable with the Canadians [in his unit] who do not treat him well."4

As historian Bohdan S. Kordan writes, these men were marched through the streets of Liverpool by an armed guard with bayonets at the ready, "where the local population denounced them as spies and encouraged the escorts to kill them."5 It must have been a deeply humiliating experience. They were then sent to the Citadel for internment.

Not all internees were doomed to stay here for years. Therkildsen spent four months sleeping on a floor mattress in the freezing Citadel before the Danish consul succeeded in persuading the Canadian authorities that he was not an enemy alien after all.

8. Isolation

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

ca. 1916

This photo shows a view of the Cavalier Block when it served as the main habitation block for the internees. A number of men lounge on the second floor balcony as others pace inside the wire, which was the only physical activity to which they were entitled.

The internees at the Citadel lived in extreme isolation and under a regime of military discipline and security that surpassed most other internment stations. The fact that the internment camp was inside an active military facility meant that camp authorities were reluctant to ever let the internees out of their tiny barbed wire enclosure for any reason. The years of strictly enforced boredom and rigid routine took a serious toll on their mental health.

* * *

Contact with the outside world was limited as much as possible. Prisoners were forbidden from speaking to anyone but guards or other prisoners. Letters were heavily censored and limited to two a week. Any publications containing news about what was happening in the outside world were forbidden (although this regulation was later slightly relaxed). Once a month, the internees were allowed a 15 minute visit, but only if the conversations they had were in English. One wonders who in Halifax would visit the German sailors.1

There was basically nothing for the internees to do but wait for the war to end. The prisoners begged for exercise facilities, which, according to government regulations, were required. Security concerns trumped all, however. A plan to set up a recreation ground on the roof of the Cavalier Block (the only place where there was space for one in the tiny enclosure) was scotched because the prisoners might be able to see the harbour and count the ships.2

The Nova Scotia Automobile Association requested the Citadel's internees for their road building projects, taking note of how internees in the rest of Canada were being used for forced labour. The request was denied. The risk of escape was thought to be too great for these internees, who had been deemed dangerous. After all, they were for the most part actual prisoners of war and not Ukrainian civilians who were interned for being unemployed or homeless.

Based upon what we now know of the conditions in forced labour camps across Canada, we can consider it lucky that the Citadel's inmates did not have to go through that ordeal. Yet the boredom of the Citadel produced its own challenges.

Max Weirauch, a metallurgical engineer, pleaded with the camp's intelligence officer "to get some work for me, because I cannot endure to be for more time without anything to do. I should gladly and without conditions accept the simplest work."3

9. Discipline and Escape

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

ca. 1916

This image shows a garrison unit outside of the Cavalier Block. Unlike more remote internment camps, the Citadel was close to active military operations and therefore also close to the attentions of senior commanders and to the prying eyes of the public. This generally meant that the guards adhered to military regulations, and there are apparently no reports of cruelty or torture occurring here. Nevertheless, sanctioned punishments were meted out to those who showed insubordination or tried to escape.

Since the prisoners had so much time on their hands—almost to the point of driving them mad—it is no surprise that there were some breathtaking escape attempts.

* * *

In camps such as Banff, Kapuskasing, and Spirit Lake, the internees were forced to work in appalling conditions and threatened with being shot if they refused. Yet it makes sense that punishments would be less frequent and severe at the closely monitored Citadel. The defining fact of life for these prisoners was instead boredom.

After one escape attempt, the prisoners wrote a letter to the commandant explaining how future escape attempts could be avoided: "a spacious and attentive place, where sporting games can be made, where a man has a chance to get away from the crowd now and then, and where he does not continually look against high stone walls being fenced in a narrow dusty yard bare of any shadow, would perhaps be a less fertile soil for plans of that kind to ripen."1

The conditions did drive some men mad. One of the soldiers sent back from the Canadian Expeditionary Force was Ukrainian Yuri Szymko. Being in a highly agitated state, he attacked a sentry and "put his arm through a window." After that, he remained violent and was restrained in the guard room. When his outbursts persisted, he was sent to the hospital and diagnosed with "acute mania."2

There were a number of escape attempts, and some were successful. On Melville Island, ten men escaped almost immediately after being interned there in October of 1914 (the escape was made easier by the fact that the island is not actually an island). A number were recaptured, but some did get away.

At the Citadel, there were five escapes or escape attempts during the years 1915 and 1916. Hans Neu tried the classic approach of dressing like a worker in overalls, picking up some construction materials, and walking out the front door past the guards. It actually worked. The enraged camp commandant had the sentries disciplined.3

One freezing night in January of 1915, nine men chose a moment when one sentry was not on duty covering the rear of the Cavalier Block, which you can now see in front of you. They filed through the window bars, ascended the walls with a homemade ladder, and disappeared into the night. The commandant was once again apoplectic when he received a call from the Halifax Police saying that they had caught two of his prisoners without his guards having even noticed they'd escaped. Two more were later recaptured, but five got away.

In 1916, guards found a ten-foot-long tunnel underneath a bed in the Cavalier Block. The internees had been digging it for many days before it was discovered. When interviewed, half of the prisoners in the camp admitted to working on it.

10. Closure

Notman Studio Nova Scotia Archives 1983-310 number 10198 / negative: O/S N-10198 N-1718

1884

This photo shows the view of Halifax's harbour from the ramparts, a view which was denied to the internees for the duration of their years in captivity here.

From May 1915, the Citadel's internees were all officer-class internees, and therefore merited better treatment and conditions according to the laws of war. The 146 enlisted men (second-class prisoners) were transferred to the new camp in Amherst, Nova Scotia. This left 80 officer-class prisoners in the Citadel (78 Germans and two Austrians) until October of 1916. Finally, as part of a policy to consolidate the camps, those prisoners were also sent to Amherst, and the Halifax Citadel Internment Camp was closed. By that time, the 24 internment facilities across Canada had been reduced to four.

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

2. The Citadel(s)

1. Cornwallis letter 11 September 1749, Internet Archive, online.

4. Seized at Sea

1. Marsters, 18.

2. Marsters, 8.

3. Marsters, 22.

5. Enemy Aliens in the Maritimes

1. Desmond Morton, *Sir William Otter and Internment Operations in Canada during the First World War,* (University of Toronto Press Journals, 1974), 33.

2. Marsters, 6.

3. Marsters, 7.

4. Marsters, 10.

6. The Camp in the Citadel

1. Marsters, 13.

2. Marsters, 13.

3. Marsters, 4.

4. Marsters, 13

5. John Boileau, "Canada and Anti Submarine Warfare in the First World War," *The Canadian Encyclopedia*, October 15, 2021, online.

7. Denounced as Spies

1. Marten, 13.

2. Marsters, 23.

3. Bohdan S. Kordan, *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience,* (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 123.

4. Marsters, 23.

5. Kordan, 123.

8. Isolation

1. Marsters, 30.

2. Marsters, 31.

3. Marsters, 33.

9. Discipline and Escape

1. Marsters, 32.

2. Marsters, 34.

3. Marsters, 35.

Bibliography

Berglund, Abraham. "The War and the World's Mercantile Marine." *The American Economic Review*, Vol. 10, No. 2 (June 1920), pp. 227-258.

Boileau, John. "Canada and Antisumbarine Warfare in the First World War." *The Canadian Encyclopedia*. October 15, 2021. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canada-and-antisubmarine-warfare-in-the-first-world-war

Internet Archive. Cornwallis letter 11 September 1749. https://archive.org/details/selectionsfrompu00nova?view=theater#page/n321/mode/1up

Kordan, Bohdan S. *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience.* Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016.

Kramer, Alan. "Naval Blockade of Germany." *International Encyclopedia of the First World War.* Last updated 22 January 2020. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/naval_blockade_of_germany

Marsters, Roger. "Internment Operations at the Halifax Citadel, 1914-16." *Study for Parks Canada.* Hindsight Historical Consulting, 2014.

Morton, Desmond. *Sir William Otter and Intenrment Operations in Canada during the First World War.* University of Toronto Press Journals, 1974.