Walking Tour

The Challenge of Modernity

Turmoil and Reform 1913-1945

Andrew Farris

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 02-091

When Winnipeg's remarkable period of expansion came to an end in 1912, most believed that this was just a pause in the city's relentless path to prosperity. Few could have conceived the decades of war, civil strife and economic depression that lay ahead.

How would this young and untested society bear up to times of turmoil?

Winnipeggers had little time to adjust to the economic slowdown in 1913 before they found themselves thrust into the greatest and most terrible war the world had ever known. The staggering human and economic cost of the First World War exposed rifts in society that people had had the luxury of ignoring in the good years: The growing gaps between rich and poor, man and woman, British-Ontario elite and everyone else. This was followed by the Great Depression and another, even greater and more terrible war. These hammer-blows, following close on the heels of one another, shook society to its foundations.

In the face of adversity the people of Winnipeg rose to the occasion and emerged stronger from the experience. Overseas, Winnipeg units fought with uncommon distinction in both world wars. At home, the city produced the ideas and leaders that boldly showed all of Canada the way to a more equitable and just society.

The previous era of Winnipeg's history, from 1870 till 1912, is the story of diverse peoples from all over the world coming to this great place to build a metropolis. The next phase of that history is the story of those people coming together to face the challenges of modernity.

This project is a partnership with Heritage Winnipeg. We also owe thanks to the generous support of Travel Manitoba, the Exchange BIZ, and the Fort Garry Hotel.

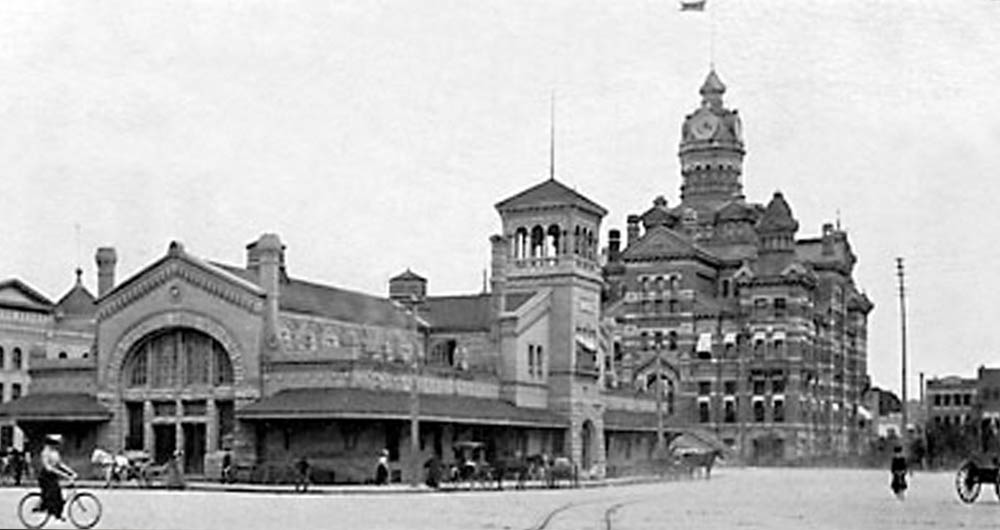

1. The End of an Era

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 02-327

1903

This is the Exchange District at the turn of the last century - at the time, it was the commercial and civic heart of the city. This was a time of relentless growth and prosperity. The belief that the nation stood at the dawn of a Canadian Century was widespread. Such times were not to last. Winnipeg's real estate bubble popped in 1912 and a recession followed.

The explosive economic growth of the previous years had helped paper over the growing inequality in Winnipeg society. When expansion stopped, the promise of future prosperity was not enough to satisfy Winnipeg's poorest citizens. The result was growing unrest.

* * *

By 1912 the signs were there for those who cared to look. Financiers in London grumbled that Canada was overbuilding railways; how could a country with such a tiny population afford three new transcontinentals?

Another ominous sign of the city's future was the rise of new prairie cities to challenge Winnipeg's dominance of the hinterland. Calgary had grown 10-fold in 10 years and it was now sucking up much of the investment that previously went to Winnipeg. In 1912, the CPR quietly began to move large parts of its Winnipeg operations to Calgary. Around the same time, the Port of Vancouver opened up its first grain export terminal -- the Americans finished the construction of the Panama Canal. 2

Finally the clouds of war were gathering in Europe. A war in the Balkans in 1912 shook investor confidence and caused a credit crunch that spread from Europe around the world and into the Canadian West. Banks no longer had money to lend, and began calling in their debts. The real estate bubble collapsed and the new railways started going bankrupt.

"Land booms always collapse when prices become inflated," writes Berton. "But there was more than that behind the slump of 1913. Though few faced up to it, it was the end of an era - an era of free land, wide-open settlement, and easy money."3

2. Fighting for Equality

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 02-297

1903

A woman rides a bike across the street past the old City Market. Behind that is the old City Hall. Bicycles were a potent symbol of female empowerment, giving them a new freedom to move around as they pleased.

During the settling of the West women took on far more prominent roles in the prairie homesteads than they did in the established cities of eastern Canada. Their increased importance argued for their emancipation from the prudish morals of the Victorian era. As the metropolis of the Canadian West, Winnipeg was a hotbed of women's rights activism. The city produced the giant of Canadian history, Nellie McClung, and was the first province to give women the vote.

* * *

However, Winnipeg's women were organizing. E. Cora Hind, a reporter for the Free Press, and Francis Beynon, editor of the Grain Growers Guide, opened people's minds to the inequality around them. Beynon railed against "the tyranny of unrepresentative government and the injustice of debarring any portion of the people from the franchise because of the accident of birth.”1

Their efforts were gaining traction. In 1901 the telephone operators—'Hello Girls'--went on strike against the Dickensian working conditions they were expected to endure. It was the first successful strike action by women in the city.2 Others were to follow.

It was Nellie McClung, an already wildly successful novelist, who rose to lead the fight for their ultimate goal of the right to vote. Having grown up in rural Manitoba, she arrived in Winnipeg in 1911 and formed the Political Equality League. A charismatic speaker with a razor sharp wit, she mocked and satirized the hidebound conservative politicians who denied the suffragists frequent and insistent petitions.

In a public relations masterstroke, McClung and the other suffragists put on a play at Winnipeg's Walker Theatre (located three blocks southwest of here), called the Women's Parliament. It was set in a fictional province where gender roles and rights were reversed. The all-woman parliament held debates about the rights of men to own property, to have joint guardianship of their children, and to vote.

In the play's final act, a delegation of male petitioners approached the female premier (played by McClung). She told the petitioners the same thing the patronizing Conservative premier Richmond Roblin had told her: men were not cut out for the rough and tumble of politics, and their innocence shouldn't be sullied by such rights.

Flipping the script on the men brought the play roars of laughter everywhere it was performed, and revealed the patent absurdity of the conservative position.

As part of their platform in the 1915 election the Liberal Party embraced women's suffrage. McClung and the other suffragists campaigned tirelessly for the Liberals and were crucial in their ultimate victory.

Women's voting rights were passed in the Manitoba Legislative Assembly the next year, setting an example for the rest of Canada. As Berton wrote, "This free wind, blowing out of the West, was soon to have its effect on the entire nation."3

3. The Gilded Age

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 00-032

1901

The Duchess of York disembarks from a carriage in front of City Hall during a royal visit.

While Winnipeg's elites lived in sheltered opulence, the majority of the city's inhabitants struggled to make ends meet. Extreme poverty was rife in the squalid immigrant slums of the North End--'the other side of the tracks.' Many worked dangerous jobs in unventilated factory basements for starvation wages.

Progressive churchmen and reformers, trade unionists, suffragists and temperance advocates all fought to get the concerns of these forgotten people on the political agenda, but their demands fell upon the deaf ears of the business elite. These were the conditions that spawned Canada's most effective labour movement.

* * *

The business and political elites mostly took no interest in the quality of life of those people when they arrived. Tens of thousands of immigrants from eastern and northern Europe were treated as second class citizens and barred from jobs and statuses that were reserved for the Anglo-Saxon elite. The conservative Winnipeg Telegram welcomed a group of Ukrainian and Russian Jewish immigrants to the city by calling them "The scum of Europe."3

Those of British stock reserved for themselves posh neighbourhoods with tree-lined boulevards in the south and west ends, while the rest were crammed into tenement slums in the North End.

Writing for the Free Press, Genevieve Lippett-Skinner visited Barber Street in the North End to see how the other side lived.

"In one rabbit warren of a tenement, when a baby died, the parents kept the corpse for three days before a neighbour phoned the city's health department. In another room, Miss Lippett-Skinner found a young woman whose five-month-old infant was covered with flies; the odour was overpowering. Downstairs she encountered a tear-stained Greek woman living with her family in a single room. Insects had bitten her baby so badly that the child had been hospitalized. The mother's arm was a mass of poisoned bites. For this unfinished room the family paid seven dollars a month."

"In the backyard of this same building, a deserted mother and two children shared a woodshed with rats and other vermin. The father had been gone for more than four months, but the wife refused to move for fear he might return and not be able to find his family."4

In 1912 the infant mortality in the North End was 282 per 1,000, triple the rest of the city.5 That's more than twice as high as the infant mortality rate is in Afghanistan today--the worst in the world--and 56 times higher than today's Manitoba average.6 7

4. The Great War

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 01-029

1915

A parade past City Hall encourages Winnipeggers to invest in war bonds, which allowed the government to maintain the unbelievably heavy financial burden of fighting the First World War.

At the outbreak of war in August 1914, thousands of Winnipeggers enlisted in the army. Given cursory training and shipped off to France, the enthusiastic volunteers soon found themselves locked in a yearslong life and death struggle on the most horrific battlefields in the history of war. Through the crucible of combat they, along with the rest of the Canadian Corps, became some of the most feared and respected soldiers on the Western Front. But the toll was high: some 1,200 Winnipeggers never returned from Flanders Fields.1 The war was the most traumatic event in Winnipeg--and Canadian--history.

* * *

More volunteers followed. By July 1915 Manitoba had raised 18,000 men, organized into 17 battalions. They fought in every engagement with the Canadian Corps. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles alone fought in 23 battles. The places on their honour rolls have become synonymous with horror and death, glory and Canadian pride: the Somme, Hill 60, Passchendaele, Vimy Ridge.

14 Manitobans won the Victoria Cross in the First World War, the British Empire's highest decoration for bravery in the face of the enemy.

In this war conspicuous acts of gallantry were a daily occurrence, and only the most extraordinary feats of heroism would merit consideration for the Victoria Cross. Consider 24-year-old Corporal Leo Clarke of Winnipeg.

In September 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, his unit was tasked with capturing a section of enemy trench. Going over the top and leaving the protection of their lines, they found the German position fiercely defended. Still they continued to close with the enemy, until they came close enough to engage them in bitter hand-to-hand combat, using grenades, bayonets and rifles as clubs. By the time Clarke's section had secured their objective he was the last man left standing: all the other men in his unit had been wounded or killed.

A group of 20 Germans swiftly counter-attacked. Clarke stood alone. He emptied his revolver at the attackers and then picked a rifle off a German body and emptied it into the advancing foe, and then picked up another rifle and did the same. By then he had killed 14 of the 20.

The Germans continued to close in, and an officer leapt into Clarke's trench and bayoneted him in the leg before Clarke shot him dead. In the face of this Canadian berserker, and with all their officers killed, the five survivors began to flee back to the German lines. Clarke cooly took aim with the captured rifle and shot down four of them. The fifth surrendered. Clarke had single-handedly annihilated the counterattack and held the objective.

Actions like this cemented the fearsome military reputation of the Canadians. After the Battle of the Somme, Britain's Prime Minister David Lloyd George said "The Canadians played a part of such distinction that thenceforward they were marked as storm troops…. Whenever the Germans found the Canadian Corps coming into the line, they prepared for the worst."4

When battles lasted for months, the odds of cheating death dwindled by the day. Sadly, Clarke's luck would run out a month later: Defending a newly captured trench, Clarke was buried under a mound of earth thrown up by an exploding shell. His brother Charles frantically dug him out, but the weight had snapped the young corporal's spine. He would die in hospital a week later.

Leo Clarke lived on Pine Street, in a quiet suburb on Winnipeg's west side. Remarkably, by the end of the war two other residents of the street had earned their own Victoria Crosses. Pine Street was renamed Valour Road in their honour.

5. The Powder Keg

1919

The famous image of a streetcar of strikebreakers toppled in front of City Hall during the Winnipeg General Strike. The original photo was taken from an upper-storey window of a building that once existed where you are standing. The general strike was the seminal event in Canadian labour history.

In the late 1910s, soaring inequality, shrinking real wages, and deplorable living conditions, all fomented Winnipeg into a powder keg of popular discontent. The spark was provided when thousands of soldiers returning from the horrors of the Western Front saw conditions had only deteriorated since they departed.

* * *

Wages had barely increased from 1913, though prices had shot up over 60%.1 Since construction in Winnipeg had come to a standstill while the war was fought, there was a massive shortage of housing (one government inspector suspected 10,000 new homes were needed in Winnipeg alone).2 The price of construction materials had skyrocketed, just like everything else, meaning no new homes were forthcoming. Those homes which existed were in disgraceful condition.

The closing down of munitions factories in Winnipeg left the streets filled with unemployed. There was no help coming from the government: like most of the world's governments, it had been pushed to the brink of bankruptcy in the waging of total war.

On the other hand, the business class appeared to be doing just fine. Many had made fortunes selling wheat and munitions to the Allied powers. With most of the world on the verge of economic and agricultural collapse in 1918, the demand for Canadian wheat soared to new heights. None of this wealth trickled down.

Forced back into the slums they thought they'd left in 1914 and reduced to working for a pittance or begging in the streets, the heroes of Vimy Ridge and the 100 Days could tolerate no more.

6. Bloody Saturday

1919

A famous photo of the Winnipeg General Strike taken from a second story window. This was Bloody Saturday, June 21, 1919.

A crowd of strikers 6,000 strong had gathered to hear speeches when a streetcar full of strikebreakers traveled down Main Street. The enraged strikers toppled over the streetcar and set it alight, as seen in the previous photo. Then the "specials," a group of 1,800 deputized officers specially hired by the business elites to crush the strike, and the mounties with them had the pretext they needed to intervene.

Fred Dixon, editor of the Western Labour News wrote, "Then with revolvers drawn, [the Mounted Police] galloped down Main Street, turned, and charged right into the crowd on William Avenue, firing as they charged. One man, standing on the sidewalk, thought the Mounties were firing blank cartridges until a spectator standing beside him dropped with a bullet through his breast ... dismounted red coats lined up ... declaring military control."1

* * *

The vote totals amongst the various unions is illustrative of how much discontent cut across society: "city police voted 149 to 11 for strike action, fire-fighters 149 to 6, water works employees 44 to 9, postal workers 250 to 19, cooks and waiters 278 to 0, and tailors 155 to 13."2

On May 15 the 'Hello Girls' (telephone operators) walked off the job, bringing down Winnipeg's phone system. Within hours Winnipeg had drawn to a standstill: 30,000 workers, virtually the entire working population of the city, had walked off the job. A Central Strike Committee was formed from representatives of all the unions and, for the rest of May and into June, became the effective government of Winnipeg.

The business elite recognized the threat and feared a Bolshevik Revolution like the one that had just toppled the Russian Czar. They formed the "Citizens' Committee of One Thousand," and demanded that the City government fire the entire police force, who had voted in favour of the strike and now refused to disperse it. The City, firmly siding with the business elite, obliged. The Committee then paid out of their own pocket to create a new force of 'special police.' Though untrained, the specials were paid better than the regular police to ensure their loyalty, and armed with baseball bats and revolvers.

As the weeks wore on and sympathy strikes broke out across Canada, the federal government became worried and three cabinet members came to Winnipeg to meet with the Citizens Committee and the municipal government. Tellingly, the cabinet ministers refused to meet the strike leaders.

After these one-sided consultations the federal government apparently decided it had heard enough. They began aggressively demanding that the strikers return to work and dispatched mounties as reinforcements for the Committee's specials. Then they had ten of the labour leaders arrested.

The crowd gathered on Main Street on June 21, 1919, to protest the arrest of the strike leaders. That was when the specials charged into the crowd. As the crowd of strikers dispersed into side streets they were met by more specials who ruthlessly beat them with bats. Two strikers were killed by gunshot wounds and around 35 injured.3

By the end of the day the army had entered the city and was patrolling the streets with machine guns mounted on trucks. The specials shut down the Western Labour News and arrested the editors. Winnipeg was a city now under military occupation.

Fearing a bloodbath, the Central Strike Committee called off the strike on June 25, 1919.

7. Canadian Social Democracy

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 05-001

1880s

Police pose outside the station around the turn of the century.

The crushing of the strike demoralized workers across the country. The strike's leaders were put on trial and some sentenced to jail terms of up to two years. It was the last attempt at a major general strike in Canada during the 1920s. A recession soon led to high unemployment that further undermined labour's bargaining power.

One silver lining for the struggling workers was that the strike catapulted the Methodist minister James Shaver Woodsworth into the national spotlight.

* * *

"I fear that in our city we have not yet learned the vulgarity of a lavish expenditure of newly acquired wealth. Costly dresses, magnificent houses, expensive entertainments - those are the things we seek after. And the snobbishness that goes with such vulgarity! The pride of wealth…"1

One imagines the audience reception to these words was cold. By 1904 he had grown disillusioned with the apathy of the rich and began tending to the souls of the immigrants in the slums himself. Over the years he developed a strong set of social democratic principles.

15 years later during the General Strike he was a prominent voice for the workers. This led to his arrest, though he was later released. With that he became a nationally known public figure and was elected to Parliament to represent Winnipeg's North End. He was an active parliamentarian and was instrumental in getting Canada's first old age pension passed in 1928.

Later Woodsworth helped form a new national social democratic party: the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), and became its first leader. This party would form the embryo of the New Democratic Party (NDP), formed in 1961, which remains one of Canada's major parties today.

As the Canadian Encyclopedia writes, "Although the CCF had never held power nationally, the adoption of many of its ideas by ruling parties contributed greatly to the development of the Canadian welfare state."2.

For that Canadians have Winnipeg's J.S. Woodsworth to thank.

8. Change and Identity

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 08-007

1910s

A group proudly pose with their new cars in front of the Leland Hotel, which was considered one of the poshest in the city. At the time this photo was taken cars were a luxury restricted to the privileged few. By the 1920s, however, mass production techniques had brought cars within reach of the middle classes. Car owners called for the paving of roads, and the cars came to dominate the roads themselves, which were previously more of a public space. New technologies were transforming society in ways few could have foreseen.

* * *

A related invention, the combine harvester, also meant that far fewer farm labourers were necessary to bring in the prairie harvest. As railway building wound down there were also far fewer jobs to be had in construction. This meant the shift in population from the countryside towards the cities began to accelerate. In 1901, 72% of Manitoba's population lived in rural areas. By 1931 this had declined to 55%, with the 45% of urbanites overwhelmingly concentrated in Winnipeg. By 1971 the transition was complete: fully 70% of Manitobans now lived in urban and suburban areas, a ratio that has stayed steady to the present.1

In Winnipeg in the 1920s the young people flocked to the exciting new picture shows. These connected Winnipeggers to the increasingly dominant American Hollywood culture, and spelled doom for the city's vibrant theatre scene. Many of the once popular theatres and vaudeville houses couldn't compete and shut their doors, leaving a gap in the city's cultural fabric that has been difficult to fill to this day.

The influx of American cultural influences did not prevent the formation of a distinct Manitoban identity. The shared experience of the First World War, key to the emerging Canadian identity, also brought Manitobans together and made them aware of their common experience.

By 1930 most of the city's inhabitants were still close enough to their roots to be easily identifiable. As W.L. Morton writes, "The mark of the Scot, of the Irish, Welsh, or Englishman was still discernible even when blended; the descendant of Red River stock was almost as sure to betray his background as the Polish or German Canadian."

Nevertheless, a concrete Manitoba identity was beginning to coalesce around some broad characteristics imported by the British and Ontario immigrants who then dominated society's elite:

"In manners, speech, and outlook it was this group which was the formative force in provincial society. Their direct manners, clipped, flat speech, and concern with material success overlaying an ancestral concern with moral values, gave Manitoban life its tone. The prevailing outlook and way of life were still rural, simple, and unpretentious. Even that central core of Winnipeg, the Winnipeggers who were such by settlement and descent, were only a suaver version of the rural people, with whom their ties by blood and business were intimate. Even on [wealthy] Wellington Crescent, Manitoban life was essentially unsophisticated."2

9. Depression

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 04-253

1923

This dramatic photos shows fire crews combating a blaze in the upper storeys of an Albert Street office building.

The Canadian economy struggled through the 1920s. Following a major recession that lasted until 1924, there was a period of modest growth, but it was muted. As one historian puts it, the 20s "did not roar in Canada."1

This meant that when the effects Great Depression rippled across the globe, Manitoba was ill prepared to cope. Winnipeggers suffered mightily as banks collapsed, businesses shuttered, and unemployment shot up by 30%.2 Tax revenues collapsed and the Conservative federal government's insistence on balanced budgets meant there was little aid forthcoming from Ottawa.

* * *

In Manitoba the pain first made itself felt with the collapse in the grain markets, the city's economic lifeblood. As depression spread throughout the world, governments enacted protectionist policies to prevent the outflow of money. Demand for wheat fell off a cliff andhe price of wheat went with it, with it reaching a record low $0.34 a bushel in 1932.4 Prolonged years of drought caused dust bowl conditions, and farmers watched helplessly as millions of tonnes of top soil literally blew away.

The depression's effects began to ripple across the prairie economy. The railways, some of Winnipeg's largest employers, began laying off thousands of workers. Construction of all kinds ground to a halt. Construction of the Richardson Building, a 17-storey skyscraper topped with a giant clock tower, had begun at the north-east corner of Portage and Main in the summer of 1929. Financing dried up and construction halted temporarily, and then permanently. The huge construction site would lie abandoned for years. Eventually it was turned into a gas station.

Thousands of farm labourers and railway workers were flooding into Winnipeg seeking public relief. They thronged Market Square and marched on the Legislative Assembly, demanding government action.

The municipal government had paid out $26,000 for unemployment relief in 1929. This ballooned to $1.3 million in 1933, and that was only the one-third municipal government share of the total.5 Because tax revenues had collapsed, this put a massive strain on the public finances.

"They were bitter years," writes the historian W.L. Morton. "As worklessness became the accustomed mode of life of the unemployed, as every freight train had its row of transient unemployed, as the fires gleamed nightly in the 'jungles' where the wandering workless lived before moving on. On the farms the equipment grew older year by year, houses and barns more weatherbeaten; the 'Bennett buggy' [named for the Conservative prime minister] appeared, an old car horse-drawn; the towns became more rundown year by year as the dust from the blowing fields swirled down their empty streets."6

The worst year of the Depression was 1933, but the remainder of the thirties would be a time of sharply reduced expectations. By 1939, the tepid recovery had begun to gather steam and a return to normal life seemed on the horizon. However, the brewing war in Europe and Asia called Winnipeggers to endure the final ordeal of this tumultuous time.

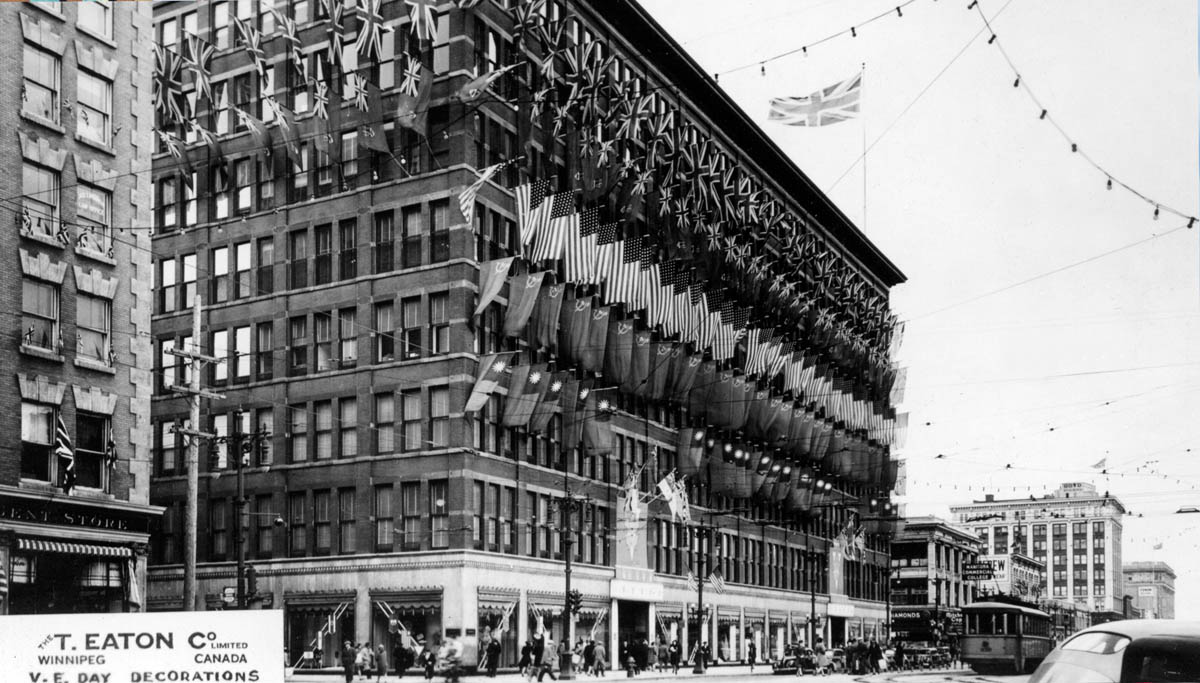

10. The Second World War

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 04-138

1945

Decorations and bunting have been put up across the Eaton's Department Store on Portage Ave. They are celebrating the end of the war in Europe, the major part of the biggest war in history.

* * *

When the troops came home, things were different from 1918. The economy was booming and activist government policies worked to reintegrate the soldiers in civilian life. Winnipeg was entering a new era of post-war peace and prosperity.

It is fitting to end this tour on Portage Ave. Though the Exchange District was Winnipeg's first business district, large companies like Eaton's had been shifting to Portage Ave for decades. By 1945 that shift in power was complete, and the Exchange District became a relatively quiet warehouse district. It is only in the last 20 years that the Exchange has revived as a trendy tourist and shopping district, regaining some of its old glory.

Endnotes

1. The End of an Era

1. Pierre Berton. The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914. (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1984), 326.

2. Ruben Bellan. Winnipeg's First Century: An Economic History. (Toronto: Queenston House Publishing, 1978), 110.

3. Berton, 341.

2. Fighting for Equality

1. "Francis Marion Beynon," The Canadian Encyclopedia. Accessed May 20, 2018.

2. Christopher Dafoe, Winnipeg: Heart of the Continent. (Winnipeg: Great Plains Publications, 1998), 108.

3. Berton, 309.

3. The Gilded Age

1. Berton, 290.

2. Berton, 290.

3. Dafoe, 91.

4. Berton, 294.

5. Dafoe, 108.

6. "Infant Mortality Rates," CIA World Factbook. Accessed May 23, 2018.

7. "Annual Statistics 2015-16," Government of Manitoba, 19.

4. The Great War

1. P. Cain and L. Schroeder. "Mapping Winnipeg's First World War Dead." Global News. Nov. 8, 2013.

2. W.L. Morton, Manitoba: A History. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1957), 340.

3. Morton, 357.

4. Arthur Bishop, "Valour On The Somme: Part 5 of 18." Legion Magazine. Sept. 1, 2004.

5. The Powder Keg

1. "The Winnipeg General Strike", CBC News.

2. Ruben Bellan. Winnipeg's First Century: An Economic History. (Toronto: Queenston House Publishing, 1978), 138.

6. Bloody Saturday

1. CBC News.

2. "Labour's Revolt," Canadian Museum of History.

3. Canadian Museum of History.

7. Canadian Social Democracy

1. Berton, 302.

2. Alan Whitehorn. "Co-operative Commonwealth Federation", The Canadian Encyclopedia.

8. Change and Identity

1. "Population, urban and rural by province and territory (Manitoba)", Statistics Canada.

2. Morton, 408.

9. Depression

1.Christopher Dafoe, Winnipeg: Heart of the Continent. (Winnipeg: Great Plains Publications, 1998), 137.

2. Bellan, 205.

3. Morton, 421.

4. Morton, 422.

Bibliography

Bellan, Ruben. Winnipeg's First Century: An Economic History. Toronto: Queenston House Publishing, 1978.

Berton, Pierre. The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1984.

Bishop, Arthur. "Valour On The Somme: Part 5 of 18," Legion Magazine. Sept. 1, 2004. Accessed May 25, 2018.

Cain, P. & Schroeder, L. "Mapping Winnipeg's First World War Dead." Global News. Nov. 8, 2013. Online. Accessed May 22, 2018.

CBC News. "The Winnipeg General Strike." Online. Accessed May 22, 2018.

Canadian Museum of History. "Labour's Revolt." Online. Accessed May 22, 2018.

CIA World Factbook. "Infant Mortality Rates." Online. Accessed May 23, 2018.

Dafoe, Christopher. Winnipeg: Heart of the Continent. Winnipeg: Great Plains Publications, 1998.

Government of Manitoba. "Annual Statistics 2015-16." Online. Accessed May 22, 2018.

Morton, W.L. Manitoba: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1957.

Statistics Canada. "Population, urban and rural by province and territory (Manitoba)." Online. Accessed May 25, 2018.

The Canadian Encyclopedia. "Francis Marion Beynon." Online. Accessed May 20, 2018.

Whitehorn, Alan. "Co-operative Commonwealth Federation", The Canadian Encyclopedia. Online. Accessed May 22, 2018.