Walking Tour

Stonewall's Main Street

The Tale of a Town

Andrew Farris, Elyse Abma

Since its founding in 1880, Stonewall has transformed from a collection of homesteads into a successful town with a rich history. In this tour, we will take a stroll down Main Street and learn about how Stonewall was founded, what drew people here, and what it was like to grow up in the first few decades of Stonewall.

This project is a partnership with the Town of Stonewall.

1. The Founding of Stonewall

Stonewall: Turning a Century, Plate 32

ca. 1900s

A wintry view of Stonewall's Main Street, or Jackson Avenue, as it was once called. The former name of Stonewall's most important street tells the story of the man who was the driving force for the establishment of this community.

Samuel Jacob Jackson was certainly not the first person to come to the place we now call Stonewall, but it was his vision and planning that led to the development of this patch of land into a town that quickly prospered.

As Stonewall's centennial books says, "It was through Mr. Jackson's ingenuity, enterprise and energy that the townsite was developed, and to him Stonewall owes its beginning. He associated himself with many of the businesses in town, and through financial and personal help, encouraged commerce to begin and develop."1

* * *

By 1875, at only 27 years old, Jackson had saved up enough money to begin buying land. Hearing rumours about a planned railway spur north of Winnipeg, he bought up a large plot of land near the planned route. He had grand dreams to turn that land into a prosperous prairie town.

Over the next few years, Jackson lived and worked in Winnipeg while refining plans for his little town. With offers of free land and money he enticed a few homesteaders and several businessmen who opened up a steam grist mill. Jackson, for his part, continued working in Winnipeg and also won election as city alderman.

In 1880, the railway finally reached Winnipeg, and the long-expected spur line to the north was expected to soon follow. Jackson was ready and put his plans into action, having the townsite surveyed with streets (named after his friends and family), and subdivided into lots for sale.

What was the town to be called? It's not known how Stonewall got its name, but there are many stories. The most popular story is that Jackson had earned the nickname 'Stonewall', after the famous Confederate general Stonewall Jackson, who was killed at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. Stonewall fit Jackson because "although short in stature, he was a man of straight military bearing," writes the town's Centennial book. "And it is said that he considered the name an honor and so named the town."2 The rocky ridge of limestone on the north and eastern sides of town might also have played a part.

With a railway soon to follow, the newly christened Stonewall was well placed to capitalize on Western Canada's economic boom.

2. Main Street

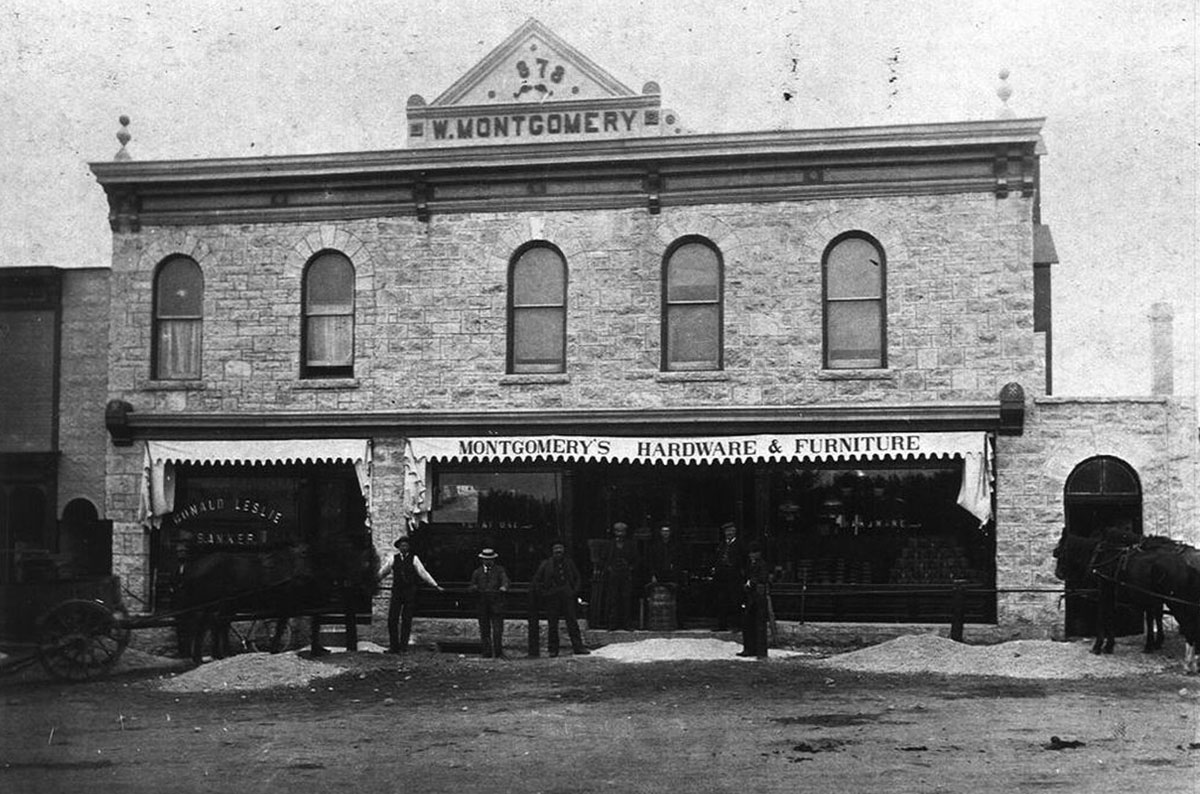

Stonewall: Turning a Century, Plate 13

ca. 1890s

A group of men pose for a photo in front of the new building housing Montgomery's Hardware & Furniture. You can see the date 1878 (short a 1) on the building's peak, showing this is one of the oldest buildings in Stonewall, built a couple years before it became Stonewall.

John Montgomery started out as a blacksmith, a crucial role in the community in the days of horse and buggies (one of which can be seen in this photo) and when pioneers were setting up farms and quarries. His business was originally on the other side of the road, behind where you're currently standing. In 1884, he changed it to a hardware and furniture store and kept running it until his death in 1889. His son Weston took over, and in the 1890s he bought the building you're looking at now and moved Montgomery's into it.

Since then, the building has been heavily renovated, but the window layout on the first floor and the single storey adjoining section on the right remind us of its earlier appearance.

* * *

The quarriers needed tools and equipment, as well as all the necessities of life. Initially they had to make the trip to Winnipeg to get these goods (some apparently walked there on occasion), but soon all sorts of businesses began to spring up in Stonewall to service their needs. Farmers from the surrounding areas also started coming into Stonewall to buy and sell.

By 1884, Stonewall could boast "a planing mill, four hotels, two butchers, four grocers, a drug store, two blacksmiths, five lime kilns, baker, barber, watchmaker and jeweler, boot and shoe shop, harness shop, bellows factory, millinery, grist mill, a weekly newspaper, a hardware and tin shop, and two grain buyers."2

Both sides of Main Street were filled with businesses, and a lively town had come into being.

3. Trappings of a Town

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives

ca. 1920s

Now you are looking at Stonewall’s post office, which was built in 1914 and designed by Francis C. Sullivan, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright. This post office, intended to be a prototype for post offices across the prairies, was the only one built. To this day, it is studied by architectural students, who admire its "combination of smooth-cut and hammer dressed limestone, and deep-set windows."1 Behind it is an elevator built in 1899 on the property of the early steam grist mill set up in 1877.

In the decades that followed Stonewall's founding, the town grew and attracted many of the trappings of a town, like this post office. Numerous schools and churches were also built, while members of the community banded together to form an array of clubs, sports teams, and charities, ensuring there was never a shortage of things going on in the community.

* * *

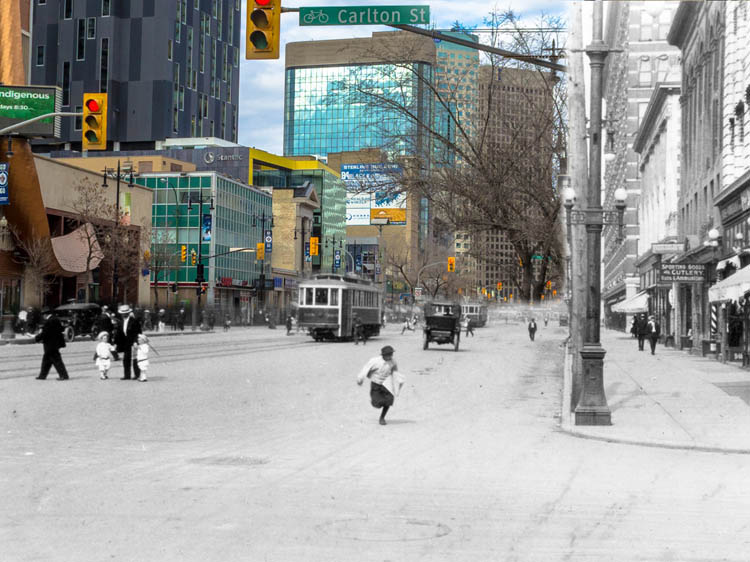

An electric railway was built in 1914, offering commuter service to Winnipeg until it was supplanted by buses in 1939. Telephone and electrical lines were laid around this time, giving people access to the modern conveniences we take for granted today. That new fangled invention, the 'car', was met with great enthusiasm in Stonewall, and in 1909 a local Auto Club was formed, the first in Western Canada.

Fraternal organizations like the Masons, Oddfellows, and Kinsmen Club gave Stonewall's inhabitants places to socialize outside of work and church, and acted to advance many charitable initiatives throughout the community. Sports were also incredibly popular. Football games drew huge crowds in the summer, while over the long winters men and women could join Stonewall's hockey, curling, and snowshoe clubs.

4. A Cause for Decoration

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives

1918

The building on the left started life as Alfred Ashdown Hardware in 1882. It has since gone through several name changes (at the time of this historic photo it was Walter Seed Hardware), but the building more or less survives, albeit in heavily renovated form. Notice the same limestone wall on the right side.

The grand building across the street at the right is the Town Hall. Made from Stonewall limestone and completed in 1912, the hall housed the community's municipal offices, local government chambers, and has also frequently been used for public events like dances, graduations and movie screenings. In this photo it's decked out in British Empire flags and has a banner saying "Welcome Home," indicating this photo was probably taken in 1918 or 1919 when the Stonewall men who fought in the First World War were returning home.

There are many photos showing Main Street decked out with flags and pennants, from patriotic displays during wartime, to the occasion of births, marriages, and deaths in Britain's royal family, and also on festive occasions such as Labour Day and the annual Rockwood County agricultural fair.

* * *

“A reporter this morning conversed with a gentleman, who attended yesterday the annual Rockwood fair at Stonewall. He gave an amusing account of the trouble occasioned by some of the Judges, who foolishly consented to act in award of the prizes for the baby show. As every one knows this is a thankless position at best, and when as is generally the case one or more irate mothers give vent to their disappointed hopes, it becomes one simply of unbearable torture. The decisions rendered by the Stonewall judges affected a well-known lady of this city, who expressly journeyed to the scene, with the brightest prospects imaginable of securing with her darling baby, the first prize, affording herself the opportunity of enjoying the disappointment of her discomfited rivals. It was not to be however, and the poor judges found out to their sorrow that a vexed woman's tongue removes all the pleasure derived from a consciousness of having done their duty to the best of their ability.” 2

Today the main fair held in Stonewall are the Quarry Days, which take over the town for three days every August. Fortunately, the cute baby competition is no longer included.

5. Stonewall's Victoria Cross

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives 367

ca. 1900s

In front of you is a rather unassuming house in downtown Stonewall. Nowadays, it is the McLeod Tea House, but over a century ago it was the home of Alexander Neil McLeod, the town doctor; and at one point, the mayor. His wife, Margaret Arnett McLeod, became a distinguished Canadian historian. However, their son, Alan would eclipse both of them in the history books.

Alan Arnett McLeod was born in 1899 and grew up in that house. In 1917, as soon as he turned 18, he joined the Royal Flying Corps, hoping he could make it to France to catch the tail end of the First World War. He was not to be disappointed.

Flying an artillery spotter plane over the Western Front in the spring of 1918, McLeod's plane was set upon by eight colourful German Triplanes from Manfred von Richtofen--the Red Baron's--elite 'Flying Circus'. What followed was a truly astonishing feat of flying and bravery as McLeod desperately fought to put the plane down and save the life of his crewmate. In honour of his heroism, he was awarded the Victoria Cross, the British Empire's highest award for bravery. At 18, he remains the youngest Canadian ever to receive this distinction.

* * *

Within months, he was commissioned as an officer and assigned to a squadron flying lumbering two-seater Whitworth F.K. 8 biplanes. "They're some bus," McLeod said of the plane in a letter home. "I'd much rather fly a smaller machine, they are easier to stunt with."

Despite being denied the opportunity to fly the more agile and glamorous fighters, the tall, lanky youth was still able to showcase his flying skills in the big planes. "I looped one the other day. I was the second person here to do it, they're perfectly safe but people didn't know it."

Their squadron was dispatched to France in late 1917 and assigned missions like reconnaissance, artillery spotting, and tactical air support. Until the next spring, McLeod and his observer Lieutenant Arthur Hammond carried out a number of these fairly straightforward missions, flying back and forth over the trenches. On one mission, they shot down a German scout plane, and a few days later they shot down another scout and an artillery balloon. Still, in his letters home McLeod insisted his job was a safe one: "Just to let you know how safe I am I'll tell you that the Squadron I'm in has only had 1 man killed in the last 6 months and he killed himself by doing a fool trick with his machine."

Then on March 21, 1918 all hell was let loose. The Germans had been secretly planning a massive final war-winning offensive, and caught the Allies completely by surprise. German stormtroopers surged forward, taking ground in days that took the Allies four years of ghastly trench-warfare to seize. Hundreds of German planes, held in reserve for this moment, were unleashed over the front, sweeping the skies clear of Allied aircraft.

On March 27, McLeod was trying to hold back the German tide, bombing and strafing advancing troops, when they spotted a Fokker tri-plane and shot it down. In moments they were set upon by seven more Fokkers, all painted crazy colours and patterns to indicate they were part of Manfred von Richtofen's Flying Circus. These were the best airmen in the German Air Force. As McLeod dodged and weaved through the swarm, Hammond in the back seat used his swivel machine gun to shoot another Fokker down.

McLeod's cumbersome F.K. 8 was outmatched and within seconds it had been hit in multiple places. Both McLeod and Hammond were grievously wounded. The bottom of the cockpit had been shot out so Hammond had to practically climb out of the cockpit to keep operating the machine gun. Another bullet had penetrated the fuel tank located in the engine and set it on fire, sending flames shooting towards McLeod. They did not have parachutes (they were thought to encourage cowardice) so the only way to survive was to safely land the plane.

Still dodging the swarm of Fokkers, McLeod climbed out onto the wing and reached into the cockpit to grab the controls and guide the plane down. Somehow, McLeod succeeded, crash landing in no man's land in the middle of a battle. Immediately, McLeod went to aid Hammond, who had been hit six times and thrown from the plane. While being fired upon by German machine guns, McLeod fearlessly tried to carry him to the lines of a nearby South African unit. However, McLeod had been hit five times that day, once while moving Hammond, and could only roll Hammand towards the South Africans. After what felt like an eternity, they made it to the safety of their own trenches and both were evacuated to hospitals in England.

When the people of Stonewall heard what Alan McLeod did, they were thrilled. His father sailed to England to be at his son’s side while he recovered. By September, he was healthy enough to travel home. However, he was still weak from the long recovery and within weeks, he had contracted influenza and became yet another victim of the 1918 pandemic a few days later.1

6. Into the Future

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives

ca. 1920s

Two women look out the back of their convertible in front of the Town Office. Throughout its early history, Stonewall moved by starts and leaps - they had the exciting growth from the 1880s to the 1910s, then it was brought to a standstill by the First World War and the Great Depression. Following that was yet another World War, then there was the postwar economic expansion accompanied by advances in technology, and then the end of Stonewalls limestone era came in the 1960s.

Since then, Stonewall has continued to steadily grow, well beyond what people might have expected after the quarries shut down. In 1951, the population was only about 1,000, but today it is almost five times as large and continues to grow steadily. There's no reason that this resilient town won't continue to weather whatever challenges lie in the future.

Endnotes

1. The Founding of Stonewall

1. Mervin E. Farmer, Stonewall: Turning a Century 1878-1978, (Stonewall: Interlake Publishing Ltd, 1978), 11.

2. Farmer, 12.

2. Main Street

1. Farmer, 13.

2. Farmer, 13.

3. Trappings of a Town

1. Farmer, 61.

4. A Cause for Decoration

1. The Brandon Mail, "Provincial," October 4, 1883, online.

5. Stonewall's Victoria Cross

1. Carl A. Christie, "The Forgotten Victoria Cross: Alan Arnett McLeod." Vintage News, online.

Bibliography

Christie, Carl A. "The Forgotten Victoria Cross: Alan Arnett McLeod." Vintage News. http://www.vintagewings.ca/VintageNews/Stories/tabid/116/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/27/The-Boy-Hero--Alan-McLeod.aspx

Farmer, Mervin E. Stonewall: Turning a Century 1878-1978. Stonewall: Interlake Publishing Ltd, 1978.

The Brandon Mail, "Provincial," October 4, 1883, online. www.peel.library.ualberta.ca